Gregoire Ahongbonon: Freeing people chained for being ill

- Published

For almost 30 years, Gregoire Ahongbonon, a former mechanic from Benin, has helped thousands of West Africans affected by mental illnesses, caring for them in residential centres run by his charity, the Saint Camille association. Above all else, he is determined to stop the practice of keeping mentally ill people in chains.

Aime has just come out of his room. He is taking tiny steps - his ankles held in leg irons.

The scene takes place in a small house in the city of Calavi, on the outskirts of Cotonou, the capital of Benin. Aime, 24, has a mental illness and his elder brother and sister have been looking after him to the best of their abilities.

"We've had to lock him up because he disturbs people and they come to our house to complain," says his brother, Rosinos.

"Sometimes he even attacks people in the street saying they've stolen something. He can't stop screaming, day or night. He can't sleep, so neither do we. I'm so overwhelmed by all this."

The family could not afford for Aime to be treated at the country's only state-run mental health institution, the Jacquot Public Hospital, where fees start at 20,000 CFA francs per month, almost half the average salary. Instead they gave him medication prescribed by the hospital - but after eight months they could no longer afford that either.

Aime had become calmer, but without treatment his illness quickly returned. Rosinos and his sister, Edmunda, were in desperation when Edmunda went to a lecture by Gregoire Ahongbonon, campaigning against the stigmatisation of mental illness.

Afterwards Edmunda asked Ahongbonon for advice, and Aime is now being taken to a centre run by the Saint Camille association in Calavi.

The association has more than a dozen centres across Ivory Coast, Benin, Togo, and Burkina Faso. They care for thousands of patients and charge very little.

Ahongbonon and his staff find homeless people, thrown out on to the street by their families, and give them a home. They also travel across West Africa on alert for reports of mentally ill people shackled or mistreated in remote villages. When they find such people they offer to take them in.

"Mental patients here are seen as possessed by the devil or victims of witchcraft," says Ahongbonon.

"That's the case in Africa in general, but in Benin it's even worse, because Benin is the home of voodoo, so it's even stronger here."

In Benin, when someone becomes ill, the family's first instinct is often to take the patient either to a traditional healer or to evangelical churches that claim they can heal the patient by praying for his soul.

When Pelagie Agossou's grandson, Judikael, became ill, friends encouraged her to take him to a church to have the "evil spirits" cast out. She rejected this advice, but tried just about everything else, including a traditional healer.

Judikael's problem was a form of schizophrenia, in which he heard voices telling him to take his clothes off and run out of the house.

"Once, after my child had run away from home yet again, a girl came and told me Judikael was wandering around the city in his underwear," says Agossou.

"So I dashed there but when he saw me he started to run… I ran after him and people started to chase him too, thinking he was a thief. And I was shouting 'No don't hurt him, he's my child.' I was so scared that the police would hurt him thinking that he was a thief."

She tried taking him to a private clinic but it was too expensive, and it was at this point that she visited a traditional healer, where she paid 80,000 CFA francs (£93) for a medicine that had no effect.

Find out more

A young woman is brought to a Saint Camille centre with her hands bound

Listen to Laeila Adjovi's documentary TheMechanic and the Mission for the BBC World Service on the BBC iPlayer

Read about the people "treated" for mental illness with hyenas

"I called him to say the medicine did not change anything," Agossou says, "and he replied, 'Well just stop giving it to him.'"

There are different types of traditional healer. A bokhonon deals with spiritual matters using divination to find and cast out curses, while the amawato is the herbal doctor.

"When the patient comes for the first time, I consult the divinities, and then I know if he broke a taboo, if he offended anyone, or if a spell was cast on him," says Nestor Dakowegbe, one of the most respected traditional healers in the country.

"It is much easier to treat a mental illness when it comes from a spell or the bad behaviour of a patient towards his ancestors - then you just have to restore balance. But when it is a hereditary illness or the result of a natural phenomenon like a head trauma for example, it becomes more complicated."

Nestor Dakowegbe is both bokhonon and amawato, so his remedies can consist of medicinal herbs, but also prayers to the gods, or actions that the patient has to take. He is proud of the knowledge that has been in his family for generations, and doesn't feel threatened at all by modern science.

"Some doctors already know me. When they have a patient and they see that their treatment from the white man's medicine is not doing any good, they often turn to me," he says.

"It happened many times, and we become partners. Sometimes, I also turn to modern doctors to come and support me on some difficult cases."

