Is Coventry about to have a moment of glory?

- Published

Surrounded by a ring road and built in concrete, Coventry has a reputation for car manufacturing rather than concerts. But could this be the next UK City of Culture?

On the night of 14 November 1940 the city of Coventry suffered terrible damage in a German bombing raid. More than 550 people died and many of the buildings in the city were destroyed.

What the Luftwaffe started, the post-war planners completed, and little now remains of Coventry's splendid medieval centre - the old street plan was swept away, to be replaced by enormous pedestrian precincts.

Later, as befitted the birthplace of the British motor industry, the whole lot was imprisoned in the looping embrace of a spectacular ring road.

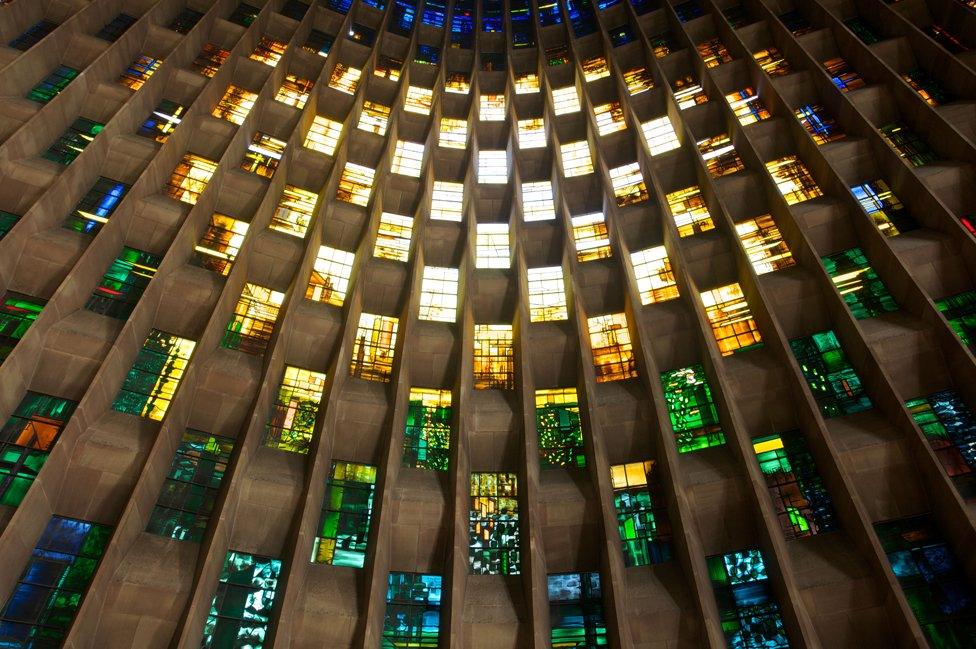

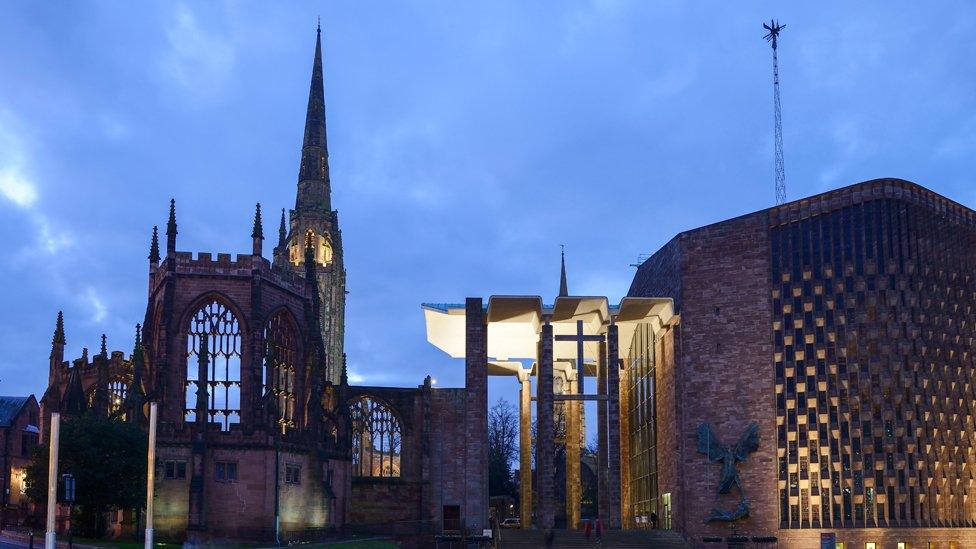

The city's burnt-out cathedral was left as a monument to the bombing and a modernist replacement designed by Basil Spence was built alongside. It boasts a collection of specially commissioned art, including a huge tapestry by Graham Sutherland and stained glass windows by John Piper, two of post-war Britain's greatest painters.

