Russian plane crash: How has airport security changed?

- Published

A bomb is being cited as the most likely cause of a plane crash which killed 224 people. But has anything changed in recent years to make passengers safer?

Thousands of Britons are stranded in the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh, after the UK government suspended all air links because of security concerns over the airport there.

Intelligence reports suggest the cause of the downing of a Metrojet Airbus 321 bound for Russia was "more likely than not a terrorist bomb", according to Prime Minister David Cameron.

When it comes to smuggling a bomb on board a plane, two main groups of people can do it - passengers or staff, including ground workers and air crews.

There has to be an equal concentration on preventing both, says Norman Shanks, former head of group security at BAA. But, particularly on the staff side, things are patchy, he adds. So, how can anyone ensure airport security operations aren't infiltrated by terrorists?

One way is to screen all workers every time they enter secure areas. This has happened in the UK since the early 1990s, with the European Union deciding to do the same, external in 2004.

"What changed things in the UK wasn't 9/11 - it was the Lockerbie bombing," says Shanks. Some 270 people died in December 1988 when a bomb planted on a Pan Am flight from Heathrow to New York exploded.

"In the immediate aftermath we weren't sure how the device had got on to the aircraft, so we had to work at great speed to deal with the situation and we changed the rules for staff," says Shanks.

All European airport staff have to go through checks every time, however often they leave and re-enter secure areas, in the same way as passengers. There isn't the same system in place in the US and many other countries, experts say.

Passenger security at Sharm el-Sheik is tight, says Zack Gold, a visiting fellow at Israel's Institute for National Security Studies. "If it was a bomb, it was almost certainly due to infiltration of the airport, but not by a passenger. To sneak something through the security screening in the airport would have been [more] lucky than anything else."

Earlier this year, following allegations of an employee gun-smuggling ring at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta Airport, the Transport Security Administration launched an investigation. It considered European-style screening of employees, but found this would not be a "silver bullet" to deal with concerns. Instead, it recommended random checks on employees and improved criminal and security vetting before staff were taken on.

Staff at UK airports have to undergo criminal records checks, but the Civil Aviation Authority does not reveal who has undergone further security checks, external "for reasons of national security".

"I don't have much confidence in the vetting of people," says Shanks. "If you have got convictions, they will come up." But there are people who can carry out terror attacks without previous convictions, known as "clean skins", he adds.

Air India flight 182 from Toronto to Delhi was blown up in 1985, with the loss of 329 lives. Prior to this time "the significant threat to civil aviation was seen as the hijacking", says the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), part of the United Nations. Within a few years there was, worldwide, a "reasonably effective screening system for passengers and their carry-on luggage", it adds.

Since 2006 the amount of liquid allowed on a plane has been monitored

After the attacks in the US on 11 September 2001, the ICAO tightened up its recommendations on checking passengers and luggage as well as access to planes and secure areas. But because - unlike the EU in Europe - it has no jurisdiction, it can only encourage change.

One thing that has undoubtedly improved over the last few years is the technology available to airport security. Electronic scanners are now able to detect explosive materials. Once staff are alerted, they use scanners to look for other likely components of potential bombs carried by the person with the materials or their companions.

