Europe hates Trump. Does it matter?

- Published

- comments

A carnival float mocking US Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump was displayed in Duesseldorf last month

Invoking global opinion in the context of US elections is a fool's errand. Perfectly understandably, voters in Paris, Pennsylvania, really don't give a damn what voters in Paris, France, think about their political choices. And why should they?

This is America's choice, not anyone else's. How would British voters feel if Texans weighed in on Brexit? This time, however, the international reaction to Donald Trump is so forceful and so unanimous in its condemnation that it is worth drawing attention to. I do so well aware that recent history is replete with examples where the world's opinion of a US presidential candidate backfired against those same critics.

Back in 2004, Europeans assumed that their own well-publicised opposition to President Bush's Iraq war would make it harder for him to get re-elected. In fact, anti-Americanism had the opposite effect. It drove people to the president. "If those squishy Europeans hate him so much," the thinking seemed to go, "then he must be doing something right."

That same year, Britain's left-leaning Guardian newspaper ran a public campaign targeting a critical county in Ohio, external with a letter-writing blitz, urging people there to vote for John Kerry.

It was a bid to give foreigners a say in the US presidential election. Clark County was a swing district in a swing state; in 2000 Al Gore won the area by a narrow margin. But the Guardian's Operation Clark County backfired. It did indeed galvanise local voters, but it did so for Bush not Kerry. On election night, George Bush carried the county with 51% of the vote.

At the time, a local newspaper editor told the BBC that it was the well-publicised letter campaign that lost it for the Democrats. It will go down in history as one of the biggest fiascos in foreign meddling.

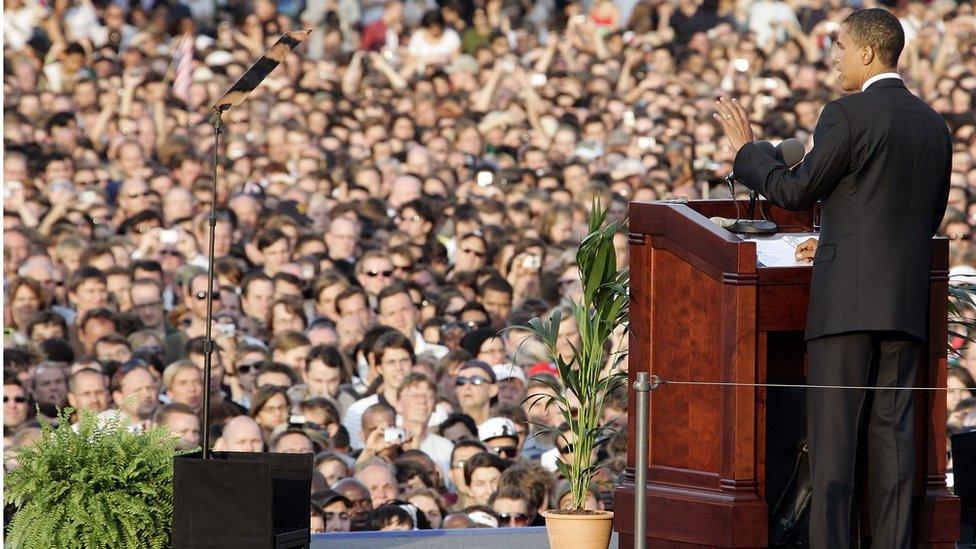

Crowds turned out in droves to see Obama in Berlin

In 2008 of course the world rallied firmly behind Barack Obama. Two hundred thousand people turned out to see the candidate in Berlin before the election. Italian trattorias started a roaring trade in Obama pizzas, a curious, un-Italian mix of ham and pineapple toppings.

We began to joke that France was so invested in the election it felt it should have a Paris primary. That time around, world opinion was on the side of the winner and American voters seemed to enjoy the rehabilitation of their global reputation.

So, what does the world make of Donald Trump?

Mr Trump has some admirers in Europe. A few on the extreme end of the political spectrum like his tough line on immigration. Jean-Marie Le Pen, the founder of the French National Front, said if he were American he'd vote Trump.

There are echoes of Trumpism in the nationalist parties of Britain, Denmark, Netherlands, Greece as well as France. The dissatisfaction with the status quo, the sense that middle-class and working-class people have been neglected by the existing political establishment, a feeling that politicians aren't honest with voters - you can find all that in the appeal of Europe's populists.

While the politics of Jeremy Corbyn, the socialist leader of the Labour Party, are the opposite of those of Donald Trump, the disillusionment that drives his supporters is not so different.

But the voices of support are drowned out by almost universal condemnation. When it comes to Trump, Europe is apoplectic. Fascinated, but appalled.

I'm sometimes asked by Americans what Brits make of Trump and the best analogy I can come up with is this.

Imagine if your much-respected but slightly annoying older sibling (the US) came home with a fantastically unsuitable date (Trump). Part of you is titillated but part of you is appalled, thinking, "Oh my God, this could go horribly wrong." After Super Tuesday, Europe is fast moving from the former to the latter.

Jean-Marie Le Pen says he's a Trump fan

Here's a sample of the public disapproval. Germany's Der Spiegel has called Trump the most dangerous man in the world. Britain's David Cameron says his plan to ban Muslims is divisive and unhelpful.

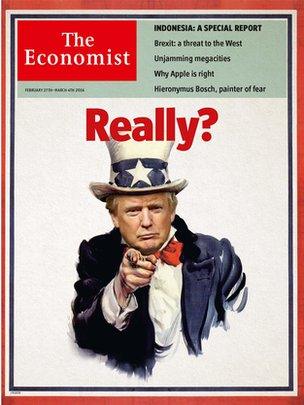

The French liberal newspaper Liberation has described him as a nightmare turned reality. JK Rowling tweeted that he's worse than Voldemort. A recent Economist cover has a picture of Trump dressed as Uncle Sam with just one word, "Really?" That pretty much sums up the mood of global elites.

Will the international reaction make a shred of difference to Trump's chances of getting nominated and then elected? 2004 would suggest not. Indeed you can easily imagine a scenario in which Trump's American supporters rally round their candidate even more closely because the world is against him, just as they did with President Bush.

If you like Trump, you're likely to shrug off French disdain - who cares what a bunch of cheese-eating surrender monkeys think? And if you don't like Trump, you're likely to see the criticism as a source of embarrassment - God, what does the world think of us?

What really matters is whether the 6-10% of voters in the middle of the American political spectrum, the people who actually decide elections here, are swayed by global opinion. And they may be, for two reasons.

This is a different time from 2004. For a start, Donald Trump is not yet president. As a candidate, he doesn't command the automatic respect imbued by the Oval Office.

Although America still feels under siege from Islamic extremism, American troops are not being killed in large numbers in Iraq and Afghanistan. Supporting Bush was in some ways a proxy for supporting those soldiers.

America rallies round the flag when its men and women are serving in combat in foreign countries. In a time of war, US voters didn't like their leader being criticised by foreigners.

What's more, that small percentage of American voters who sway elections tend to be more moderate. They often classify themselves as independents. So they may look at the way foreign allies view Donald Trump and feel it would damage America's standing in the world if he were president.

It's hard to know at this stage what impact foreign opinion will have in this race, but it's fairly clear the world is not going to suddenly fall in love with the man Republicans are rapidly choosing to be their candidate for the White House.