There is plenty of culture in Coventry, it is just that nobody outside the city seems to know about it. That is something those backing its bid to be UK City of Culture in 2021 hope to remedy.

"It's a place that is undervalued, underrated, unloved and perhaps misunderstood," says Andrew Dixon. A professional arts administrator and enabler, fresh from helping Hull to win City of Culture status for 2017, he is Coventry's bid adviser.

He points out that Coventry has a proud record of cultural innovation. "It invented Theatre in Education 50 years ago. Warwick University was the first place that studied film in the UK. It's a place where artists have been reinventing the city for many centuries."

Ian Harrabin, who helped form a trust to rescue Coventry's medieval Charterhouse just south of the city centre, says even local people seem to have forgotten about Coventry's considerable heritage. He thinks the bid could do wonders for its reputation. "It's a fantastic fillip to civic pride. It's giving an external image to investors, to tourists, to people sending their children to the university, that Coventry is this place of heritage as well, that it's a nice place to live and a nice place to work."

Coventry's medieval Charterhouse

The trust has an ambitious scheme to revitalise not just the Charterhouse and its rare medieval wall paintings - turning the house and its garden into a "stately home" in the heart of the city - but also the playing fields alongside it, and the grand 19th Century cemetery across the road designed by Joseph Paxton, the man who built the Crystal Palace.

At the city's Belgrade Theatre, director Hamish Glen remembers the transformative impact on Glasgow of being European City of Culture in 1990, and hopes for something similar in Coventry.

Coventry's reputation isn't just a result of that wartime bombing. In the years since, most of the car factories and component suppliers that made Coventry rich have shut - only Jaguar Land Rover and the London Taxi Company remain. There are empty shops in the city centre. Proverbially, Coventry is the place to which people are sent when their "friends" won't talk to them.

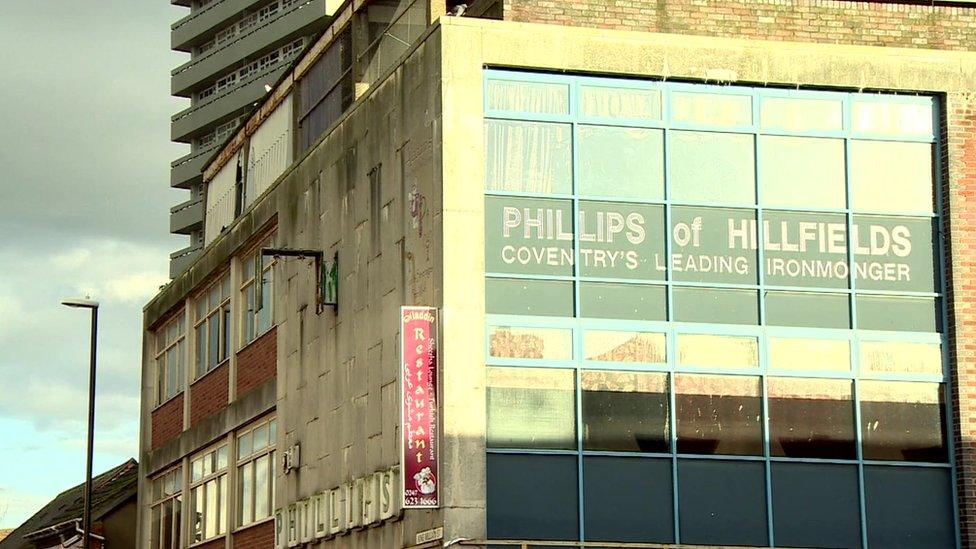

The consequences are felt in areas like Hillfields, one of the city's poorest and most deprived neighbourhoods. Coventry City (the Sky Blues) used to have their ground here, until the team built the Ricoh Arena. Now the area is better known for high levels of crime and unemployment, drug use and prostitution.

