Becoming radicalised – and keeping a secret

- Published

Tashfeen Malik and Syed Rizwan Farook

It doesn't take much to show support for the so-called Islamic State - you can do it on Facebook. Becoming a violent extremist is more complicated, however.

Before the mass shooting in San Bernardino, California, Tashfeen Malik reportedly wrote a Facebook message in support of an Islamic State leader. FBI officials are looking into reports that she'd pledged allegiance to the militants.

The investigation is under way, and it's unclear to what extent Malik, who was 27, and her husband, Syed Rizwan Farook, 28, were radical extremists - and also how they hid their plans, and weapons, from friends and family.

The story of people who've become radicalised under the radar is a disturbingly familiar one, however.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev

The frequency of lone-wolf attacks - assaults carried out by individuals - has increased in the US and other Western countries over the past several decades.

The number of these attacks has gone from 30 in the 1970s to 73 in the 2000s, according to a new report, external.

Some of these individuals identified with an organisation such as IS or al-Qaeda while others followed their own extremist beliefs and underwent a more personal form of radicalisation.

The accounts are chilling, and they include people such as Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev, who carried out the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, killing three and injuring over 260 people, and Mohammad Youssef Abdulazeez, who killed four marines in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Their stories are not only brutal. They're also idiosyncratic and defy easy categorisation.

Still in many cases individuals are drawn to IS or other extremist groups because they're unhappy in their own lives and are looking for a cause that's bigger than themselves.

"The radicalisation process has been triggered by a personal crisis - the loss of a loved one, the loss of a job," says Indiana State University's Mark Hamm, the author of The Spectacular Few, a book about extremism.

"Typically there's somebody in cyberspace who shows them a way - walks them from the brink of a cliff."

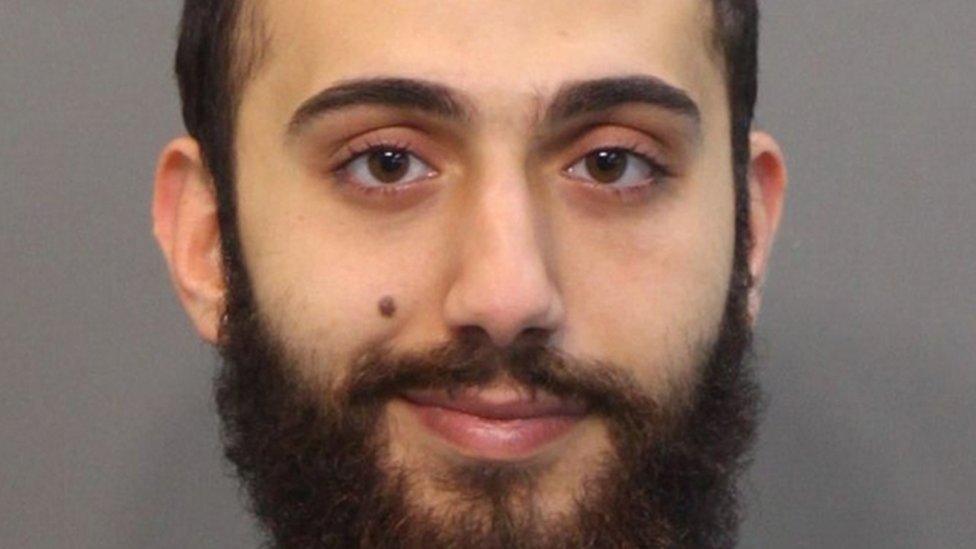

Mohammad Youssef Abdulazeez in a booking photo after being charged for driving while intoxicated

They may be drawn to radical beliefs in a way that escapes detection. In some cases, they're simply good at hiding things.

"It requires a certain effort but many people can compartmentalise their lives," says Mitchell Silber, former director of the analytic unit of New York Police Department's Intelligence Division and the author of The Al Qaeda Factor.

In other cases, their friends and family members may see signs of trouble and decide to ignore it. As New America Foundation's David Sterman, who does research, external on Westerners drawn to Jihadist groups, says, the cost of noticing can be high.

If a friend or family member reports someone for making radical comments or showing signs they're an IS supporter, they could be placed under surveillance. They can be sent to prison, he says, "even for thinking of going to Syria".

Most of those individuals who are drawn to extremist groups eventually lose interest and drift away from the teachings. For these individuals, it was enough simply to shout extremist slogans - and vent.

The important question, says Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham University's law school, is: "How do you distinguish between kids who are just acting out online, and those who are committed rebels?"

That's the problem intelligence officers are struggling with as they try to sort out where danger lurks - so they can stop another mass shooting from being carried out.

- Published17 November 2015

- Published2 September 2014