Why don't people see the yeti any more?

- Published

Until recently it was common for people in Bhutan to share stories of their encounters with the Himalayan yeti. But with the arrival of modernity, villagers no longer need to climb high into the mountains, where they once saw traces of the yeti - or thought they did. So a legend is slowly fading away.

Perched on a mountainside surrounded by dense, virgin forest where tigers, snow leopards, and wild boar roam, is the remote village of Chendebji.

It's so isolated that up until seven years ago, before a hydroelectric plant was installed bringing electricity to the village, children here would only go to school for half an hour a day because no-one could afford to buy kerosene to light the classroom.

In the days before electricity, much of the day would be spent searching for firewood to light stoves and walking up into the high pastures to graze their yaks and goats.

While out on the slopes, the people of Chendebji would come across an unusual paw print that struck chill into their hearts.

"I was about nine years old and had gone high up in the mountains to collect dry leaves for the cattle," says Pem Dorji, a woman in her late 70s with a wrinkled face and a wide smile.

"That was soon after a heavy snowfall, which lasted for almost nine nights. The yeti must have come down, trying to escape the snow. I just saw the footprints the yeti left behind."

Sixty years later, Pem still remembers the fear that overcame her. "I couldn't stay there for a moment," she says. She ran nearly all the way home.

Pem Dorji (right) and a friend in the village

Find out more

Candida Beveridge's report was featured on Outlook on the BBC World Service

Children huddle around a pot-bellied stove, listening intently as Pem tells her story. Outside the large two-storey farmhouse, shadows fall across the valley as the evening turns to night. It is a village tradition, at this time of day, to share tales of the "Migoi" as the yeti is called here.

"When I returned home, my parents were quite disappointed to see me empty-handed. I explained that I saw the footprints of the yeti, which were very fresh, as if the yeti had walked past in the morning. I told them I was very scared."

Sitting beside Pem is a young boy, who is hanging on every word. Wide-eyed and excited, he asks if the prints could have been made by another type of wild animal. She shakes her head and goes on to reveal another remarkable detail.

"When I described the footprints to my father, he explained to me that yeti's feet are pointed towards the back, unlike the feet of humans," she says.

It's widely believed in Bhutan that the yeti walks backwards to fool trackers. Pem's version of the story is slightly different - the heel of the yeti's foot is at the front.

Another common belief is that the yeti cannot bend its body, a feature it is thought to share with evil spirits.

According to author Kunzang Choden, this explains why most traditional Bhutanese homes have small doorways. In her book, Bhutanese Tales of the Yeti, she describes how the raised threshold and lowered lintel force anyone who enters to lift their leg and bend their head.

Bhutanese Tales of the Yeti

"The migoi is known by all accounts to be a very large biped; sometimes as big as 'one and a half yaks' or occasionally as 'big as two yaks'. It is covered in hair that ranges from reddish brown to grey black. Its limbs are ape-like and its face generally hairless.

The female has breasts that sag. They are usually encountered alone or as couples but rarely in groups. We are told they communicate with each other by whistling and they exude an exceedingly foul odour.

"On occasions they have been known to grin menacingly and make strange noises; they are said to indulge in mimicry. This aspect of their character has given rise to many tales and legends. It is generally agreed that encountering them is a bad omen, which leads to misfortune and even death in some cases."

Kunzang Choden

More from the BBC: Is the Himalayan yeti a real animal?

