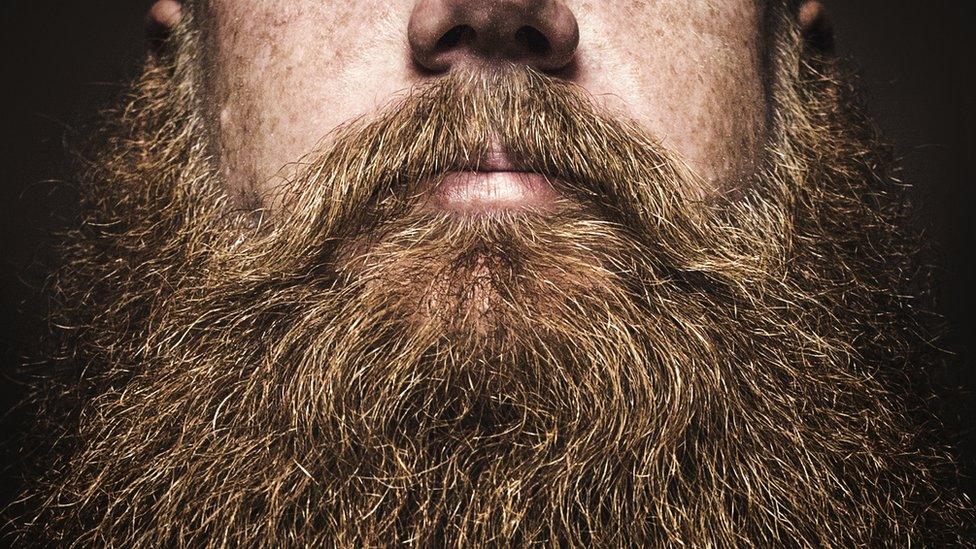

Are beards good for your health?

- Published

If you were in search of a new, disease-fighting antibiotic, where might you start? In a swamp? A remote island? Well, how about combing beards? Michael Mosley investigates.

On Trust Me I'm a Doctor we do experiments which sometimes throw up genuinely new science. In a previous series, for example, we discovered you can cut the calories in pasta by cooking, cooling and then reheating it.

That was a very pleasing result. But our most recent discovery, finding bacteria which appear to be producing a novel form of antibiotic, feels altogether more significant. What was particularly delightful was that they were found growing in someone's beard.

Beards, as you may have noticed, are back. The chin-strap, the goatee, the neck beard and the Van Dyke, they all have their fans. But with beards sprouting everywhere, like new grass in the spring sunshine, there has inevitably been a backlash.

Critics claim that beards are not only an irritating affectation but can potentially harbour unpleasant bugs.

So, what's the evidence that beards pose any sort of health risk? Pogonophobes, people who fear beards, had those fears confirmed by a recent study in New Mexico where they found traces of enteric bacteria, the sort usually found in faeces, in randomly sampled beards.

As one newspaper put it: '"Some beards contain more poo than a toilet."

But is this typical? A recent and rather more scientific study, carried in an American hospital, came to very different conclusions.

Find out more

Trust Me I'm A Doctor is on BBC Two at 20:00 on Wednesday 20 January - catch up on BBC iPlayer

In this study, published in the Journal of Hospital Infection, external, they swabbed the faces of 408 hospital staff with and without facial hair.

They had good reasons for doing so. We know that hospital-acquired infections are a major cause of disease and death in hospitals, with many patients acquiring an infection they didn't have when they went in. Hands, white coats, ties and equipment have all been blamed, but what about beards?

Well, the researchers were surprised to find that it was the clean-shaven staff, and not the beardies, who were more likely to be carrying something unpleasant on their faces.

The beardless group were more than three times as likely to be harbouring a species known as methicillin-resistant staph aureus on their freshly shaven cheeks. MRSA is a particularly common and troublesome source of hospital-acquired infections because it is resistant to so many of our current antibiotics.

So what's going on? The researchers suggested that shaving might cause micro-abrasions in the skin "which may support bacterial colonisation and proliferation".

Perhaps. But there was another more plausible explanation staring them in the face. That beards fight infection.

Unlikely? Well, driven by curiosity we recently swabbed the beards of a random assortment of men and sent them off to Dr Adam Roberts, a microbiologist based at University College London, to see what, if anything, he could grow.

Adam managed to grow over 100 different bacteria from our beards, including one that is more commonly found in the small intestine. But, as he quickly explains, that doesn't mean it came from faeces. Such findings are normal and nothing to worry about.

