How much diesel pollution am I breathing in?

- Published

People are increasingly being warned about the dangers of diesel pollution, but how much are we actually exposed to? Tim Johns tried to find out.

Waiting for my train one day, standing on the concourse, it occurred to me that there seemed to be rather a lot of fumes coming from the idling diesel engines.

How much diesel pollution was I breathing in?

I decided to undertake an experiment for The Jeremy Vine Show on BBC Radio 2 to find out how much I was being exposed to on a daily basis, in different locations and on different modes of transport.

The environmental health researchers at King's College London lent me a portable device to monitor pollution. It measures black carbon particles from the combustion of diesel fuel. The higher the reading, the less healthy it would be.

This device takes a reading of black carbon particles

Diesel cars have been extremely popular in the UK, in part because they produce less carbon dioxide than petrol cars. But in 2012 the World Health Organization reclassified diesel pollution as a "definite carcinogen". It can cause lung cancer and may even cause tumours in the bladder.

"For all sources of air pollution the value which we believe is associated with early mortality is the equivalent of 29,000 deaths per year in the UK," says Prof Frank Kelly, head of the Environmental Research Group at King's College. "And diesel tends to produce more pollutants than, say, petrol would. So it is quite a sizeable public health challenge."

A recent study put that figure even higher - blaming air pollution for 40,000 early deaths every year in the UK. Again, researchers cited diesel as the major villain.

The official advice is that everyone should try to limit their exposure to diesel fumes. But just how much are we exposed to on a daily basis?

Radio 2, where I work, is based in central London, but I commute from Bedford, 50 miles to the north. I cycle to the train station, catch a diesel train to London, and then cycle to the office.

Across a week I used the device - a small box with a protruding rubber tube which sucks in air - to gauge my exposure to diesel pollution.

I monitored my journeys and, for comparison, I also took readings when driving in Bedford town centre, while taking a cab journey and riding the Underground in central London, and while sitting in the office and at home. On one day I caught a different train to work - an electric one.

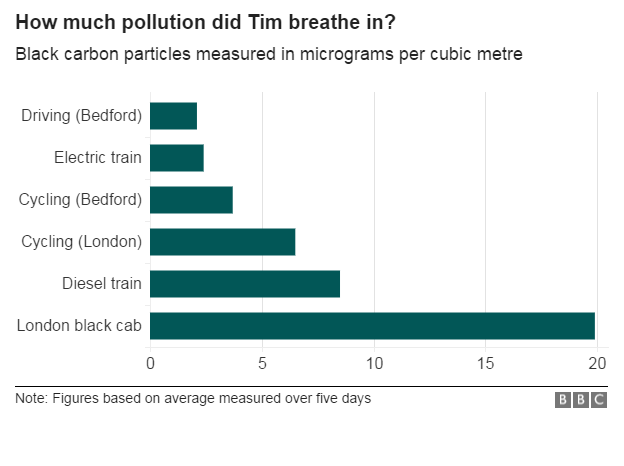

My monitoring device took a reading every minute and I took averages across the week for my different types of transport. The results were measured in micrograms per cubic metre. The lower the number, the less diesel I was being exposed to - no official guidelines exist to specify how much is too much. I wore a GPS watch too, tracking my movements.

Slow-moving traffic is one of the worst environments for diesel pollution

I was told to expect readings of between 0-3 micrograms per cubic metre if indoors and away from traffic. And that's just what I got for my work office at 0.8 and my home which registered 1.4.

Walking around in Bedford my readings rose to 1.7 and a Saturday afternoon spent driving around town gave me a reading of 2.1.

The researchers at King's College say one of the worst environments for diesel exposure can be when you're sitting in your car in slow-moving traffic (although some modern cars are now excellent at filtering out pollution).

On my commute, cycling to and from the train station in Bedford gave me a reading of 3.7.

Cycling to and from the office at the other end in central London, my exposure rose to 6.5. That's a stark reflection of the far higher level of traffic in central London and other major cities.

But my biggest surprise was on my train journey. Diesel-powered trains like the one I commute on are found on many major routes across the UK. The East Coast Main Line north of Edinburgh, the Great Western route through to Cornwall, and London services to Sheffield and Nottingham are just some examples.

The average reading I got on-board my air conditioned train was 8.5. A researcher from King's College conducted an experiment to mirror mine on his train journey from London to Exeter and came out with similar results.

My time spent standing on the station concourse at London St Pancras, waiting for my train, produced a reading of 13.2.

So it turns out that during the 80 minutes I spend sitting still on a train every day I am being exposed to more diesel fumes than when I'm walking or cycling down a street full of traffic in London. On the day I took an electric train instead, my reading was only 2.4.

My highest reading of the week came from a journey I took with a black cab in the capital. We spent most of the journey crawling in traffic - the windows were down - and I got a reading of 19.9.

Driving a car in slow traffic around a big city appears to remain the worst thing you can do if you want to limit your exposure to diesel fumes. The researchers at King's College confirm that my readings were similar to previous experiments they'd conducted.

People may find it hard to avoid long journeys on diesel trains. But Kelly says: "I would make doubly-sure that when I was not on a train that I was being exposed much less.

"If I was a diesel train driver I might be worried. The question is whether those readings found in the passenger cabin would be similar to what the driver is exposed to."

Dr Benjamin Barratt is a lecturer in air quality science. He took a look at my train-journey readings.

"We don't yet know the long-term health impacts of these short elevated periods of exposure to diesel pollution experienced while travelling, so the general advice is to try and minimise your exposure. The choice of train and bike over car, taxi or Tube is a good one."

There's one other astonishing measurement I recorded which I haven't mentioned yet. On the London Underground my device gave me a reading of 77.8.

But this wasn't caused by diesel fumes - other particles found underground can skew the reading.

"The device measured 'black particles', which, above ground would primarily be black carbon from diesel," says Barratt. "But below ground most of it is oxidised iron coming from the tracks. It's well known that the Tube is a dusty environment, but what is not well known is how toxic the specific kind of particles that we breathe while travelling underground are."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.