A Point of View: Who should sit in the House of Lords?

- Published

Many people think that the House of Lords needs change but nobody can agree how or even why. Tom Shakespeare comes up with his own proposals for Britain's second chamber.

When I was a schoolboy, I memorized the Gettysburg Address for a declamations competition. Thirty years later, I have forgotten most of it, except for Abraham Lincoln's memorable phrase, "that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom - and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth". To me, this summation is not mere rhetoric. It outlines the principle of democracy to which we should aspire, and which both the United States and the United Kingdom often fail to uphold. It's a new year, which is a good time for new births and radical changes. Next week, I'm going to discuss 21st Century patriotism, but today I want to talk about Parliament.

The House of Lords reform debate has been going on for more than a century. The Blair government made a good start by getting rid of most of the hereditary peers, but then bottled out, leaving the upper house as a wholly appointed chamber. Nick Clegg put forward a reform bill in the Coalition government, but it was blocked by Tory backbenchers. A minor tweak in 2014 allowed members to resign, but despite this, the Lords has become so bloated that it is now the only upper chamber in the world that is larger than the lower house. In size, it is bigger than the Supreme People's Assembly of North Korea, second only to the Chinese National People's Congress and hardly more democratic.

So far, so familiar. But did you know that David Cameron has appointed new peers to the Lords at a faster rate than any prime minister since life peerages began in 1958? Back in 1999, after Labour created the temporary settlement, there were 669 peers. Now there are 821 - some 236 of whom were appointed by Mr Cameron. The House of Lords chamber only seats 400 people, so there must be a lot of sitting on each other's laps. Compare this to the Canadian senate, which is also undemocratic and unelected, but at least its numbers are fixed at 105 members. The US Senate has 100, the Australians have 76.

Their Lordships' house is not just overcrowded, it's also very unrepresentative of the diversity of our country. It still contains 92 hereditary aristocrats and 26 Anglican bishops. Only 25% of the Lords are Ladies, if you see what I mean. The Upper House also fails to represent the wider United Kingdom, because it is so London-centric. London has more members of the House of Lords than the East Midlands, West Midlands, Wales, Northern Ireland, the North East and Yorkshire and Humberside added together. Another problem is the falling number of independent peers. Crossbenchers, those distinguished experts who contribute their knowledge to debates, were meant to make up 20% of the Lords. But just 23 were appointed during the last parliament.

Perhaps partly because they have been half-reformed, to remove most of the hereditaries - and thus have a tad greater legitimacy - the Lords have been flexing their muscles recently. The Lords have challenged the unwritten rules that limit their power - such as the Salisbury Convention that the House of Lords should not oppose the manifesto commitments of the elected government. This constitutional impasse makes finding a solution more urgent than ever. The answer is not to limit the powers of the Upper House, as David Cameron threatens, but to put it on a true democratic footing.

The principles behind reform should be clear by now. The second chamber should not be a rival to the House of Commons. That's why it should not be all elected, or else it would threaten the supremacy of the Lower House. It can't resemble a retirement home for ex-MPs or trades unionists, let alone a public school. There should be no possibility of buying a peerage with a huge donation to a political party. It needs to have a political balance, and above all, it needs to be independent.

So here's my solution. I propose a lean, mean senate of no more than 300 members. Let's get rid of the titles and those remaining aristocrats. A third of our new senate should be independent members selected, as now, from those with experience and expertise, but chosen by a transparent process of public appointment, not by the prime minister of the day. These experts could include doctors, scientists, philosophers, lawyers, artists and creative people, and religious leaders of all faith traditions. These crossbencher senators should serve a single term of 15 years.

Then one third should be politicians, appointed from party lists in proportion to their party's showing in the last general election, to serve for (a renewable) five years. This would achieve proportional representation of smaller parties, and would help break Tory-Labour dominance. Finally, I propose that the chamber be completed with a third of members who are ordinary citizens, 100 people selected at random from the electoral roll of the United Kingdom, in the same way as people are currently appointed to juries. By making the senate directly representative of the people, this would give the second chamber an important source of legitimacy.

