Flint water crisis: Living one bottle of water at a time

- Published

After months of delay and denial by state officials, action is being taken over lead in the water supply in the Michigan city of Flint. But residents say it's too little, too late.

While visiting nearby Detroit this week, President Barack Obama addressed the disaster that has left Flint's nearly 100,000 residents without safe tap water and at risk of lead poisoning.

"If I was a parent out there I would be beside myself that my kids' health could be at risk," President Obama said on Wednesday, adding that he had signed an emergency declaration over the weekend authorising federal aid for Flint.

Since the start of the new year, officials from multiple government agencies have announced investigations into the water crisis in Flint, a majority-African American city where over 40% of the residents live in poverty.

Federal Emergency Management Agency officers were dispatched to Flint last week and Michigan state troopers and National Guard members are on the ground handing out cases of bottled water.

But have these developments improved the daily lives of Flint residents?

Flint resident Melissa Mays: 'Our hair fell out'

"Not at all," says Melissa Mays, 37, a Flint mother who in recent days has seen long lines of vehicles snaking out of fire station parking lots where water is being given away. "They're throwing all these bottles of water at us like it's going to fix the problem."

The problem being that the people in Flint still can't safely drink, cook or brush their teeth with the water running through their pipes.

Mays, her husband and their three young sons have been living with a rationed water supply for a full year.

They buy as much bottled water as they can afford each month, up to $300 (£211) worth, and store the water on the counter next to their kitchen sink. They plan their days around how much they have left.

"If we're low on water, I can't make soup," Mays says. "It takes four bottles of water to boil macaroni."

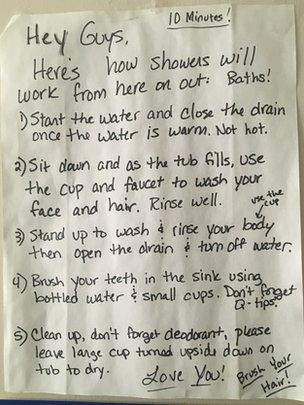

Melissa Mays' bathing instructions to her children

The Mays family unknowingly drank contaminated tap water for most of 2014. In that time, Melissa noticed that the water in their tub sometimes came out blue or yellow.

All five family members began to lose their hair and developed painful rashes on their arms and face.

"It burned," Mays recalls. "We'd ask questions and they'd say the water is just a little harder, it's fine."

Mays began to organise fellow Flint residents who were concerned about their water supply. For over a year, Michigan officials denied that anything was wrong, despite residents' complaints that the water was discoloured and tasted strange. State leaders were dismissive of residents' complaints about the water in their internal communications, too, as emails made public Wednesday by Michigan Governor Rick Snyder show.

This went on until October when, faced with mounting evidence, Governor Snyder admitted that the water in Flint was "a public safety issue." In late December, after a task force found Michigan's Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) was largely to blame for the crisis, the agency's director resigned.

But many questions still remain about the origins of the crisis and how it was able to go on for so long, unacknowledged.

Governor Snyder's office declined a request for an interview and did not answer a list of questions the BBC sent. In a statement provided to the BBC, the new MDEQ director Keith Creagh said that ensuring Flint residents have clean, safe drinking water is the agency's "foremost priority." Creagh also said the agency will test water in homes and schools and work with experts on "long-term solutions."

The water debacle began in 2014 when the city switched its water supply away from Detroit's water system, which draws from Lake Huron, and began to instead draw water from the Flint River.

Flint was in a financial state of emergency and this switch was meant to save the city millions of dollars.

But the water from the Flint River was more corrosive than Lake Huron's water and, for reasons still not fully understood, the new water wasn't treated properly to adjust for this. The pipes began leeching lead.

Flint switched back to Detroit's water system in October, but scientists agree the water in the city is still unsafe until proven otherwise.

"We still can't use the water and we don't know how long it will take before we can," says Flint's newly elected mayor, Karen Weaver.

Mayor Weaver sees the water crisis as two-fold - part public health disaster, part infrastructure crisis. She has said that replacing or fixing the damaged water system infrastructure could cost as much as $1.5bn.

The Flint river was far more corrosive than water from Lake Huron

The health implications for Flint residents are enormous.

"You can think about it as these children are drinking through lead-painted straws - the pipe is that straw," explains Dr Mona Hanna-Attisha, the Flint paediatrician who helped expose the water crisis by analyzing blood data from Flint children late last summer.

She found that children's lead levels had spiked since the city changed its water source.

Lead is a potent, irreversible neurotoxin and medical experts agree there is no safe level of lead in a child.

"It drops children's IQ points," Dr Hanna-Attisha says. "So imagine what this has done to an entire population. We've lost our high achievers and we have a lot more kids who may need special education or remedial services."

Angela Pineo, 29, worries every day that her 16-month-old son, Lennox, is among the Flint children who have been harmed. Pineo was pregnant when the city made the water switch. She drank Flint River tap water for the remainder of her pregnancy and while breastfeeding.

Flint Mayor Karen Weaver says her city's water is still not safe to drink

Pineo believes her son's speech and motor skill delays are due to his contact with lead. In the last six months, Pineo has made every lifestyle adjustment she can afford to keep Lennox from being exposed further to the poisoned water supply.

"I don't give him nearly as many baths as I used to," Pineo says. "I try to clean up with baby wipes as much as I can."

Despite the widespread attention and public outcry the disaster in Flint has prompted in recent weeks, Pineo doesn't think the situation has improved.

The switch back to Detroit's water system is the only tangible change Pineo can identify.

"Everything else is just words," she says.

- Published21 January 2016

- Published13 January 2016