Why are so many British homes empty?

- Published

The Bezier building

Hundreds of thousands of homes across the UK are unoccupied, despite widespread concern about a housing shortage. Why would someone own a property and leave it vacant?

The Bezier building stands right in the middle of London's Old Street area, one of the most expensive and fashionable parts of the UK. Flats inside the apartment block can cost more than £1m and monthly rents of £2,000 are easily achievable.

But more than five years after its completion the Bezier, shaped like two sails full of wind - seemingly a metaphor for the area's forward-thinking economic confidence - is almost half-empty.

Islington Council complains that, as of this July, 42% of the building's units still had no registered voters living in them. The authority blames a phenomenon known as "buy-to-leave, external", where rich investors, often from abroad, purchase property and leave it empty, not bothering to collect rent money while adding to the nation's housing shortage.

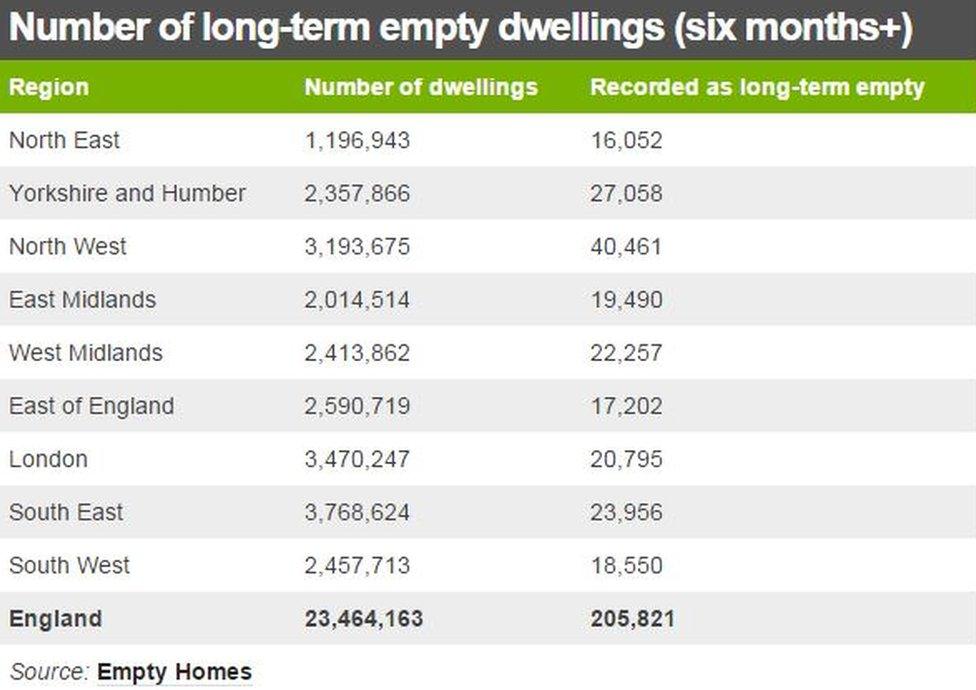

Despite widespread anxiety about a shortage of housing supply, there are 610,123 empty homes in England, external, according to the government. Of these, 205,821 have been unoccupied for six months or more, the official definition of "long-term" emptiness.

In September last year, Scotland had 31,884, external long-term empty properties. In Wales, 23,171 were empty for six months of more during 2014-15, the Welsh Government says.

So why would anyone leave empty a property asset that could be rented out or cashed in?

London Mayor Boris Johnson has criticised some owners for using new-build homes as "blocks of bullion in the sky", while adding that putting restrictions on investment in the city would be wrong.

To most people, throwing away vast amounts of rent money while waiting for prices to go up might sound like economic madness. Not according to property expert Henry Pryor, who says investors leaving flats empty are in fact being highly calculating. The costs of letting, including wear and tear and administration, can outweigh any money taken from rent, he says.

And, at the top end of the new-build market, many buyers pay a premium for pristine apartments. "Some buyers don't want to live somewhere second-hand, just as they would feel if buying a Rolls-Royce or an Aston Martin," says Pryor. "This applies even when they're buying a place that's five years old."

However, buy-to-leave, centred around London, accounts for a small percentage of vacant properties, according to the charity Empty Homes. More often it's because of ordinary financial concerns, it adds.

"One of the most common reasons that properties are empty is because the owner cannot raise the money to do the property up to let it out, or sell," says Helen Williams, chief executive of Empty Homes. "Perhaps they previously rented it out and it now needs more works done to it, or maybe they inherited it." If property is jointly inherited, it can take years for beneficiaries to decide what to do with it, she says.

The Dale Court house, before and after renovation

A modern house in, external Barry, in Vale of Glamorgan, attracted fly-tippers after it was left empty. It was renovated and offered once again for rent in a project overseen by the registered social landlord United Welsh.

