The search for a 450-year-old heart

- Published

The search for a missing 450-year-old heart and its golden box has led researchers to a small town in south-west Hungary. The organ once belonged to an Ottoman sultan.

Where do you pitch your tent when you arrive with your army to besiege a city? When you've tramped for weeks through an unusually wet summer, when some of your camels even drowned in the Danube? Where else but the high, dry ground, a good vantage point from which to see the enemy castle, and where your troops can see you, to gather courage from your mere presence.

But where do your men bury your heart, if you are careless enough to die of old age, in your tent, as poor Suleiman did on 6 September 1566, on the eve of victory? While his body was taken back to the imperial capital, to Constantinople, to be buried in what became the Suleimaniye Mosque, his heart remained forever in Hungary, as they say.

Suleiman was one of only two sultans to die on the battlefield. The tomb of the first, Murad, still stands lonely and proud on the Field of the Blackbirds in Kosovo, where he fell in 1389. But when Austrian Habsburg troops retook Szigetvar in 1692, they razed every Ottoman building to the ground. And historians have puzzled ever since about Suleiman's resting place. The more so since there were rumours that his heart had been buried in a golden case.

A team of Hungarian and Turkish geographers, historians and archaeologists, generously supported by Ankara, believe they have the answer. On a vineclad hilltop to the east of Szigetvar, beneath a carpet of broken Ottoman tiles, they claim to have unearthed not just the tomb of Suleiman, but a mosque, a dervish lodge, a military barracks and a city wall.

Drone footage of the excavation, courtesy of Norbert Pap

The heart, alas, is no more. The researchers found a deep hole, dug by treasure hunters when the building was destroyed. The rubble they left behind, according to the experts, proves this was indeed a royal tomb.

For three years, the archives of Istanbul, Budapest, Vienna, and a host of small towns, churches and libraries, have been ransacked for clues. The latest aerial and soil research techniques have been employed to calculate the erosion of hilltops by wind and rain, and the draining of marshland over 450 years. Even the shards of Ming dynasty vases, such as Ottoman rulers might have kept in their places of worship, have been identified in the soil beneath ageing Hungarian apricot and apple trees.

A fragment found at the site in Szigetvar, Hungary

The best clue, Prof Norbert Pap, who led the team, tells me, was a 17th Century copper-plate engraving of the Hungarian nobleman, Count Pal Esterhazy. Behind the rear hooves of his horse is a view of the town of Szigetvar, and just to the east, on a hilltop, another town, or cluster of imposing buildings, marked Turbek.

However the claim of Turbek's church, St Mary's, to be the final resting place of Suleiman's heart has been discredited. Even the Hungarian-Turkish friendship park, on the shore of the Almasi stream, has been ruled out. All lines of enquiry led to the vineyards which have long served the people of Szigetvar.

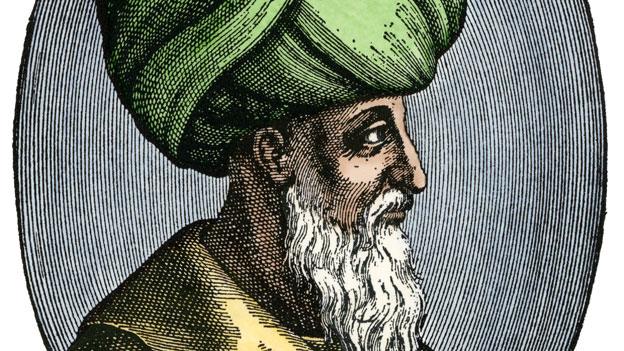

Who was Suleiman?

Sultan Suleiman I, born c. 1494, died 1566

Known as the Magnificent, or the Lawgiver on account of his creation of a legal code which lasted hundreds of years

He ruled the Ottoman Empire at the height of its military, financial and cultural power

When he died, the empire stretched into parts of North Africa, the Balkans and present-day Hungary

But why does all this matter? Why invest hundreds of thousands of euros, Hungarian forints or Ottoman lira in yesterday's man, however magnificent?

For the Turkish government, because they are empire-building again. Seeking an influence they lost in the Middle East when Ataturk dismantled the Islamic Caliphate in the early 1920s. And in eastern Europe, they are quietly restoring iconic Ottoman sites. A reminder to modern European Union states to treat Turkish heritage, Turkish investors, and Turkish tourists, with the respect they deserve.

The Hungarian government, at least, is open to that message. The Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orban, has compared himself to the captains of Hungarian castles, defending Christian Europe against invading Muslim hordes, in the guise of modern-day migrants. But he also tells another tale, what he calls Hungary's "opening to the East", and recently delighted Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan by reminding him that both Turks and Hungarians are, as he put it, grandchildren of Attila the Hun.

But what would Suleiman make of all this fuss about the search for his old campsite? I ask Prof Pap. I'm sure he would have a good laugh, he says.

More from the Magazine

In 2013, a group of Hungarian researchers published a report on the whereabouts of Suleiman's heart. Read Nick Thorpe's report on the roots of the country's fascination for the Ottoman sultan.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30. Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule or listen online.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.