Could the ladybird plague of 1976 happen again?

- Published

The hot summer of 1976 saw swarms of ladybirds infesting towns and cities across the UK, with many people reporting being bitten by them. In the 40 years since there hasn't been a repeat, but could it happen again this summer?

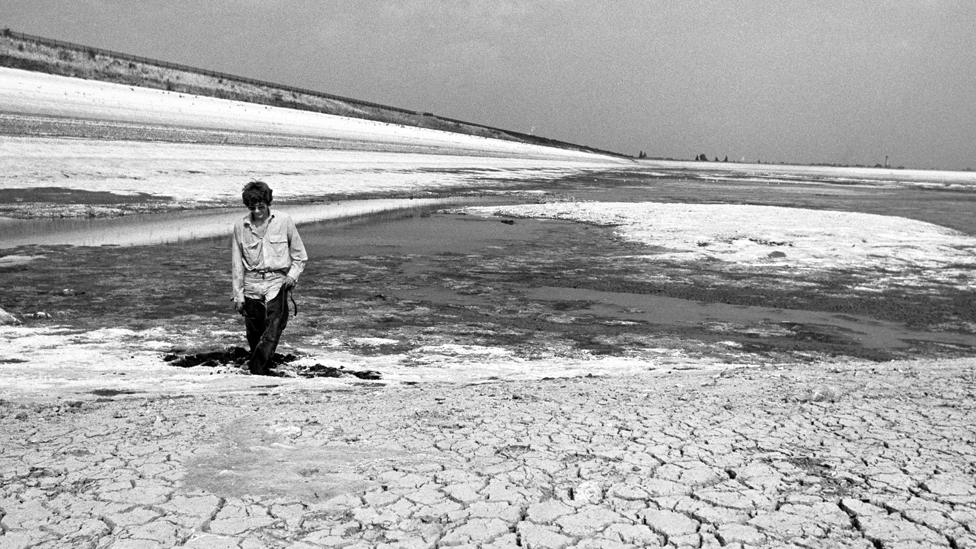

The drought of 1976 was unprecedented in its severity. Reservoirs dried up, as families queued to use standpipes to access drinking water. To titters worthy of a 1970s sitcom, Minister for Drought Denis Howell suggested people take baths with a friend.

And, with Milton Abbas, Dorset, and Teignmouth, Devon, having no rain for 45 straight days, the government warned some industries might have to close down because of water shortages.

Reservoirs dried up as a result of drought in the summer of 1976

But the heat wasn't the only seemingly apocalyptic event to hit Britain that summer. A plague of starving seven-spotted ladybirds besieged villages, towns and cities. The British Entomological and Natural History Society has estimated that 23.65 billion of them were swarming on the southern and eastern coasts of England by late July.

Brenda Madgwick, who spent some of the summer on holiday on Kent's Isle of Sheppey, remembered that "everywhere one put one's foot, it was thick with ladybirds, external. The posts along the sea-front holding up the chains were completely smothered.''

The ladybird population explosion happened at locations nationwide. "They were all over the place, on every pavement, and at times it was impossible to take a step without treading on them," recalled Frank Haiste of Leeds. The pool at Ruislip Lido in Middlesex was covered with dead ladybirds, deterring all but the hardiest swimmers.

The bugs, usually liked by gardeners because they eat aphids, a class of plant-sapping pests that includes greenfly, became briefly hated. They reportedly started biting humans, particularly by the seaside.

Simon Leather, professor of entomology at Harper Adams University, thinks changes to cereal production in the 1970s could have encouraged an increase in aphids, external, particularly the release of Maris Huntsman wheat - which they liked eating - in 1972. The main concern among agricultural scientists at the time was to prevent crops being ruined by fungi - not potential destruction by insects - he says, adding: "These days, people are much more aware of the importance of insect-resistance."

In 1976 a warmer than average spring saw larger than usual populations of aphids, creating more food for ladybirds. But the hot, dry summer meant plants matured and dried early, leaving the aphids without food. Their population collapsed in late June and early July. So hungry ladybirds moved on in their billions, searching for nutrition.

Swarms built up in coastal resorts as they got stuck by the sea, says Helen Roy, of the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. When well-fed, ladybirds are able to travel up to 120km (75 miles), flying at altitudes of more than 1,000m above sea level, allowing them to travel abroad. But by now they were too hungry and tired to go any further.

