The era when gay spies were feared

- Published

MI5 has been named the UK's most gay-friendly employer - but it isn't long since same-sex relationships were considered a threat to national security. How did attitudes change?

In 1963 the Sunday Mirror offered its assistance to the Security Service.

"How to spot a possible homo," ran a headline in the paper. Below this, for MI5's benefit, was a list of supposed signifiers of male homosexuality ("a gay little wiggle", "his tie has the latest knot", "an unnaturally strong affection for his mother").

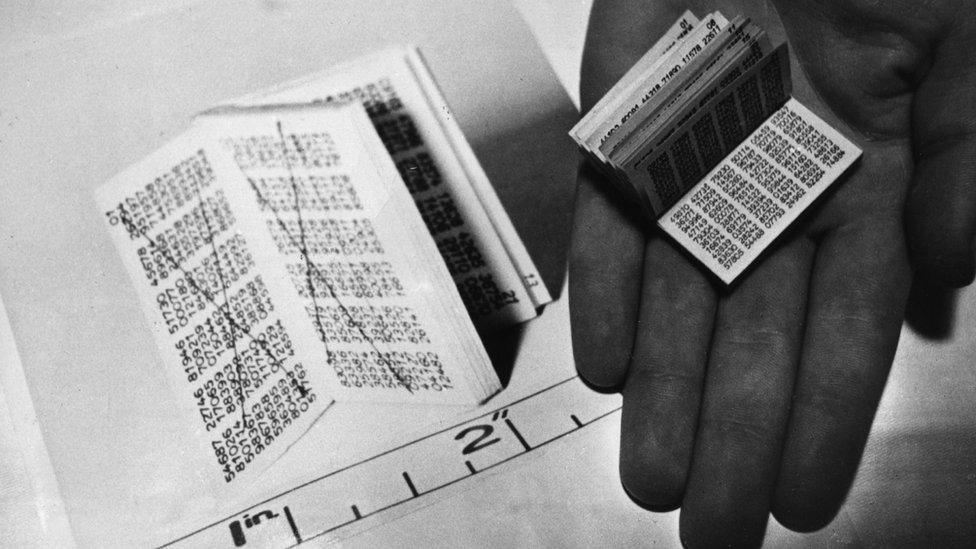

The pretext for this unsolicited advice - which now seems clearly offensive - was the case of John Vassall, a gay civil servant who spied for the Soviets under threat of blackmail. A gay man, the paper's reporter said, was a de facto security risk: "I wouldn't trust him with my secrets."

Fast forward 53 years and the service tops Stonewall's 2016 list of the 400 best places to work for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people. According to the Times, external, more than 80 of its employees belong to an LGBT staff network.

British civil servant and Soviet spy John Vassall shortly after his release from prison in 1972

And yet a ban on gay men and women serving in MI5, MI6 or GCHQ was in force as recently as 1991. The treatment of LGBT intelligence staff was exemplified by the case of pioneering codebreaker Alan Turing, who lost his security clearance after a conviction for gross indecency in 1952 and later took his own life.

A series of Cold War scandals featuring gay men meant homosexuality was linked in many people's minds with espionage and betrayal. As well as Vassall, who was caught in a honeytrap by the KGB, at least two of the Cambridge Five spy ring, Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt, were gay, while a third, Donald MacLean, was bisexual.

There was also Daily Telegraph Moscow correspondent Jeremy Wolfenden - son of John Wolfenden, who chaired the commission that recommended the legalisation of male homosexual acts - who was photographed by the KGB having sex with a man, and whom MI6 subsequently attempted to use as a double agent. He turned to heavy drinking and died in 1965 age 31.

Alan Bates played spy Guy Burgess in Alan Bennett's An Englishman Abroad

In the United States, Senator Joseph McCarthy's anti-communist campaign targeted scores of gay officials, explicitly linking homosexuality with subversion and Soviet sympathies, a process known as the "lavender scare". FBI chief J Edgar Hoover - himself widely believed to have been gay - used the agency to target dozens of gay government employees.

It was a period in which LGBT people risked losing their careers and their freedom if their sexuality was revealed. In 1953 President Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, which effectively ruled that gay people were security risks. Homosexual acts between men were illegal in Great Britain until 1967.

"Queer men were thought to be untrustworthy because of their queerness," says Allan Hepburn of McGill University, Montreal. "They were vulnerable to blackmail because the law offered them no protection."

J Edgar Hoover speaks to the Senate internal security committee

And yet nonetheless there was a double standard at stake. Though their conduct was not illegal, heterosexuals were hardly immune, external from honeytraps and blackmail - as evidenced by the cases of the Stasi "Romeo spies" sent to seduce West German women.

The Profumo scandal - in which the minister of war's mistress was found to have been sleeping with the Soviet naval attache - did not result in calls for straight men to be considered suspect, or prevent promiscuous heterosexuality becoming part of the James Bond mythos.

Indeed, the Guardian's former security editor Richard Norton-Taylor suggests, external that the secrecy imposed on LGBT people during this era may have made them more effective spies. "They could keep secrets, and tell lies."

This association between homosexuality and secrecy, furtiveness and potential treachery ensured gay characters were a recurring trope in Cold War-era spy fiction. John Le Carre's The Spy Who Came In From The Cold and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy include gay subtexts - made even more explicit in the 2011 movie adaptation of the latter.

Some have made the case that the British intelligence services appear to have been relatively accepting of homosexuality, if only compared with other parts of society that commonly persecuted LGBT people. Burgess's gay affairs were widely known in intelligence circles. As with fellow Cambridge Five member Kim Philby's heterosexual philandering, class and social status rather than sexual orientation appear to have been paramount.

According to Christopher Andrew's authorised history of MI5, gay men and women were in 1951 judged by the service when vetting public servants to be "maladjusted to the social environment", potentially "of unstable character" and vulnerable to blackmail. However, Andrew says MI5 was "relatively unconcerned" about gay civil servants so long as they "remained discreet". In 1965 MI5 resisted a view from the Treasury that homosexuality should be an absolute bar to any kind of public office that required positive vetting.

Jim Broadbent and Ben Whishaw in BBC drama London Spy

The legalisation of male homosexuality in 1967 meant the fear of blackmail could no longer hold. "You get rid of illegality and suddenly the fear of being blackmailed evaporates," says Christopher Murphy, lecturer in intelligence studies at the University of Salford, although it took public attitudes longer to catch up with the law.

The 2015 BBC espionage drama London Spy, which features a relationship between a young man and a male intelligence officer, is notable for the fact that their sexuality is not treated as particularly exceptional in itself. And when the news about MI5's place on the Stonewall list was revealed, the headlines were very different from those of 1963.

An era of secrets

The spy chiefs of MI6 and GCHQ are now public figures, but the secret intelligence service used to be so shrouded in mystery that revealing the name of a spy would land a writer in court.

Read more: The time when spy agencies officially didn't exist (Nov 2014)

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.