Viewpoint: Islamophobia has a long history in the US

- Published

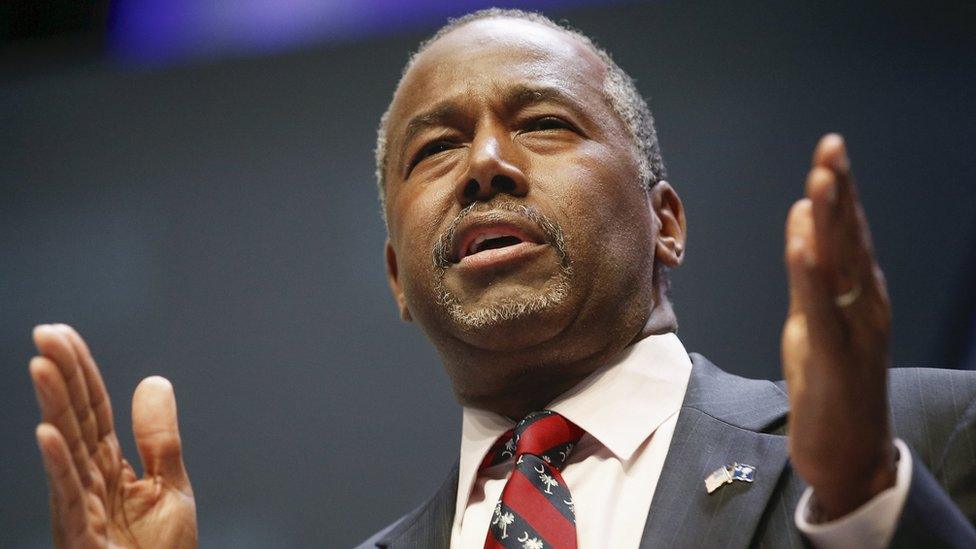

Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson's comments on Muslims in US political life made headlines, but scholar Khaled Beydoun says such comments don't happen in a vacuum - but rather are rooted in a legal tradition of suspicion towards Muslims.

Earlier this month, Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson told US media he would "not advocate that we put a Muslim in charge of this nation," in response to a question about whether "Islam is consistent with the Constitution".

Carson's statement galvanised defenders on the extreme right and prompted critical responses spanning from scorn to constitutional critique.

But Carson's statement was neither an isolated nor novel attitude. In June, a poll by Gallup found 38% of Americans would not vote for a "well-qualified" Muslim presidential candidate.

The root of his comments are found both in America's legal history and today's policing of Muslim communities.

"Islamophobia" is what it's called today. But the rising fear, hate and discrimination that currently threatens eight million Muslim Americans stems from a long and established American tradition of branding Islam as un-American, and demonising Muslim bodies as threat.

Ben Carson has been under fire for statements about Islam

Denied citizenship

On the morning of 19 April 1995, the Federal Building in Oklahoma City was rocked by a bomb. The domestic terrorist attack killed 168 people and injured 680 more. Minutes after, media reports speculated that "Islamic extremists" or "Arab radicals" were the culprits.

Ninety minutes after the explosions, Timothy McVeigh - a white, Christian male - was arrested and later linked to the attack. There had been no evidence to support the idea Muslims had anything to do with the bombing.

Despite people with similar ideologies to McVeigh were responsible for the majority of domestic terrorist attacks in 1995 - a figure still true today - the legislation that followed the Oklahoma city bombing did not place its focus there.

The Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA) was the beginning of policing of Muslim subjects and communities. One part of this legislation led to the disparate investigation of Muslim American political and social activity, while another led to the deportation of Muslims with links - real or fictive - to terrorist activity.

This policing was broadened and intensified after the 9/11 terrorists attacks. More recently, US Homeland Security's Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) programme, as well as political demagoguery, further expands the suspicious focus on Muslims.

Muslims take part in Eid al-Fitr celebrations this year in Brooklyn

Until 1944, American courts used Muslim identity as grounds to deny citizenship. Even Christians perceived to be Muslims or feared to be "of mixed Muslim ancestry" were denied.

One Supreme Court ruling discussed the "[t]he intense hostility of the people of Moslem faith [toward Christian civilization]". Other courts issued rulings based upon the idea there was an inherent menace and threat to American life", external posed by Muslims and Islam.

The courts looked beyond the genuine contours of Islam as faith, and mutated it into a political ideology, and most saliently, a homogenous race - instead of a multi-ethnic and multi-racial religion.

Residents protest a teacher accused of using an ethnic slur against a Muslim student in Florida

From 1790 until 1952 whiteness was a legal prerequisite for naturalised American citizenship. And Islam was viewed as irreconcilable with whiteness.

In a 1913 decision called Ex Parte Mohreiz, the court denied a Lebanese Christian immigrant citizenship because they associated his "dark walnut skin" with "Mohammedanism".

And in 1942, a Muslim immigrant from Yemen was denied citizenship because, writing about "Arabs" the court noted: "it cannot be expected that as a class they would readily intermarry with our population and be assimilated into our civilization."

In this case, the court conflated "Arab" with "Muslim" identity. The courts too believed that such an identity was "inconsistent with the Constitution", and said so in public rulings.

These legal baselines, rooted in old case law, are part of the rhetoric used by both Mr Carson and Donald Trump. But they also form the foundation of a current breed of state-sponsored Islamophobia.

The 'logic' of targeted policing

Fear of Islam is tightly knit into the American fabric, and deeply rooted in its legal, political and popular imagination. Whenever a domestic terrorist attack takes place in America, many quickly turn to tropes of an "Islamic menace" or "violent foreigner, external". While these tropes have taken on new forms and frames, they are conceptually identical to their predecessors.

Where evidence is lacking, both political rhetoric and national security policing apparatuses will justify their scrutiny of Muslims by using these tropes.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, or more recently, the Boston bombings (which spawned CVE policing), proponents of state-sponsored Islamophobia will justify disproportionate policing of Muslim Americans and the communities they live in on the grounds of isolated attacks involving Muslim culprits.

Although Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) statistics show that only 5% of domestic terrorist attacks involve a Muslim culprit, CVE is a programme functionally tailored to prevent and police Muslim Americans.

Steered by the conflation of Islam with national security threat, CVE policing was piloted in Boston, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis - cities with sizable Muslim American communities.

And even before the emergence of CVE, New York Police Department had its own programme of systematic policing and surveillance of Muslim Americans. It was ultimately abandoned because of its brazen violation of civil liberties, external.

CVE is built upon the same old and embedded stereotypes of Muslims injected into the American psyche centuries ago. Such policing links benign and routine religious, political and social activity with "radicalisation".

NYU students protest against the city's police department surveillance programme in 2013

Making the Islamophobia dragnet local chills and erodes the constitutionally protected activities of Muslim Americans, and marks them as threats to their neighbours. Suggesting Muslim Americans need to be under special investigation endorses and emboldens the Islamophobic rhetoric among presidential hopefuls.

This combination stirs anti-Muslim fervour on the ground in America. If the state associates Islam with threat, then surely, that will influence political and media perceptions.

Such rising fear and animus toward Muslims ensures that America may not see a Muslim president anytime in its near future. But it does forecast no end to anti-Muslim rhetoric on the campaign trail.

Khaled A Beydoun is an assistant professor at the Barry School of Law and an affiliated professor of the University of California-Berkeley Islamophobia Project.

- Published26 May 2015

- Published12 February 2015

- Published29 April 2015

- Published8 April 2015