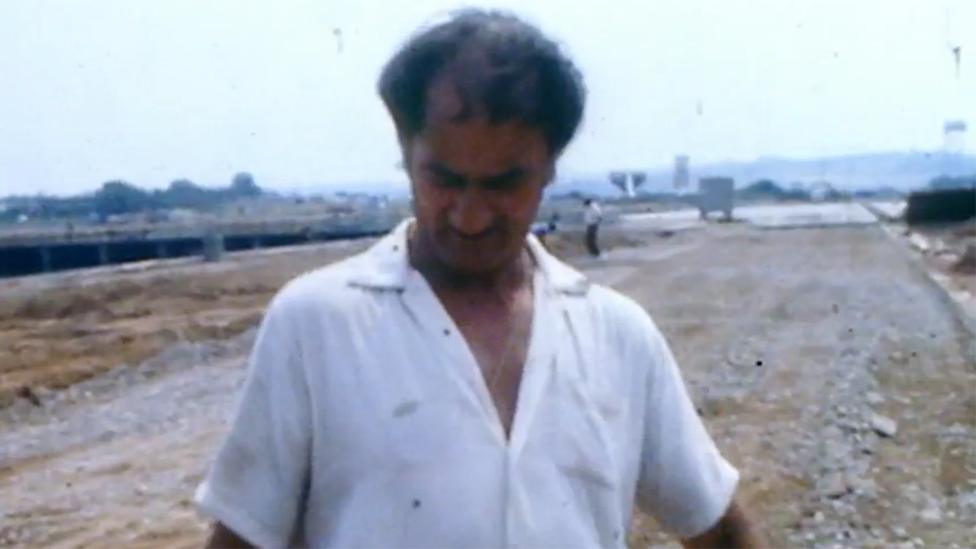

There were reports of ladybirds biting people

The attacks on humans happened as thirsty ladybirds tried to rehydrate using holidaymakers' sweat, says Roy. "They were also said to be attracted by people's ice creams," Roy, who co-runs the UK Ladybird Survey, external, adds, "because they would have provided a much-needed source of energy in the sugar they contained."

But Ian Rotherham, professor of environmental geography at Sheffield Hallam University, says it's "unlikely" the swarms went from inland Britain to the coast. "They don't tend, on a hot summer's day, to decide they want to go to Bridlington, or wherever, to cool off for a bit," he adds.

Rotherham thinks the migration was more likely to have been by ladybirds coming north from continental Europe, who landed on the beaches of southern England.

Whatever the cause, after the swarms subsided, New Scientist magazine predicted that another fine, warm spring and summer the next year could mean "two or three times as many" as the year before. But April, May, June, July and August 1977 were cooler than in 1976 and the ladybirds - known as ladybugs in the US - didn't come.

Explosions in populations typically happened "about once every 15 years" during the 20th Century, according to the British Entomological and Natural History Society, but not after 1976. By 1996 it reported the "longest period without an explosion this century". The year 1990 had provided conducive weather conditions, but a parasite destroyed many ladybird pupae - the stage of the bug's development between larva and adult.

The plague still hasn't returned, at least not nationally, although surges in aphids in Norfolk in 1979 and 2009, external saw outbreaks of ladybirds.

More on ladybirds

There are 46 species of ladybird in Britain

The harlequin ladybird (pictured above), which invaded the UK from France, has the potential to jeopardise many of these

Ladybirds have been introduced in Australia and California for pest control

They have many regional names, such lady-cows, may-bugs, golden-knops, barnabees and the bishop-that-burneth

So is there any chance of a repeat this year of what happened in 1976? "Never say never," says Leather. "Ladybird populations do seem to be in decline, but it depends on what farmers and gardeners grow, what parasites might kill them and how many aphids they can get to eat."

Ladybirds tend to thrive after a consistently cold winter, says Roy. This is because warmer temperatures, and particularly fluctuations, cause their metabolic rate to rise, burning off more stored fat and causing more deaths. The mild winter so far this year tends to suggest no 1976-style population explosion is imminent.

"It's very difficult to predict populations," says Roy. "It relies on a sort of perfect storm, with the weather conditions, including a cool winter and a hot, dry summer, and food sources being aligned."

In the UK, native species of ladybirds have come under threat in recent years, with the invasion from France by the harlequin ladybird, external, which eats them as well as aphids. But the seven-spotted variety, which tends to settle on plants, is one of the less vulnerable, as harlequins prefer to live on or near trees.

During another ladybird boom, in 1869, the Times reported that accumulations by the marketplace in Ramsgate, Kent, had resulted in men "shovelling them down the large grating into the sewer. So thickly were they spread over the ground that the streets seemed covered with red sand."

It's enough to make the flesh creep for those old enough to remember what happened in 1976, but it must be remembered that ladybirds are an important part of protecting the UK's food supply.

"Whatever happens, we should acknowledge that ladybirds aren't a pest but a hugely efficient way of reducing pests," says Roy. "They can eat up to 60 aphids a day, which is a real boon to gardeners and farmers. They're really quite marvellous creatures."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.