What is it like to have a prison in your town?

- Published

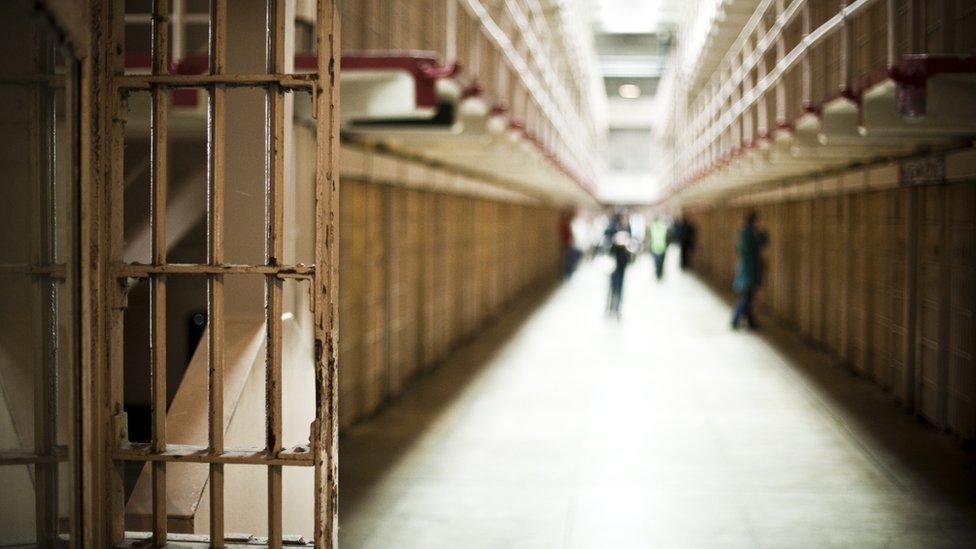

Plans to close the UK's Victorian jails and sell them for housing are under way. But what is it like to live near a prison and what happens when one closes its doors for the last time?

The last inmates of HMP Reading left two years ago this November. It was a jail that once held 320 prisoners. Built in 1844, the prison was made famous by Oscar Wilde. "This too I know - and wise it were if each could know the same - that every prison that men build is built with bricks of shame," he wrote in his poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

The prison was finally closed in 2013 and is now on the market. The government has announced plans to close other "relics from Victorian times" and move around 10,000 prisoners to new facilities. They say that this will make way for more than 3,000 new houses in areas of prime real estate.

But closing a jail often means losing a building that has dominated a local community for years. "It is painful in some places when a prison closes," says Peter Dawson, deputy director of the Prison Reform Trust. Jails tend to become major sources of employment for the area around them. The new "super-prison" being built in Wrexham is expected to bring £23m a year to the local economy and 1,000 jobs.

'Prisoner 633'

Reading prison's most famous inmate was the writer Oscar Wilde, who served eighteen months of a jail sentence there between November 1895 and May 1897

During his incarceration, Wilde was addressed only as Prisoner 633

He had been sentenced to two years' hard labour for "gross indecency" - a term used to describe homosexual acts

After his release, Wilde wrote his famous poem The Ballad of Reading Gaol, describing a hanging at the prison; it contains the famous line "each man kills the thing he loves"

A prison tends to close amid dire warnings about the impact that it will have on local businesses. When Bullwood Hall Prison in Essex was shut in 2013 it was reported that it would have "huge knock-on effects", external for the local area.

Prisons can also impact on tourism. A Napoleonic jail might seem like an unlikely attraction but Dartmoor Prison in Devon, and its nearby museum, has made a name for itself as a place to visit. The museum says, external that more than 35,000 people a year travel to Dartmoor to hear the stories of its notorious inmates and their escape attempts across the moor. "An eye opener," wrote one visitor on the website. "Puts you off doing wrong things."

Dartmoor prison set against the moors

On Monday, the Ministry of Justice has confirmed that the lease on Dartmoor prison will not be renewed. "You would never want to say that we can continue running prisons as an employment opportunity," says Dawson. He adds that not all old prisons are in areas that make sense.

Victorian prisons were built where they were needed 100 years ago, he explains. Others now occupy old military bases from World War Two. Some prisons such as Haverigg in Cumbria, external are in areas so remote that the nearest neighbour is more likely to be a flock of sheep than a thriving small business community. "If you look at a map of Cumbria, where we put the nuclear power station and then head about 10 miles south to somewhere even more remote, you find Haverigg prison," says Dawson. "It doesn't belong to a local community at all.

"If we want prisons to be about changing lives then we want the communities to own that and say that they have a responsibility with what happens to people," he adds. There are communities that are able to engage with the prisons in their midst. Cafe Britannia, external in Norwich is open seven days a week and is staffed with volunteers from the nearby jail.

HMP Peterborough was built in 2005, despite strong local opposition

Co-founder Davina Tanner says that the public have "celebrated" the project. "They have picked it up as their own and want to do their bit for the community and to help reduce reoffending," she says, adding that demand is so great that on any given day they might prepare 225 meals for breakfast.

There are similar rehabilitation projects across the UK. Blantyre House was a prison which focused on re-integration. The staff were locally employed and prisoners would go out to work in the community, explains Mark Icke from the Prison Governors' Association. But it was closed temporarily in January. The Ministry of Justice said yesterday that its future had not yet been decided.

"People were upset that the prison was closing," adds Icke. "They liked having it on their doorstep and liked knowing that these men were going out and doing something meaningful." Concerns were raised over where inmates would be relocated to and whether they could be kept close to their families and support networks.

But the idea of living near a prison and engaging with its inmates does not appeal to everyone. HMP Peterborough was opened in 2005, external despite strong local opposition. Proposals to build a new facility frequently cause protests. Wrexham in Wales has divided the opinion of its neighbours. Some residents are worried about the effect that the largest prison in the UK could have on house prices. Others have said that they are concerned about security.

HMP Dorchester is due to be redeveloped

There will always be residents who breathe a sigh of relief when a prison is closed down. But Icke says that people often get used to their presence. "Prisons tend to have been around for a long time," he explains. "Generally people move to be near one rather than having one put near you."

What happens to a prison after its closure can depend on its architectural value. When Dorchester jail shut its doors in 2013, many people worried about its redevelopment. "The prison was very much a part of Dorchester, both in terms of employment and housing prisoners close to their locality," says Alan Rowley from the Dorchester Civic Society.

Developers are now working with archaeologists and conservationists to keep important features such as the 18th Century gatehouse. A planning application is due to be submitted soon and is expected to incorporate a museum. "When the prison closed I think there was sadness," says Rowley. "But it was also an opportunity."

Oxford's former prison is now a successful hotel

Several other prisons have been converted successfully. HMP Oxford became a hotel in 2005 and kept some of its old features, from cell doors to metal staircases. Some prisons do deserve to be bulldozed so that something more sensible can be done with the space, explains Dawson.

Prison reform could be a chance to look beyond building design and work out where jails are needed and the types of communities they serve, he says. Links with the local area are not always as strong as they need to be. People should expect to know what is going on just over the wall.

The Magazine on prison

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.