When is it right to remove a statue?

- Published

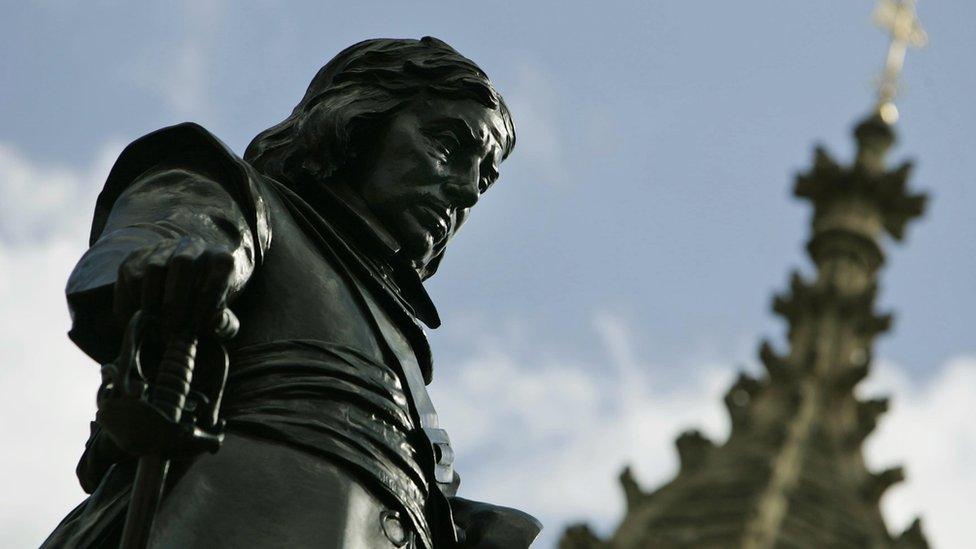

Rhodes's statue stands on the building named after him at Oriel College, Oxford

Activists are campaigning for a statue of Cecil Rhodes to be removed from an Oxford college. The movement against him is part of a wider drive to get rid of monuments to figures who are now intensely controversial.

The problem with statues is that stone or bronze is meant to last forever, but reputations crumble much more easily.

Cecil Rhodes is a classic example.

Earlier, this year the #RhodesMustFall movement succeeded in getting the statue of the diamond tycoon and imperialist removed from the University of Cape Town.

Students at the University of Cape Town celebrate the removal of Cecil Rhodes's statue in April

Rhodes believed the English were a "master race" and he was instrumental in the seizure of swathes of African land. But the movement against his statue was aimed at wider targets - continuing domination of education by white academics and generally addressing the lack of change in modern South Africa.

"He represents the former colonial representation of this country - supremacy, racism, misogyny," said student representative Ramabina Mahapa. "The statue represents what is wrong with society." Leader of the opposition Economic Freedom Fighters Julius Malema said: "It is through collapsing of these types of symbols that the white minority will begin to appreciate that there's nothing superior about them."

The movement spread to other universities in South Africa and has now arrived in Oxford, where Oriel College is under pressure to take down a statue marking Rhodes's large financial contribution. But a petition has been countered by a series of figures counselling caution, including historian Mary Beard who said it was "not the job of the present to tick the past off".

One letter writer to the Daily Telegraph argued: "The trouble… is that almost every person of that era held opinions that were commonplace at the time but are at odds with modern thinking. Taken to its extreme, this approach would lead to the eradication of almost every building and statue commemorating notable figures of the past, including the Albert Memorial and Nelson's Column."

And indeed rows over statues are increasingly common.

The US is undergoing a cultural battle over symbols of the Confederate era that has seen a statue of Jefferson Davis removed, external from the University of Texas-Austin. Students at the University of Missouri also asked for a statue of Thomas Jefferson - third president of the US - to be taken down as he was a "racist rapist".

Statues of Lenin have been toppled in many countries that have rejected communism, but last year in in some cities in eastern Ukraine, pro-Russian protesters rushed to protect statues at risk of being torn down. Equally symbolically, a statue of Lenin in Odessa was turned into Darth Vader.

