Five things prisoners' books show about life in prison

- Published

Vicky Pryce, the economist convicted of taking speeding points for disgraced cabinet minister Chris Huhne, is writing a book inspired by her time behind bars. What can people glean about life inside from books written by prisoners?

Pryce's book Prisonomics will explain the economics of imprisonment. She joins a long list of people who have squeezed a book out of their experience of life inside.

All have shown something about the nature of incarceration.

You meet some interesting characters

Miguel de Cervantes was trying to make a crust as a tax collector in his native Spain when he found himself unable to account for all of his takings.

During his subsequent stint in a debtors' prison, he claims to have conceived the book that would become the most influential novel in the Spanish language.

Don Quixote is "brimming over with anecdotes and digressions", says Dr Alexander Samson, lecturer in Spanish "golden age" literature at UCL, "the kind of thing that one might experience a great deal of" while twiddling thumbs and chewing the fat with fellow inmates.

It features "criminals and low-lifes", Samson notes. They are characters that might be based on real-life prisoners who shared their stories with the author, perhaps embellishing their tales with the sort of flight of fancy that we might now describe as quixotic.

It helps to be self-reliant

He had enjoyed high office and great riches. He would soon succumb to a grisly death, executed for treason.

![A manuscript depicting Boethius. [Image by permission of University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections]](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/304/mcs/media/images/67646000/jpg/_67646685_h374_0004r.jpg)

But Roman philosopher Boethius was determined to look on the bright side.

Imprisoned in about the year 523, apparently in solitary confinement, the blue-blooded philosopher sought solace in writing. He imagined himself in a prolonged debate with the concept of philosophy, embodied in female form.

Fortune has always been capricious, Philosophy tells him: "What! Art thou verily striving to stay the swing of the revolving wheel? Oh stupidest of mortals, if it takes to standing still it ceases to be the wheel of fortune."

In the narrative of the Consolation of Philosophy, the resulting blend of poetry and prose, Boethius transforms from a snivelling wretch to a more enlightened soul, having been convinced that his comprehensive downfall is part of God's plan.

"He is able, on his own, to muster the intellectual defences that he needs," explains Boethius expert Prof Joel Relihan of Wheaton College, Massachusetts.

You have plenty of time to dwell on the past

"I blame myself terribly. As I sit here in this dark cell in convict clothes, a disgraced and ruined man, I blame myself. In the perturbed and fitful nights of anguish, in the long monotonous days of pain, it is myself I blame."

Oscar Wilde's 50,000-word letter to his ex-lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, was written in 1897, towards the end of a two-year sentence for gross indecency, and published posthumously as De Profundis - Latin for "from the depths".

"For prisoners there is no present and the future is hard to contemplate," says Thomas Wright, author of two books about Wilde. Dwelling on the past is therefore "very typical of prison literature".

Wilde analysed his downfall in detail. "I amused myself with being a flaneur [a stroller], a dandy, a man of fashion.

"I surrounded myself with the smaller natures and the meaner minds. I became the spendthrift of my own genius, and to waste an eternal youth gave me a curious joy."

The "opulence" of the letter's language, which is full of "internal rhymes, lush purple poetic prose, and very long sentences", represents the "direct opposite of the hideous conditions in prison", Wright contends.

It might not weaken your political convictions

Birmingham, Alabama, was once the "most thoroughly segregated city in the United States", Martin Luther King argued.

After being arrested there in April 1963 and locked up for 11 days for leading a civil rights march, King composed the lengthy "letter from Birmingham jail, external" to rebut criticism from eight white clergymen who had accused him of being a meddling outsider.

"I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham," he wrote. "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny."

Negotiating for civil rights had taken too long, he said: "For years now I have heard the word 'Wait!' It rings in the ear of every Negro with piercing familiarity. This 'Wait' has almost always meant 'Never'.

"But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim... then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait."

King made his I Have a Dream speech in Washington later that year, and was awarded the 1964 Nobel peace prize for his commitment to nonviolent protests against racial inequality.

You can get used to it

Much recent prison literature might seem more humdrum - diaries abound. But for Prof David Wilson of Birmingham City University they are invaluable subjects of scrutiny, shedding light on a hidden world.

"Prisoners rarely have a voice," the former prison governor says. "People who write books as prisoners are providing a large number of people with a voice who don't usually have one."

He distinguishes books written by "straights", like Pryce, from those written by career criminals, or "cons". "The classic con account is by Noel 'Razor' Smith," Wilson says.

Smith reveals a deep understanding of "how the staff will operate, how the prison culture will operate, how to survive... and prosper" in his book A Few Kind Words and a Loaded Gun, Wilson explains.

Straights, meanwhile, find themselves in a "complete and utter alien world... worried about being raped, about being stabbed", he explains.

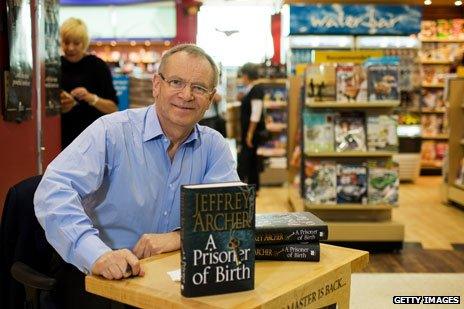

But they soon find a niche. He cites Jeffrey Archer, who was imprisoned for perjury and published a detailed account of the experience. "He performed a role in helping prisoners to read letters, suggesting who they could write to," Wilson says.

A book by convicted murderer Erwin James, who forged a successful writing career by chronicling his incarceration, showed that his "mechanism for coping with life inside has succeeded so well that he has left jail behind", according to one reviewer, external.

But James believes that Pryce's book, informed by her background in economics, could be a much-needed catalyst for change.

He argues, external: "Focusing on the exorbitant amount the taxpayer pays for our failing system... may be just what politicians need to initiate real reform in our prisons."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external