A brief history of beards

Alexander the Great reportedly banned his soldiers from growing beards, for fear that enemies would hold on to them in battle as they killed them

Hadrian (76-138AD) was apparently the first Roman emperor to grow a beard

At 17ft 6in long, Hans Langseth's beard may have been the longest ever - after his death it was donated to the Smithsonian, external in Washington DC

Beards were compulsory in Afghanistan under the Taliban - they were banned by Albania's communist leader Enver Hoxha (1908-1985), and more recently for a while in Turkmenistan

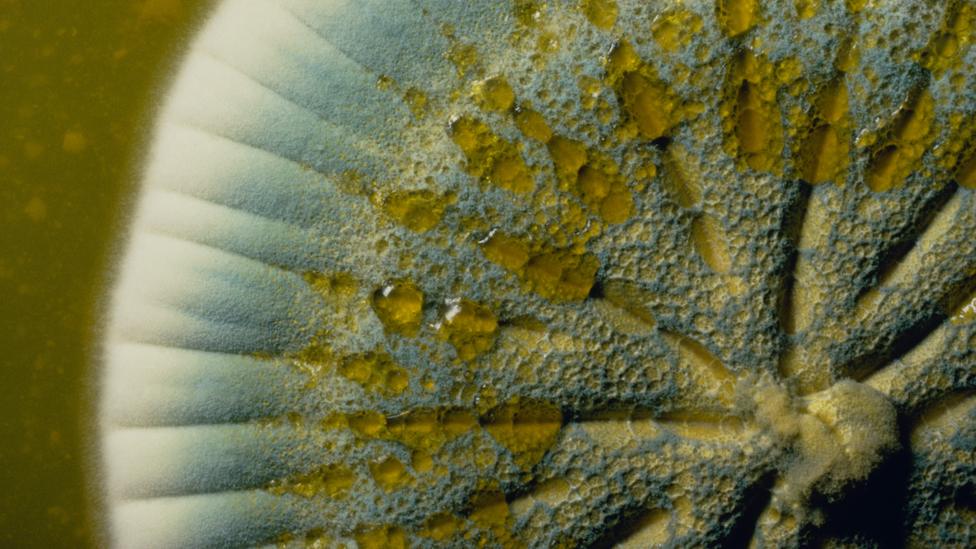

Far more interesting, in a few of the petri dishes he noticed that something was clearly killing the other bacteria. The most obvious suspect was a fellow microbe.

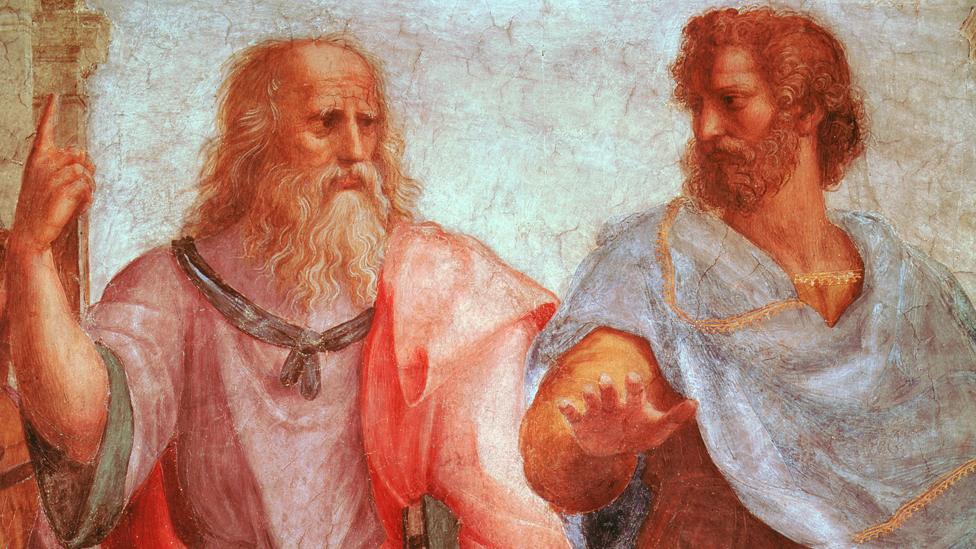

We see microbes as our enemy, but they clearly don't see us that way. Down at their level bacteria and fungi spend their time competing with each other. They fight for food, resources and space. By doing so, over millennia, they have evolved some of the most sophisticated weapons known to microbe-kind - antibiotics.

Penicillin was originally extracted from Penicillium notatum, a species of fungus. The microbe-killing properties of this fungus were discovered by Alexander Fleming when he noticed that a fungus spore, which had accidently blown into his lab from researchers further down the corridor, had killed some bacteria he was growing on a petri dish.

The fungus Penicillium notatum - is there something similar in beards?

So could our mysterious microbes be doing something similar? Killing fellow bacteria by producing some sort of toxin?

"Yes," says Adam extremely cautiously. "Possibly."

Adam indentified the silent assassins as part of a species called Staphylococcus epidermidis. When he tested them against a particularly drug-resistant form of Eschercichia coli (E. coli), the sort that cause urinary tract infections, they killed with abandon.

Purifying and properly testing a novel antibiotic is so expensive and has such a high failure rate that it is extremely unlikely doctors will be prescribing Beardicillin any time soon, but Adam is deadly serious about looking for replacements for our current stock of antibiotics.

Famous beardies ZZ Top

As he pointed out, antibiotic-resistant infections kill at least 700,000 people a year, projected to rise to 10 million by 2050. There have been no new antibiotics released in the past 30 years.

As well as our beardy findings, Adam's team have recently isolated, from microbes sent in by the general public, anti-adhesion molecules which stop bacteria binding to other surfaces. They think there may be potential for adding this to toothpaste and mouthwash, as it could stop acid-producing bacteria from binding to enamel.

Surprising, isn't it, what you can find in a beard?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.