Germany's Syrians now waiting for their families

- Published

More than a million migrants arrived in Germany last year, after the country threw open its doors to those fleeing the conflict in Syria. Many who arrived hoped that their families would be able to follow afterwards - but they are now finding the process is slow and difficult.

"Wir schaffen das!" cried Angela Merkel last summer - "We can do this!" But her open-door policy has become mired in controversy, especially after the incidents in Cologne on New Year's Eve, when women were assaulted by gangs of men, including some asylum seekers.

The German parliament is now passing laws that will restrict refugees' ability to bring family members to Germany. However, because the situation in their home country is so perilous, many Syrians may yet be reunited with their families.

Here four explain their predicament.

Mohamed and Noor

Mohamed with pictures of his son, one of the many thousands injured in the conflict

"I would never ever have come to Germany if it wasn't for my son," says Mohamed. His nine-year-old boy lost his leg in a bombing raid on their village in Syria. It could have been even worse - Mohamed says his nephew and 15 other children died in the same raid.

The former chef says he was drawn to Europe to give his son better access to healthcare, but he was forced to leave him behind with his wife and youngest daughter. "I would have taken them with me, but the journey would have been far too exhausting for a two-and-a-half-year-old and a disabled child," he says. "My daughter was the only one I could take."

Mohamed and his daughter, Noor, who is 16, nearly didn't make it themselves - they almost drowned as they approached Greece, but they were fished out of the water.

Mohamed rarely smiles. His life is filled with anxiety as he tries to figure out how to get the rest of his family out of Damascus, and bring them to Germany safely and legally.

Almost every day, he spends hours queuing in the cold outside the Office of Health and Social Affairs - better known in Germany as Lageso - where he and other asylum seekers must go to collect papers and welfare payments.

He likens the process of gaining entry to the office, which involves getting your hand stamped, to the way sheep are corralled and branded in Syria.

And he complains that the officials are rude and unhelpful, sometimes yelling at him in German, which he does not understand. "I swear to God there was one official who made me feel I was being interviewed by the secret police in Syria," he says.

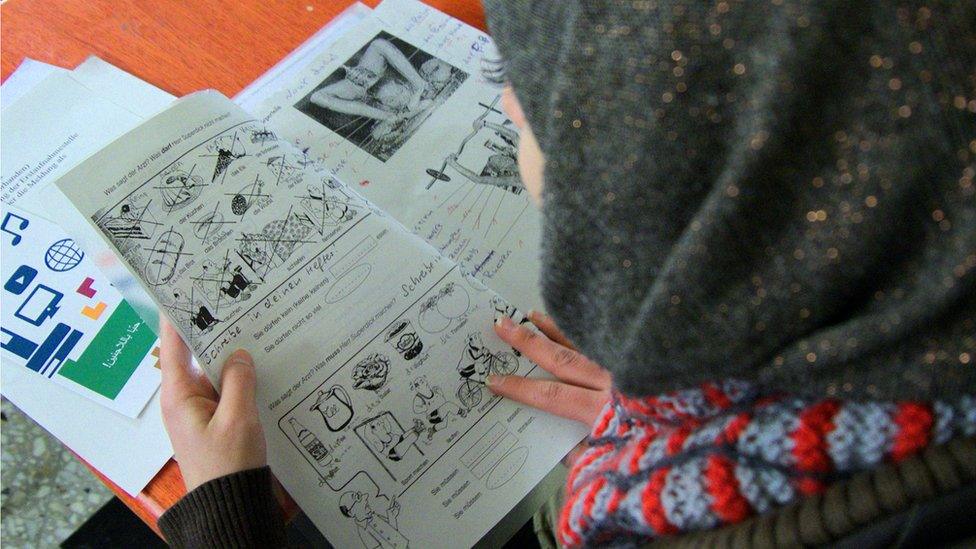

Noor studying German - she says she can find it difficult to concentrate in the block where they are staying

Mohamed is still awaiting the paperwork giving him official status as a refugee and permission to stay in Germany for three years, but the amount of time this takes seems to vary enormously.

Once he gets leave to remain he will be able to put in a family reunion application . But this can take up to a year to process, he has been told.

However Mohamed has also learned that if his wife obtains a letter from a doctor in Syria, saying that his son is in need of treatment abroad, there may be a way to speed things up.

"I came to get him out of there!" he says, his voice filled with anguish. "If it takes too long, I'd rather go back and die with my family than stay away and leave them alone there!"

Father and daughter share a single room in a large office block on the edge of Berlin. Noor has been enrolled in a German high school - she says she wants to study to become a pharmacist - but there is nowhere in their makeshift accommodation for her to do her homework.