A house in York Road, in the North Yorkshire resort of Redcar, was left abandoned for years, gradually rotting away, the owner unable to fund improvements. "It was a mess," says Ian Cockerill of Community Campus 87, external, the organisation that oversaw the renovation of the house, using the project to train apprentices. "It was right at the entrance to the town and was putting people off."

A study of government statistics, external for England by Empty Homes found that, overall, areas in the North tended to have a larger proportion of unused residential properties than those in the South. Seaside towns were also more likely to experience the problem.

The house in Marine Parade, Folkestone had been left in a state of neglect

One such was Folkestone, Kent, external, where a house on Marine Parade, used to train spies during World War One, was abandoned. The building is now being converted into 12 flats after years of neglect.

In some areas it's not just individual homes but whole streets that are empty, as a result of areas becoming less desirable. The causes can be purely economic, such as industries closing down, but research, external carried out in Denmark in 2008 suggests a neighbourhood's decline in reputation - such as when crime and vandalism are seen to rise - can also cause an exodus.

But, the study added, higher rates of owner-occupation tended to reduce the effect. With this type of thinking in mind, Liverpool City Council, external has sold off some derelict houses for just £1 each, on the understanding that they will be done up to a decent standard, regenerating the affected areas.

The street where houses cost £1

Houses on an all but abandoned street in Liverpool are being sold for £1. But 30 years ago it was a vibrant inner-city street, so what went wrong, asks Stephanie Power.

Councils in England can charge owners 50% extra in council tax if owners leave properties empty for two or more years - a deterrent for many, but by no means to the wealthiest investors.

Another power is a compulsory purchase order, external, applicable only if officials can show they've tried to encourage the owner to bring a building back to "acceptable" use.

In 2009 Kensington and Chelsea recommended imposing one, external on a mews cottage in Alba Place, a street off Portobello Road in Notting Hill, west London, where today several properties are estimated to be worth more than £1m. This was six years after a rodent infestation brought the empty building to officials' attention.

The council identified damp and mould problems, drainage issues and structural risks. It hadn't become an "eyesore", but this mainly was because neighbours, showing concern over the state of their area, had "redecorated the front elevation at their own expense".

Brighton and Hove Council demanded a compulsory purchase order in 2013 after a house in Chester Terrace had remained empty for 35 years, external. A neighbour had complained about scaffolding being left up, external at the back of the building for 14 years.

Brighton Council issued a compulsory purchase order on the house in Chester Terrace

But compulsory purchase is seen as an intervention of last resort. So, in 2006, the Labour government brought in Empty Dwelling Management Orders (EMDOs), allowing local authorities in England to take over the management of some residential properties that had been empty for at least six months and where there was "no reasonable expectation" of them being occupied in the near future.

By 2011 only 64 applications had been made and 43 had been granted across England. However, the coalition government changed the law so that a property had to be empty for at least two years before an order could be issued, arguing that it was undermining property owners' rights. They also had to be proven magnets for vandalism, squatters and other forms of anti-social behaviour to qualify. These restrictions came into force in 2012.

In 2013 Newcastle City Council issued an EDMO for a mid-terrace ground-floor flat in Denwick Terrace, a residential street in Lemington, saying it would "improve the amenity of the local area" for the property to be "lived in, rather than empty and boarded-up".

Housing shortages mean councils are becoming keener to work with owners of lapsed homes to create much-needed stock.

The National Housing Federation estimates 974,000 homes needed to be built between 2011 and 2014, but that figures from 326 councils showed only 457,490 were completed. The homelessness charity Shelter says the main emphasis must be on construction, external.

But the UK's empty housing stock, whether old and dilapidated or new and purposefully unoccupied, needs to be utilised more thoroughly, says Williams.

This can be "transformed into new homes for people in search of decent housing at a price they can afford", she adds. "Creating new homes from empty properties should go alongside building new homes to address housing needs."

The Department for Communities and Local Government says the number of empty homes is now "at its lowest since records began" and that more than 100,000 long-term empty properties have been brought back into use since 2010. The government offers councils the same financial rewards for bringing empty homes back into use as it does for building new ones, it adds.

Ministers are committed to "helping anyone who works hard and aspires to own their own home to turn their dream into a reality", a spokesman says.

Over the summer Islington Council granted itself powers to prosecute owners of new-build homes who leave them empty for longer than three months. This could result in fines, prison sentences and even seizure of the property. This won't affect existing buildings like the Bezier.

A spokesman for Bezier's developer Tudorvale says the units were sold in good faith to people who "worked hard" to buy the property, adding that he could not understand why an investor would want to leave a flat empty, such would be the loss of rental income.

"The number of potential homes affected by buy-to-leave isn't huge in a city the size of London, with a housing stock of several million," says Pryor. "But as a percentage of new-built properties, the ones intended to help deal with the housing crisis, they account for quite a significant percentage. It's about whether property is regarded as a home or an asset."

Photographs of the Bezier building by Phil Coomes.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.