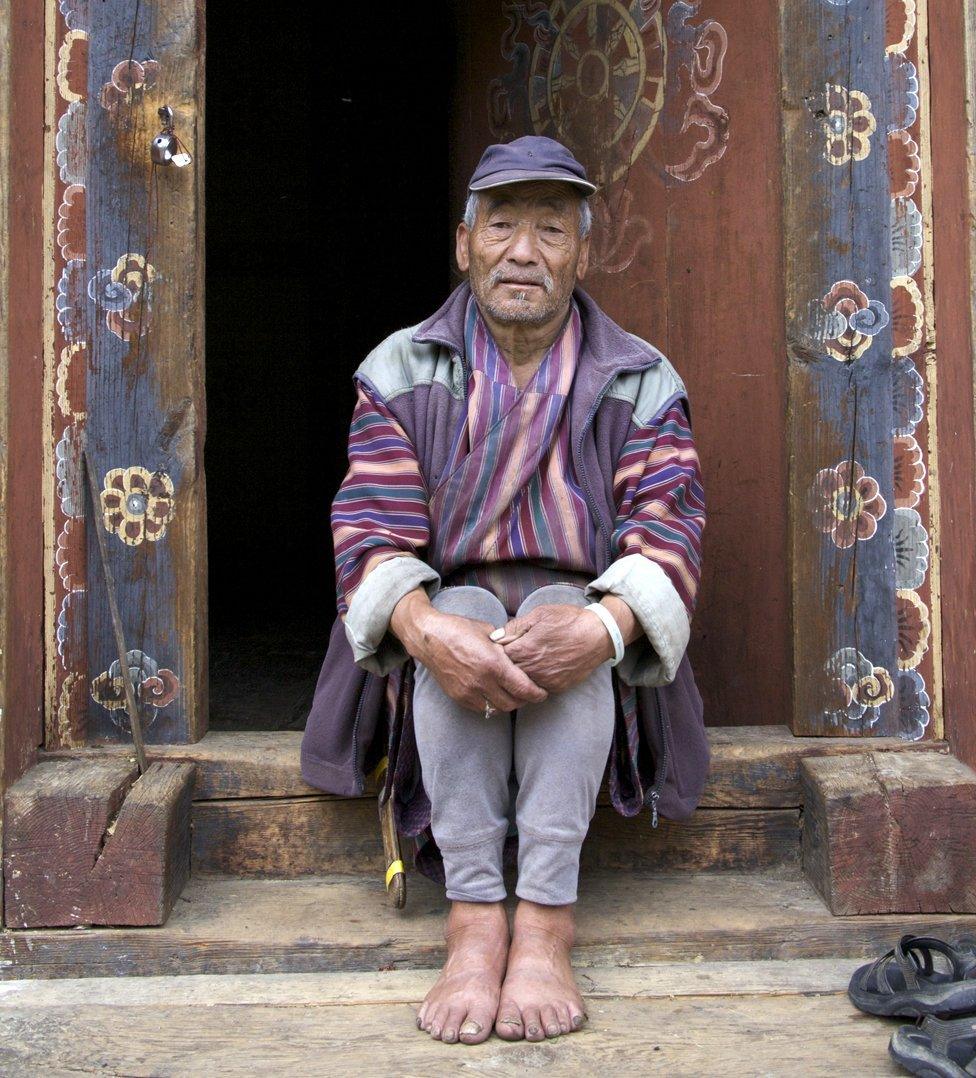

Seventy-three-year-old Kama Tschering often sits in the doorway of his centuries-old farmhouse - the frame is decorated with intricate paintings of mythical beasts to ward off evil spirits.

He agrees to tell me what he knows about the yeti.

"According to the stories that I have heard from my parents and grandparents, the yeti's hair is similar to that of a monkey but its feet and hands are more like ours - but very huge. The yeti is also said to have long, thick hair on its head that falls down to its chest," he says.

Kama Tschering sits in a traditional wooden doorway

"The third King of Bhutan is said to have led an exploration team to search for the yeti. He told his men if they came across it, they should run downwards because the yeti wouldn't be able to see them - its long hair would cover its eyes, obstructing its vision. He told them if they ran up the mountain, the yeti's hair would fall back making it easy for him to catch the men."

Although no-one in this village has ever been attacked by the yeti, Kama has heard of an incident that took place further east.

"A group of men had gone into the mountains to look for a particular tree, which they used to carve masks. When a yeti appeared and chased them, one man disappeared. He hid in a small house used for meditation.

"The yeti is said to have destroyed the house, bringing down the walls. The yeti didn't eat the man but he was brutally killed. All his body parts were dismembered and thrown away."

Then Kama leads me up a steep path, along the edge of the forest. A cuckoo is singing from a distant tree and a delicious scent from some yellow flowers wafts up from the forest floor.

Kama stands on a small rock and points to a mountain pass.