Ahmed Shwine

Ahmed Shwine believes his family can be happier and more successful in Germany than in Turkey

Ahmed, who is in his 50s, decided to uproot his family from their home in Aleppo when his sons reached conscription age. "I thought: 'Shall I really give my sons away to fight their brothers?' What for? The current regime? The opposition? It is all the same! It means that my children would die for nothing."

Now, all six of Ahmed's children live in Ankara in Turkey . The two eldest, who are 17 and 18 years old, should be in university, he says, but instead they are forced to work, to support the rest of the family.

Although he appreciates the support his family has received from Turkey, he can't see a good future for them there, so he has come to Germany. He hopes his wife and children will be able to join him soon.

His emergency accommodation is in office building once owned by the Stasi, the notorious secret police force that operated in East Germany. For two months, he slept on the floor with no cushioning, before a departing asylum seeker gave him a mattress.

The migrants live cheek-by-jowl, but everyone tends to get along. "We didn't walk through seven countries to fight each other here," he says.

He seems to take everything with a wry smile. He asks a lot of questions and gives his opinion to anyone who will listen.

Like Mohamed, he is still waiting for his official refugee status and he has no idea when it will come. And he also regularly goes along to Lageso to submit or collect paperwork or payments.

Asylum seekers queuing outside Lageso, which is notorious for long delays

He was recently shocked to see security workers outside the office beat up a fellow asylum-seeker.

"In my opinion, 90% of the German people are amazing, wonderful and kind human beings," he says. "I owe them a lot. So why do the remaining 10% - that I don't count as Germans - have to work in a position like this?

"My children one day will come here and be German citizens. That is a fact, whether these 10% like it or not. So why don't we all get used to it now, and all of us respect German law? Or do these 10% not want to respect their own law?"

Find out more

Amy Zayed spoke to asylum seekers in Berlin for the World Service documentary Die Klassen: How Syrians Adapt to Life in Germany

Listen online from 04:00 GMT on Sunday 21 February, or get the Documentary podcast

Ebtesam

No matter how difficult her situation, Ebtesam is always ready with a smile

Ebtesam's name means "smile" - and there is always a smile on Ebtesam's face.

Yet her life is full of worry. Her husband has Parkinson's disease, and he did not take any medication during their stressful trip from Syria. Now his condition seems to have deteriorated. "He fell down the stairs recently," she says.

While they wait for a decision on their asylum application, the two of them are living with his mother - who is also unwell - in a single room in a repurposed office block. The room is filled with stuffed toys and very little furniture. "We're OK here," she says.

Ebtesam, who is in her late 40s, says that because her husband and mother-in-law need rest, she spends a lot of time in the corridor, reading. She also cleans the communal kitchen and toilets, to save the authorities the trouble. "I think the Germans have helped us so much," she says. "We need to help them too, to make it work."

After her eldest son was imprisoned for rebelling against the Assad regime, she convinced him to come to Germany too.

He arrived in December, two months after them, following a spell in a refugee camp in Turkey. He came to Berlin but his mother advised him to go on to Hamburg, where she thought the authorities might be less stressed-out and over-worked.

Ebtesam's daughter lives with her husband in Norway and is planning to come to Germany in a few months' time. She may try to stay.

Ebtesam recently stopped wearing the hijab, since she found it odd to wear it in a country where most people don't. She loves fashion and art. "One day, and all this is done, when I can sleep with no worries, I want to do something to do with art," she says.

"Germany has become our second home. We will never be able to repay them! This country has embraced us and now we are Merkel's children! Germany's children!"

Ahmed

Ahmed - who didn't wish to be identified - is now searching for a new flat

Ahmed, who is in his late 20s, has been in Berlin for three months. It's not nearly as long as many other asylum-seekers, yet he has been lucky enough to receive refugee status already.

He was especially surprised - and relieved - by the speed at which his case was processed because he had lost all his documents in Macedonia, where he was imprisoned for a while on his way to Germany.

Officially, Ahmed's new status means he can stay in the country for at least three years. In reality, it means he will probably be allowed to stay for good.

His residency permit also means he can rent a house on the open market, and is entitled to benefit payments to cover the cost. He is eager to move out of the block where he has been housed alongside asylum-seekers from other countries - a cultural mix he says caused some difficulties.

Most importantly for Ahmed, his new legal status means he was able to apply for his wife and 18-month-old son to join him from Syria.

But their application for a visa had to be filed with the German embassy in Beirut. They recently made the treacherous journey to Lebanon from Aleppo - and then had to return to wait two or three months until the paperwork was ready, so that they can leave for good.

"Today they will go back to Aleppo - and you know Aleppo is the most dangerous city in Syria," he says. "I hope they will stay alive."

Amy Zayed spoke to asylum seekers in Berlin for the World Service documentary Die Klassen: How Syrians Adapt to Life in Germany. Listen online from 04:00 GMT on Sunday 21 February, or get the Documentary podcast.