The place that has wiped out grey squirrels

- Published

The red squirrel has been in severe decline in the UK but one island has completely eliminated grey squirrels to promote a red resurgence. Could it lead to a wider programme of eradication, asks Rachel Argyle.

Once common, red squirrels have declined rapidly in the UK since the 1950s, falling in numbers from about 3.5 million, to a current estimated population of around 130,000.

Anglesey, an island off the north-west coast of Wales, declared itself a grey squirrel-free zone earlier this year after an 18-year cull.

Now, it's been announced that a share of £1.2m of Heritage Lottery Fund money will see the cull of grey squirrels extend to the neighbouring county of Gwynedd, where no native nutkins have been spotted for nearly 70 years.

Rising in numbers - the Anglesey red squirrel

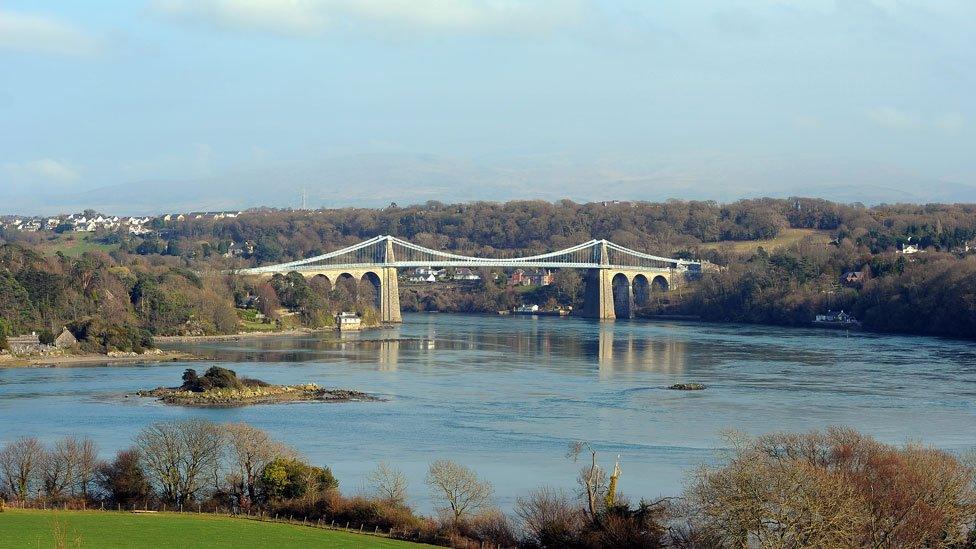

Grey squirrels, said to have been brought to Britain from the US in the 19th Century, crossed the Menai Strait between Anglesey and mainland Wales in the mid-1960s. By 1998 the species had replaced the red squirrel almost completely, with only 40 red squirrels remaining.

It's long been believed that greys act as carriers of squirrel pox - which kills reds.

Their route across the Menai Strait between Anglesey and mainland Wales?

So in Anglesey a plan was hatched to cull the greys. "It began with the vision of Esme Kirby," says Dr Craig Shuttleworth, adviser to the Red Squirrel Survival Trust. "She was a conservation campaigner and undaunted in her fight to see the reds return to Anglesey and the UK as a whole. She never shied away from the issues involved with the cull of the greys and was open and transparent in her efforts."

The island last had a sighting of a grey squirrel in 2013 and has now been declared the first area of the UK to become grey squirrel-free, says Shuttleworth. There are other areas of the UK that are regarded as free of greys but they have always been that way - thanks to natural barriers rather than conscious eradication.

But the culling of one species in favour of another was never going to be an easy task. The challenges ranged from resource and technology issues to garnering landowner, public and political support.

Live-trapping techniques were used to control greys and no poison or any type of spring (kill) trap were used. Captured grey squirrels were allowed to venture out from the wire trap into sacking that had been placed around the entrance. The squirrel would then be moved into the corner of the sack and killed by a single blow to the back of the head. This is regarded to be a humane method.

Over 200 volunteers and a project team, as well as contractors, were involved.

"The reds are rare and the general public wanted to see them," says Shuttleworth. "We needed to ensure that the reds were visible to help the ongoing support for the campaign."

Anglesey's efforts received public backing but not everybody in Britain has welcomed culling projects in the same vein. There are plenty who regard the progression from wanting to preserve reds to a position of backing elimination of greys as irrational.

Businessman Angus Macmillan and his family set up the Professor Acorn website in December 2006 to "redress the balance and seek the public's support for all squirrels, irrespective of their ethnic origin or the colour of their fur".

"I feel it is morally wrong to slaughter members of one sentient species to protect members of another just because they are regarded as aliens," explains Macmillan. "We have support for our aims throughout the UK and abroad." A petition to "Stop the UK grey squirrel cull" has so far attracted almost 140,000 signatures.

The opponents say the trapping and killing of grey squirrels is indiscriminate and cruel. "It causes stress to a wild animal, lactating females are killed leaving their kittens to die a slow and painful death and there is no guarantee that shooting a squirrel, which can easily move faster than the reactions of the shooter, will result in instant death," says Macmillan.

The Professor Acorn campaigners are currently researching whether red squirrels are in fact native to the UK and attack the theory that greys are the cause of the decline of the reds.

"Greys are blamed for the spread of the Squirrel Pox Virus because they have been found with antibodies - but antibodies don't mean they are all carriers all of the time," says Macmillan. "All it means is they have been exposed to the disease and fought it off. A bit like us if we get flu."

The traps do not kill squirrels, so that any reds that are caught can be released without harm

But for the red squirrel conservationists the link is clear and the cull in Anglesey has demonstrated the positive effect on pox transmission and red numbers.

"The cull was never a case of xenophobia," says Shuttleworth. "The greys are an invasive animal and they simply shouldn't be here. The red squirrel project acted as a litmus test for culls of other invasive species. If we couldn't succeed with these cute and furry animals, what hope would the less appealing species have?"

Today Anglesey has the largest and most genetically diverse population of red squirrels in Wales with around 700 recorded on the island.

Other strongholds for the native red include Scotland, the Lake District and Northumberland with some isolated populations further south in both England and Wales including Formby in Merseyside and the Isle of Wight, but will the UK ever be rid of the greys entirely?

"Never say never," says Dr Shuttleworth. "When we first started out, we were greeted with a soundbite reaction that when you kill one grey squirrel, two turn up to its funeral.

"Yet we achieved what we set out to achieve here on Anglesey and there is no reason why, if we take on the many lessons learned, we can't replicate this in other parts of the UK and one day, perhaps the country as a whole."

Nesting boxes for the red squirrels have been put up around Anglesey

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.