Why does the UK need China to build its nuclear plants?

- Published

The UK's Hinkley Point nuclear power station has major backing from China. But why does the government need their help?

It will be the first nuclear plant in the UK for 20 years. Hinkley Point C in Somerset is expected to provide up to 7% of the UK's electricity needs and create thousands of jobs.

The project by French energy company EDF is going to be partly backed by China through a £2bn deal that the government has said it will guarantee.

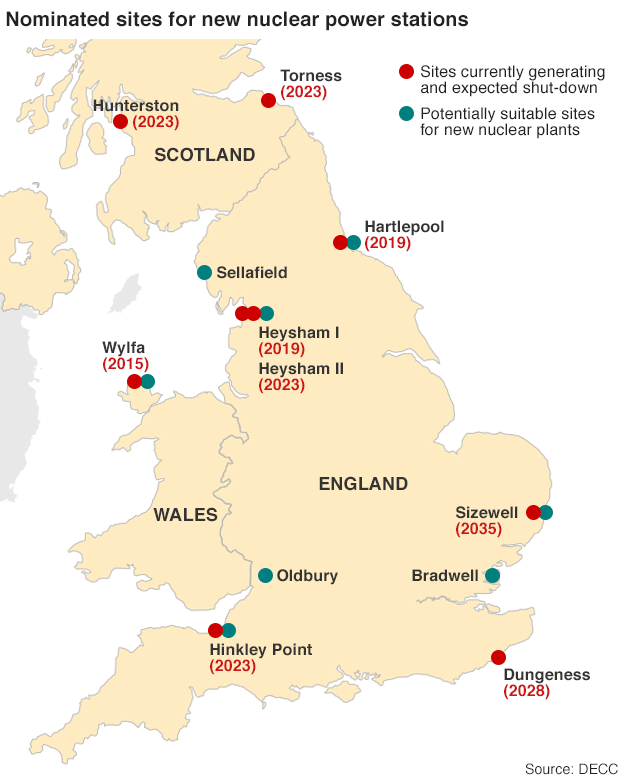

Chancellor George Osborne has said that will allow "unprecedented co-operation" on the construction of more nuclear plants. There are already reports that a Chinese-designed nuclear reactor could be built in Essex.

But the UK used to be a leader in the nuclear energy industry. It opened the world's first civil nuclear reactor in the 1950s, external. So why does a country with so much experience now need help from abroad?

"Nuclear power plants are astonishingly expensive," says Stephen Thomas, energy policy expert and a retired professor from the University of Greenwich Business School.

Constructing a large nuclear reactor takes thousands of workers and needs a huge number of components and materials, external. The site needs to be prepared beforehand and a whole host of systems put in place from cooling to back-up safety mechanisms.

The cost of construction alone at Hinkley Point is estimated at a massive £24bn, external. Few private companies are able to afford that kind of money.

It's also difficult to put a price tag on projects because of the uncertainties in how long construction will take, explains David Toke, energy politics reader at the University of Aberdeen. "You don't really know what the costs are going to be before you start building," he says.

There are also technology risks. "Most of the time it doesn't get built on time, it doesn't get built to cost and it doesn't always work as well as it should do," explains Thomas.

Hinkley in particular is going to use a reactor design that has raised a few eyebrows among its critics. It will use European Pressurised Reactors (EPR). "The two [plants] of this design that are being built in Europe are badly behind schedule and over budget," says Richard Green, professor of sustainable energy business at Imperial College London.

The new nuclear plant

£24.5bn

estimated cost of new nuclear plant at Hinkley Point

-

19% UK's electricity needs currently supplied by nuclear power

-

7% of Britain's electricity needs will be supplied by new Hinkley plant from 2023

-

£2bn sum guaranteed by the UK for the new plant

The reactor has also run into problems with safety regulators in France after a flaw was found in the steel housing the reactor core.

These issues are not reassuring for a potential investor or for a bank considering a loan to a developer.

Some people argue that the government could avoid this by investing straight into Hinkley, using its ability to borrow long-term funds at a low rate. "I believe that if the UK government has confidence in the project it could and should invest directly - it would be cheaper to do that than paying to borrow money from the Chinese," argues Nick Butler, an economist and visiting professor at Kings College London.

But the UK is unlikely to want to be seen to be borrowing vast sums of money, says Green. Involving the private sector avoids the risk of the government having to pay a big sum up-front. It's a similar logic to that behind Private Finance Initiatives (PFI). A PFI is a way of funding a large public infrastructure project such as a new hospital through private sector companies who will build it, operate it and then lease it back.

