Why Harris County, Texas, leads the US in exonerations

- Published

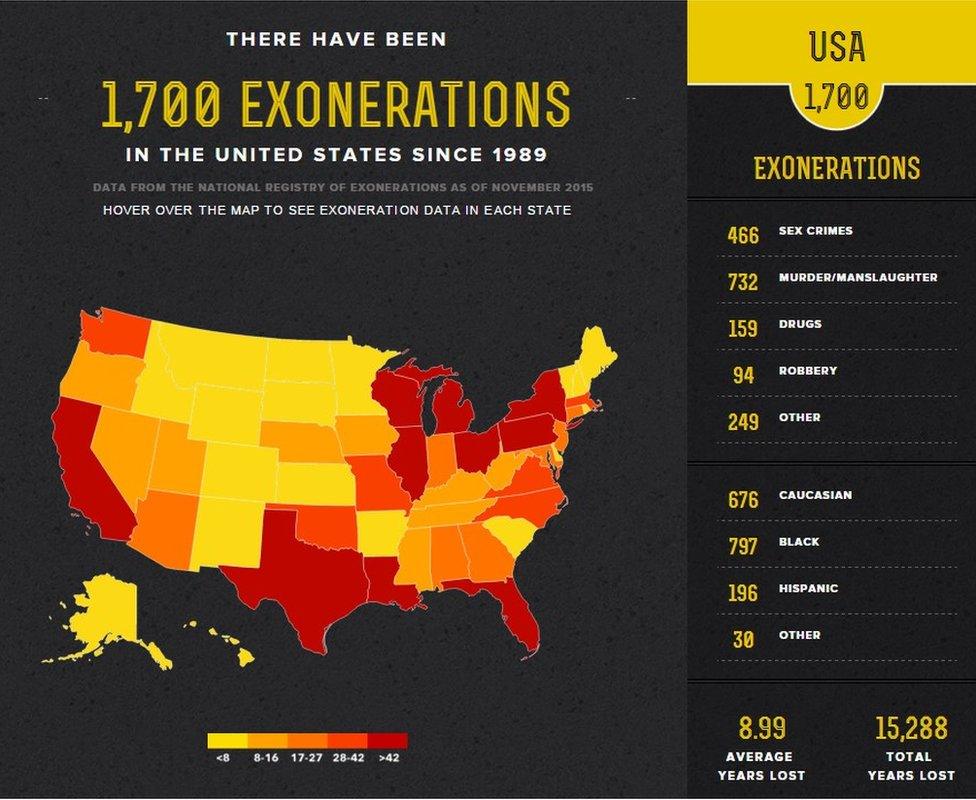

In 2015, there were a record number of exonerations in the US and for the second year in a row, a huge number of those came from Harris County, Texas.

A 19-year-old man is arrested for illegal possession of Xanax pills that turn out to be an insomnia medication. A cigar butt is confiscated from a teenager suspected of packing it with marijuana - but he didn't. A 25-year-old man is busted with 250 ecstasy pills that in reality are just over-the-counter antihistamines.

These may sound like small offenses, but they are just three of the stories of the 73 individuals who were convicted for drug possession in Harris County, Texas, and later found to be innocent.

This past year, there were a record-breaking number of exonerations, or criminal convictions reversed based on evidence of innocence, across the US.

According to the 2015 report, external from the National Registry of Exonerations at the University of Michigan Law School, 149 people were exonerated in 29 states after serving an average sentence of 14.5 years in prison.

Forty-two of those 2015 cases came from Harris County, the most from any single jurisdiction - the second runner-up is Brooklyn County, New York, with just 8. This is the second year in a row that Harris County - whose population is just shy of 4.5 million and encompasses the city of Houston - lead the report in sheer numbers. In 2014, it had 31, making it the exoneration capital of the US.

One would assume that the high rate of wrongful convictions would mean something terrible is happening in Harris County - but it isn't that simple.

"Because we were finally doing it right, all these exonerations came to light. That's why it's so dramatic," says Harris County public defender Alex Bunin.

The majority - 73 out of 76 total exonerations in Harris County since 2010 - were convictions for drug possession or sale. All the convicted defendants were later cleared through laboratory tests that showed the substances they were arrested for did not contain illegal drugs. This exculpatory evidence sometimes came back years after the person had pleaded guilty and served his sentence.

Compared to higher profile exonerations for rape or murder, these crimes can sound trivial.

But these convictions can have dramatic effects on people's lives, says Sam Gross, a University of Michigan law professor and the editor of the registry. Even more importantly, he says these cases reveal a larger truth about the way the US criminal justice system - where upwards of 90%, external of criminal cases are resolved through plea deals - functions.