"You see those clouds hovering around the top of the mountains? There's a grazing ground for cattle. We have to walk beyond that point to see the footprints of the yeti."

"When will you go there again?" I ask.

Kama laughs. "I am an old man and I don't think I have the strength to even climb that small hill. There is no way I can walk high up there in the mountains. In fact very few people go there now."

Norbu says he has seen traces of the yeti

The last person in Chendebji to have seen possible evidence of the yeti is a younger famer called Norbu.

The first time was 20 years ago, he says, when he was 18. He was in the mountains with his cattle when he saw a large footprint and the body marks of a yeti in the snow. The mere sight of them made his hair stand on end.

Then, five years later, Norbu says he discovered something very unusual - a lair made out of intricately woven sticks of bamboo.

"The yeti had broken the bamboo trees, folded them into a semi-circular shape, with the two edges of the bamboo in the ground. He had then slept inside the den. I could see the marks left by the yeti inside the nest," he says.

Villager Norbu points out where he spotted a Yeti's lair

News of the lair travelled beyond the village and two months later, two men arrived as Norbu was making wood shingles for his house. They asked to see the lair, so he agreed to stop work and show them. Because it was so far away, the three of them had to spend the night in the yeti's nest. The trip passed off peacefully.

That was the last time anyone in Chendebji saw traces of the yeti.

Now, says Norbu, people don't need to go up to the mountain to collect wood or graze their animals. They cook on gas rings, and farming patterns have changed. The villagers spend more of their time growing cash crops such as potatoes and oil seeds.

Where sundown used to be the end of the day, now, with electricity, villagers weave late into the evening - making rugs and shawls to sell at craft markets as far away as the capital Thimpu.

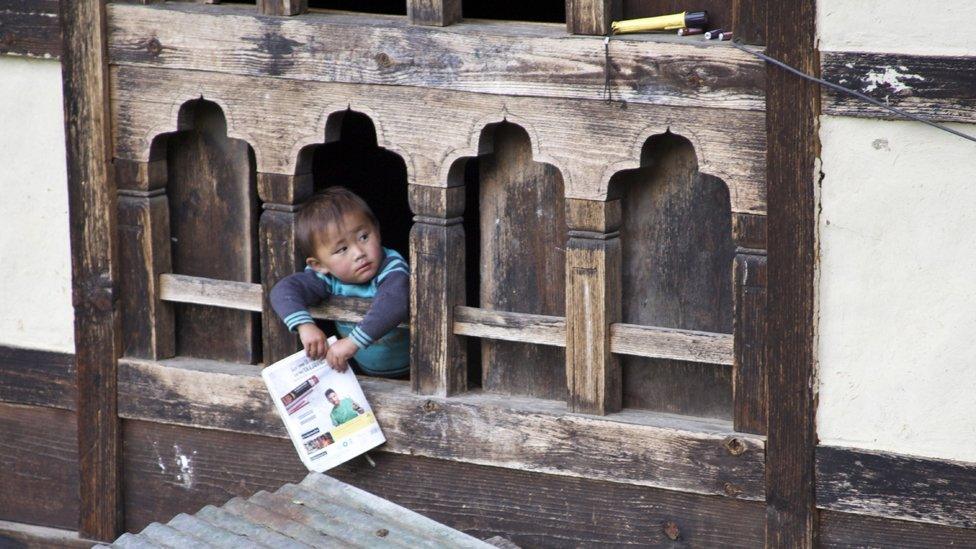

Children from the village of Chendebji

In many ways, lives have improved but the downside, says Norbu wistfully, is that there are no new stories to tell the children.

"We haven't gone to the mountains for more than two decades now and we are really not sure if the yeti is still in our mountain ranges," he says.

"But it doesn't matter, because there is no question the yeti is around somewhere.

"I don't think anyone will ever find it. It's just such a clever animal. It migrates from place to place, and with fewer people going up there, maybe it will never be found. But I know it exists!"

Photographs, unless specified, by Candida Beveridge

Candida Beveridge's report appeared on Outlook on the BBC World Service. Listen to the report on iPlayer or get the Outlook podcast.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published17 December 2014