The government makes PFI repayments over a long period of time and the debt does not become part of the deficit balance sheet. "The British government is determined to get the deficit down," argues Stephen Tindale, director of the Alvin Weinberg Foundation that campaigns for next-generation nuclear reactors. "The politics of deficit reduction and the government's failure to distinguish between capital investment and ongoing expenditure means that they have not taken this route."

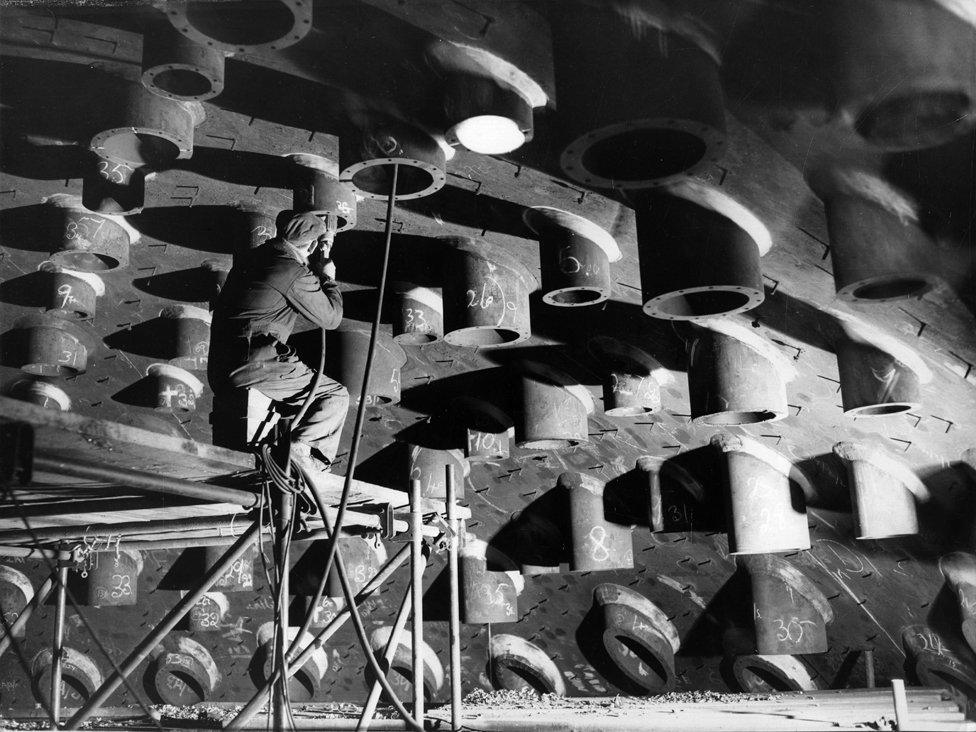

Control nozzles on Hinkley Point A nuclear power station, now retired, photographed in 1961

But Green argues that a reluctance to invest directly in the Hinkley project could be a legacy of past problems. "The state did in many ways make quite a mess of running things through the 60s and 70s," he says.

The government says that it's sensible to attract foreign investors because it avoids committing billions of taxpayers money into the power stations, allowing it to be used elsewhere. "Money I would otherwise be able to spend on the health service or the education system or indeed give lower taxes to people," said Osborne.

The UK has turned to state-backed foreign companies such as EDF to fund the next generation of nuclear plants. But even EDF cannot afford the full costs of a project as big as Hinkley Point C.

As the world's biggest builder of nuclear power stations, Chinese state-owned companies are obvious candidates, external. The country currently operates 24 nuclear reactors with a further 25 under construction.

A deal with the UK could work well for China, explains Thomas, because the country wants to export its nuclear technology to the West. A mostly Chinese-owned plant in Bradwell would be a juicy incentive.

"If their design is good enough for Britain, and passes the British regulators' requirements, that would be a huge marketing coup for them," he says.

Chinese investment in UK nuclear power stations would also bring expertise with it. China has a track record of delivering power plants on budget and on time, external. The Chinese nuclear industry has a lot of skills that would be of use to the UK, explains Peter Haslam, Head of Policy at the Nuclear Industry Association.

"We would expect parts of the UK supply chain to be heavily involved in future Chinese projects," he says, adding that a "partnership" with China makes sense in a nuclear market that has become truly international.

A desire to become a good friend to the world's second biggest economy might also be playing a role. Osborne has not made it much of a secret. "My message is clear," he said this week. "Britain and China - we'll stick together.", external

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.