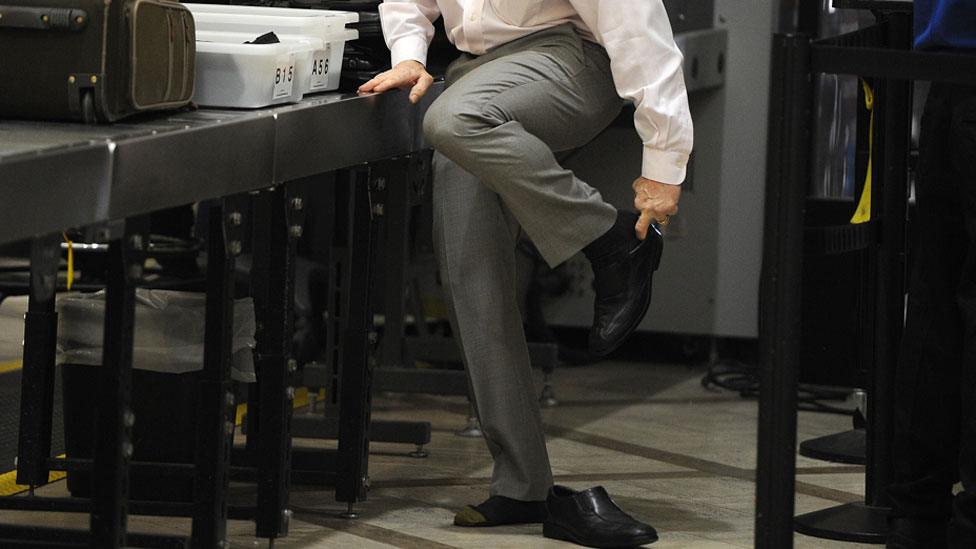

Other measures have come in in response to particular incidents. In December 2001 Briton Richard Reid tried to blow up an American Airlines flight from Paris to Miami using explosives in his shoe. This led to checks on people's footwear.

In 2006 a planned attack on seven transatlantic planes using liquid explosives was foiled. In the aftermath, strict EU and US limits were placed on the amounts of liquids passengers could take on board.

"At first, straight after the plot was foiled, no one knew what it actually involved," says David Learmount, an aviation journalist specialising in safety and security issues. "They said 'We know that these guys are up to something, but we've no idea what it is.' So passengers were banned from taking anything on board as hand luggage, even paperback books."

It wasn't until the real nature of the plot was discovered that the specific liquids ban came in, Learmount adds.

In recent years, full body scanners have been used at UK airports, including Manchester, external. But in 2010 Home Secretary Alan Johnson told MPs that "no one measure will be enough to defeat inventive and determined terrorists, and there is no single technology that we can guarantee will be 100% effective".

Some UK airports, such as Manchester, have started using full body scanners

Learmount agrees, arguing that it is vital that all countries abide by United Nations standards, investing in personnel and training, while fighting to ensure corruption doesn't undermine standards. Terrorists are "looking all the time to detect any method of getting round security", says Learmount, adding: "Things are better than they were a few years ago. There wasn't universal screening of hold luggage around the world before 9/11." There is now, more or less, he adds.

Should it be proved that the Metrojet Airbus 321 crash was caused by a bomb, it will be one of few such attacks that have succeeded in their aims. The last major loss of life in such an incident happened in southern Russia in 2004, when two planes crashed, killing 89 passengers and crew.

In that sense, the changes brought in after 9/11 and the Lockerbie and Air India disasters seem to have helped - at least until now.

But the ICAO reminds us that "acts of unlawful interference continue to pose a serious threat to the safety and regularity of civil aviation".

Airport security measures

Check in: Strict regulations exist about what can be carried. No sharp objects or liquids in containers larger than 100ml. Maximum size for hand luggage is typically 56cm x 45cm x 25cm.

Hand luggage: Scanned for illegal items with an X-ray machine. Sniffer dogs and chemical hand swabs may be used to detect explosives. Passengers may be asked to prove electronic and electrical devices in their hand luggage are sufficiently charged to be switched on.

Body scanner: Passengers pass through a metal detector and or body scanners which produce an outline image showing items concealed beneath clothing or on the body.

Passport control: Biometric passports used by some countries use facial recognition technology to compare passengers' faces to the digital image recorded in their passport. Details are then automatically checked against Border Force systems and watchlists. Iris recognition is also used at some airports.

Boarding pass check: Final check before getting onto the aircraft is usually the boarding pass control. Most airports have automatic readers that verify the pass to confirm the passenger is boarding the flight that is carrying their checked-in luggage.

Baggage check: Checked baggage passes through large-scale X-ray machines and may be checked by sniffer dogs. All bags are kept completely separate from passenger areas in the terminal.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.