Gualbert Ahyi, one of the first trained psychiatrists in Benin and the former director of the Jacquot hospital, also believes that psychiatrists and healers can work effectively together.

He tells me the story of a woman suffering from depression, whom he took to a blind traditional healer, with beneficial effects.

"It took a great dose of humility for me, a skilled and trained doctor with all his degrees, to go and find a blind healer to help 'see' what was wrong," he says.

"Some healers say beware: 'You treat but we heal.' And they mean that after I have treated a patient, they must finish the job. They must restore balance, so that the patient becomes a social being again in his own culture."

But Gregoire Ahongbonon is sceptical about this approach.

"The perception that we have about Africa is that healers are more efficient than doctors at treating mental illness. But I've seen otherwise. Most patients start in churches and with healers, and so before they reach proper treatment their condition has deteriorated very badly," he says.

"So are healers really doing any healing? That's the question."

The Saint Camille association has no psychiatrist permanently on its staff in in Benin but it has occasional visits from psychiatrists in Europe, who come for a couple of weeks every few months.

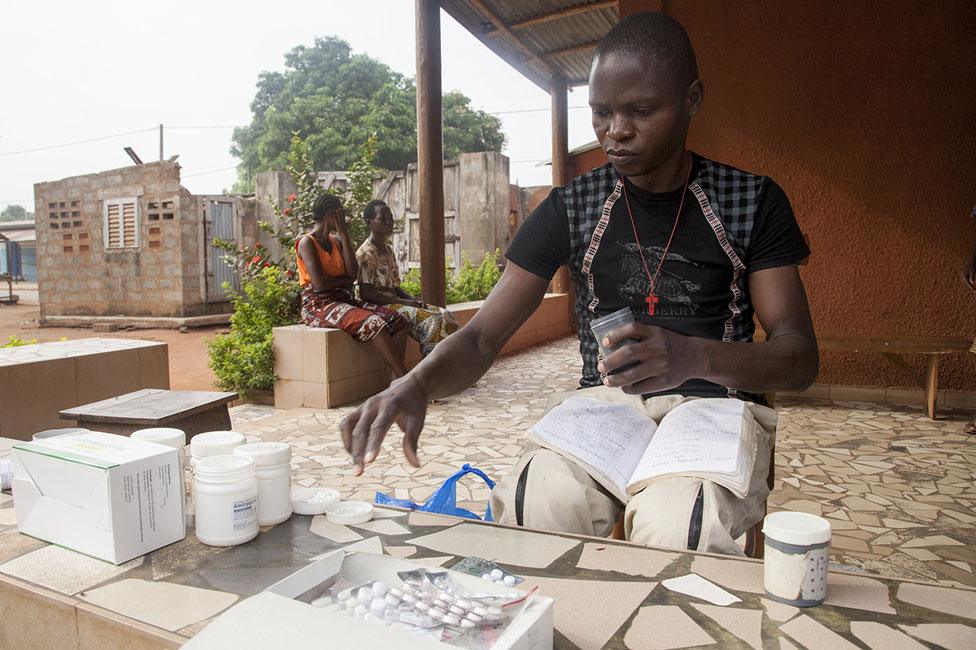

The priorities are a humane approach combined with low costs. Medication is paid for by the families of the patients, so the centres only use a small range of cheaper drugs. Many of the staff are former patients.

For Aime it has brought immediate improvements.

He is sleeping again, and has tried to walk out just once, though no-one knows if, when, or how Aime will recover - or as people say here, if he will be able to "find himself again".

Meanwhile, Judikael now comes once a month as an out-patient to get his injection. He has been treated at Saint Camille for almost a year, and takes one pill every day to silence the voices in his head.

He still struggles with some of the side-effects of his medication, which makes him sleepy and numb in the jaw and mouth, but he has started training as a tailor.

"Since I was a child I would always see grandma sewing, and I always found that interesting," he says, immensely grateful to his grandmother for bringing up him and looking after him during his illness.

Gregoire Ahongbonon recognises that not everyone is so lucky.

"We can't cure everyone because for many who come to us the illness is already chronic," he says.

"But we can help stabilise them, allow them to retrieve their dignity. My struggle is against the use of chains.

"In the third millennium the fact that we can find people in chains, and shackled to trees, I can't accept it, it has to stop. And I will say it again and again - as long as there is just one human being in chains then the whole of humanity is in chains."

In The Mind - a series exploring mental health issues

Explained: What is mental health and where can I go for help?

Mood assessment: Could I be depressed?

In The Mind:, external BBC News special report (or follow "Mental health" tag in the BBC News app)

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.