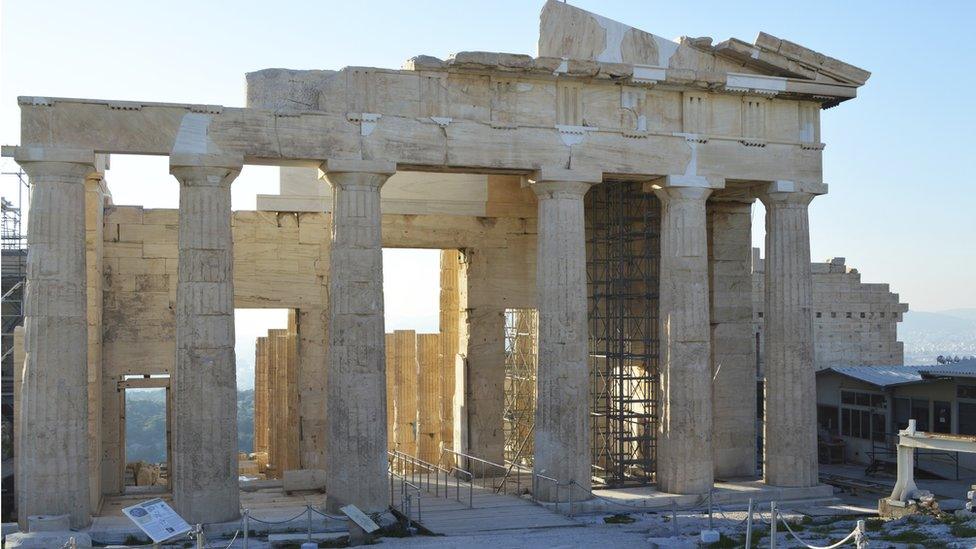

The site of ancient Athens's public assemblies

The idea is not new. Appointment by lot dates back to ancient Greece, when the Athenians used the lottery machine or kleroterion to select which of its citizens should govern the republic. The advantage of a random selection is that it generates a fair distribution across gender, age, ethnicity and region. It is invulnerable to corruption. It disrupts the party political machine, and has been proven to improve decision-making efficiency, external.

Lay people offer a fresh perspective and the wisdom of their particular experience, as demonstrated by our magistrates. The evidence from jury trials is that people take their responsibilities seriously and generally do a good job. A proper induction programme backed up with the services of the Parliamentary Library would enable these lay members to operate effectively. There is the great advantage that these individuals will be loyal to their own conscience, not to a particular party. Like all the senators, they should be paid an appropriate salary for the five years they serve.

Nobody would be forced to participate - if your number came up, you'd have the chance to say no. But those who did take their turn in governing the country would go back afterwards to their normal lives with a rich experience of leadership and deliberation, that they could then apply in their local neighbourhood or in their workplaces. I believe that this would transform public perception of Parliament, and give people a greater sense of ownership of the institutions of their nation.

If you are persuaded by my prescription, you may still be sceptical as to how this utopian state of affairs might be realised. After all, the Lords themselves are largely resistant to modernisation. In recent years, they have always voted for the status quo, a 100%-appointed house.

But revisions to the constitution can be achieved - we now have a supreme court, and Welsh and Northern Irish assemblies, and a Scottish Parliament, all of which innovations have invigorated our system. The Scottish Nationalists boycott the House of Lords, on the irrefutable grounds that it is undemocratic. They have no members currently, and nor have they put forward names for appointment as peers. It is entirely within the power of the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats to do the same. If all the opposition parties withdrew participation in the House of Lords, it would be unable to operate. And if they truly want renewal of our democracy, then this is how they should act. We cannot stumble on with an outdated system of governance. Like Abraham Lincoln 150 years ago, we need to take a leap into the future. Our descendants will only wonder why we did not do it sooner.

More from the Magazine

Ancient Athens operated a unique system of direct democracy in which all citizens could vote on laws themselves rather than electing representatives to do it for them. Could such a system operate in the modern UK, asks historian Paul Cartledge.

Would Athenian-style democracy work in the UK today? (January 2015)

This is an edited transcript of A Point of View, which is broadcast on Fridays on Radio 4 at 20:50 GMT and repeated Sundays 08:50 GMT or listen on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.