Jefferson Davis's statue was removed from the University of Texas-Austin in August 2015

In the UK, a row is rumbling on in Bristol over the commemoration of Edward Colston, external. The 17th Century businessman and MP was a key figure in the Royal African Company and the transport of many thousands of slaves.

But he was also a key philanthropist in the city - which was a major hub for the wider trade around slavery - and is remembered with a statue and an annual day of celebration. Now there is intense controversy over whether the statue should be removed, external.

There are a slew of figures in London from the same period - all involved in some way in slavery - whose statues are still standing, external.

The legacy of slavery, imperialism and race aren't the only reasons for campaigning against a statue.

The 1992 unveiling of a statue of Arthur "Bomber" Harris, head of the RAF's Bomber Command in World War Two, created a wave of protest, culminating in sustained vandalism. Harris was criticised for having masterminded saturation bombing of areas of Germany that cost large numbers of civilian lives.

One letter writer to the Times said: "We need not be proud of a man who, for all his professional skill and dedication, committed the force to acts of destruction devoid of direct military value, of which people of humane and Christian sentiments have long been bitterly ashamed. "

Another wrote: "I read with disbelief and disgust that a monument is to be erected to 'Bomber' Harris. Certainly, a public remembrance to the very brave British airmen is long overdue, so long as the names of the instigators of the barbarity are not mentioned. I survived the air raids on Cologne as a teenager."

The controversial statue of Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris in central London

Other statue subjects have been controversial from the start. Oliver Cromwell is credited by many with being a key figure in the development of Western democracy. But he also stands accused of leading massacres in Ireland.

When a statue of him was proposed for Westminster in 1895, it was met with bitter opposition in Parliament from both Irish Nationalists and Conservatives. A century later a group of MPs campaigned to have it melted down.

The stimulation of debate prompted by a call to remove a statue can be a good thing, says historian Prof Madge Dresser, from the University of the West of England, who has written extensively about the legacy of slavery.

Oliver Cromwell's statue outside Parliament was put up with private money

"I think it is a process, rather than the actual removal, starting a debate about collective values. Statues are lightning rods, symbols of the prevailing values of the society. When those values are not shared a debate needs to be started."

No-one would suggest the retention of a statue of Hitler, Dresser notes. But for many other statues the argument is far less clear-cut. And there is an argument that removing statues has the potential to harm our understanding of history.

"I do also take the point that if you look at many of the people celebrated in statues, they have been responsible for death and destruction," says Dresser. "Do we start taking them all down?"

People might not want to take their cue from the medieval Christians who gleefully melted down bronze equestrian statues of pagan Roman emperors and reused the metal. The one such statue to remain - that of Marcus Aurelius - was spared the furnace only because it was wrongly thought to depict the Christian Emperor Constantine.

Dresser suggests there is another way for more recent statues to be handled. To take the example of Colston in Bristol, the current positive plaque on his statue could be replaced by one that made clear that he was involved in the slave trade. Thus a debate could be started. "It's better on the whole to keep the statues but to recontextualise them."

The Voortrekker monument in Pretoria, South Africa

While the statues of Rhodes may be disappearing from South Africa, the giant Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria has remained and - despite its background of Afrikaner nationalism being associated with the later rise of apartheid - been tolerated as a slice of history, external and an opportunity to discuss the wrongs as well as the rights of bygone eras.

Other debates over statues may soon follow the same subtle path.

Who was Cecil Rhodes?

Imperialist, businessman and politician who played a dominant role in southern Africa in the late 19th Century, driving the annexation of vast swathes of land

Born the son of a vicar in Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, in 1853, first went to Africa at the age of 17; grew cotton with his brother in Natal, but moved into diamond mining, founding De Beers, which until recently controlled the global trade

Rhodes's bequest continues to finance scholarships bearing his name, allowing overseas students to come to Oxford University; most famous of these was probably Bill Clinton

Controversial even in his own time, Rhodes backed the disastrous Jameson Raid of 1895, in which a small British force tried to overthrow the gold-rich Transvaal Republic, helping prompt the Second Boer War, in which tens of thousands died

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.