"There are, no doubt, many thousands of people who plead guilty to misdemeanours all over the place, in every county in the country," he says. "There are thousands of people across the country who plead guilty to crimes they didn't commit."

The Harris County courthouse

The reason Harris County has so many exonerations is due to the work of its Conviction Review Section, an unit within the prosecutor's office tasked with re-examining questionable past convictions.

Back in 2014, not long after deputy district attorney Inger Chandler first took it over, she got a call from a newspaper reporter in Austin, Texas. He wanted to know why a slow but steady trickle of drug convictions were getting reversed, external, sometimes years after the fact, once lab tests showed no presence of the drugs in question.

When Chandler looked into it, she saw that these were cases where the defendant had pleaded guilty - a decision that shuffled their case to the bottom of the pile at the forensic crime lab. If the person had already pleaded, the logic went, there was no rush to test the sample at the already overworked and backlogged lab.

"It made perfectly good business sense, but if you're talking about issues of liberty it's a totally different story," says Chandler.

"I kind of freaked out and I went to my boss and said, 'This is crazy, this is taking too long.'"

Chandler made a series of procedural fixes, including making sure drug evidence is tested in the order it arrives. If it were found not to contain illegal substances, she streamlined the process by which her office notified the public defender's office. Those lawyers then file a writ to have the convictions reversed.

"Any case where the person is currently serving a sentence, I put them at the forefront," says Nicolas Hughes, the assistant public defender who handles the bulk of the exonerations.

A closer look at the case summaries show that the bad evidence came in many forms. Pills - often suspected Xanax - are simply misidentified.

Thirty-nine of the 73 total cases out of Harris County were charged based on faulty field test kits, usually a small packet of chemicals police carry that will change colours when an illegal substance is introduced.

Past investigations, external have shown that these tests will show a positive hit for all kinds of things, including Jolly Ranchers, vitamin powder, certain soaps - even just from contact with the air.

"Those tests are notoriously unreliable," says Gross. "They're not reliable enough to use at trial."

It was also noteworthy that 52% of the wrongfully convicted defendants were African American, though they make up less than 20% of the population of Harris County.

But the question that naturally arose was, why had dozens of people pleaded guilty to drug possession if they were in fact innocent?

The suspected explanations vary. Chandler believes most thought they really did have drugs, but in fact had purchased "turkey dope" or fake drugs. But there are other, more troubling explanations.

Crimes like drug possession are often low priority for prosecutors, particularly in a big place like Harris County, and the easiest way to dispense with them is through a plea deal.

Many defence lawyers complain that this is just a way to coerce indigent defendants who can not afford bail or a private lawyer into pleading guilty. Maintaining one's innocence and awaiting trial behind bars can sometimes take months.

"[If they plead guilty], they get to keep their job. They get to go home. They have immediate needs," says Hughes. "If you're in jail waiting, your whole life can go sour."

Natalie Schultz, a Houston defence lawyer, says she represented four people whose convictions were eventually thrown out. All four were homeless.

Even though they told her they were innocent, when the prosecutor offered them a plea deal with relatively short jail time, they snatched the chance to get out - even after she told them that she could not advise them to take the deal.

"Some of them would then say, 'OK, I'm actually guilty,'" she says. "I can't stop them."

The Harris County District Attorney's office has changed its policy on plea deals in these kinds of drug possession cases. Beginning in February 2015, they no longer offer defendants who are facing jail time a plea deal until definitive results have come back from the forensic lab.

Patrick McCann, a defence lawyer in Houston who has been examining this issue for some time, estimates that there will be at least one more banner year of exonerations for Harris County before the backlog of bad prosecutions is cleared and the new procedures start having an effect.

"I think they're doing an excellent job," he says of Harris County, while noting that not every prosecutor in Texas has taken this kind of aggressive approach to righting its wrongs.

"Lawyers are encountering a great deal of resistance from district attorneys' offices that simply don't seem to care about whether or not these cases get looked into."

Indeed, while Harris County may be a shining example, Chandler says some jurisdictions destroy drug evidence as soon as a defendant pleads guilty.

Texas has had 237 exonerations - the most per state since 1989

And she agrees that while these kinds of cases prove that the system pressures people into pleading guilty to things they didn't do, there are many other low-level convictions for which there is no easy forensic test to separate the good from the bad convictions.

"These drug cases create a unique set of cases where we can right the wrongs that happen," she says. "We don't have that ability in a lot of other cases."

Gross, the editor of the exoneration study, agrees.

"The small cases are the biggest issue in the area in my mind, by far," he says. "They're at the low end of the criminal justice system in the United States where almost everybody pleads guilty."