Here I meet Susie Murphy, a project worker with the Positive Youth Foundation, which helps troubled teenagers. Nearby a group of boys play football in a scruffy precinct in the shadow of a rundown tower block.

Murphy sees City of Culture status as a way to boost people's self-respect - and give them a reason to stay. "Lots of people are so happy here," she tells me. "They grow up happy here, they know everyone, they enjoy living here, but if people have dreams and aspirations they'll go on from Coventry. To realise those dreams they have to leave, and I think a lot of people don't want to leave."

The bid could also help kickstart physical and economic regeneration in areas like Hillfields. You can see an example of what might be achieved just across the "Sky Blue Way" dual carriageway from Hillfields, in the evocatively-named Far Gosford Street.

This is another survival of old Coventry. Now, with the aid of £10m in grants and backing from the city council, some of the old timber-framed houses are being restored. At the far end, in what used to be a scruffy corner occupied by carpet warehouses, you'll find the FarGo Creative Village, developed by Ian Harrabin and his brother Brian. (Their brother Roger is the BBC's environment analyst.)

A tale of two cathedrals

St Michael's Cathedral was a 14th Century gothic church that became Coventry Cathedral at the end of WW1

After the bombing of WW2 only the tower, spire and outer wall were left - but the spire remains the tallest building in Coventry

Two hundred architects submitted designs for a new cathedral to be built beside the ruins of St Michael's

The winner, Scottish architect Basil Spence, had studied under Edwin Lutyens and favoured a modernist style

Among those rejected was Giles Gilbert Scott, the man who designed the red telephone box

Queen Elizabeth II opened the new cathedral in 1956, and it was consecrated in 1962 with a new War Requiem by composer Benjamin Britten to mark the occasion

At FarGo there's a cafe and a microbrewery, a "beardologist" (or hipster barber), a craft market, and shops selling everything from organic clothing to scooters.

Angela Tebay runs a vintage clothes shop called Aunty Olive's Attic, and like everyone at FarGo is an enthusiast for the City of Culture bid. "There's a lot in Coventry that gets overlooked," she says. "We've got beautiful architecture, even some of the stuff that was created in the 60s that people think is a monstrosity - I absolutely love it. I love the fact that we're a concrete city and I think we should celebrate that."

Comic book artist Al Davison runs Astral Gypsy with his wife Maggie. It's a comic store that doubles as Al's studio. "The problem is there's a lot of stuff going on here in Coventry, there's a lot of art, there's a big film community, a big arts community, but it's a kind of well-kept secret." City of Culture status he says would bring recognition, and perhaps more investment for the arts and culture too.

Coventry has long been a multicultural city. It is early days, but it's clear that cultural diversity will be an important plank of Coventry's bid. Hamish Glen at the Belgrade Theatre says he's already introducing more work by black and minority writers into his programming.

One of the bid's supporters is Pauline Black. She came to Coventry from Essex at the age of 17 to study at Lanchester Polytechnic (now Coventry University, one of two in the city - the other is Warwick). It was the 1970s, the moment when Coventry spawned a new kind of music, 2 Tone, a fusion of Jamaican ska and British punk. The Selecter were a leading 2 Tone band, and Pauline, the child of a Jewish mother and a Nigerian father, became their lead singer.

How 2 Tone earned Coventry a place in rock history

A music style combining ska and punk, 2 Tone was at its height around 1979 and 1980

Most successful bands included The Specials (above, pictured) and The Selecter from Coventry, and The Beat from Birmingham

2 Tone was the name of the record label founded by Jerry Dammers of The Specials, and reflected the black and white clothes worn by the music's fans

Biggest 2 Tone hit was Ghost Town, which reached Number One in 1981 - a song apparently inspired by the state of the band's home town

"I think Coventry has proved itself as a place where even in the hardest of times - and those have been many since World War Two - it has always regenerated itself," she says. "It lives up to the fact that its emblem is a phoenix rising, it has always championed peace and reconciliation across the cultures. Another city couldn't have made 2 Tone, it couldn't have made that synthesis."

For her the bid is a chance once and for all to shake off Coventry's reputation. "So that being sent to Coventry isn't a negative thing, but a positive thing, as it was for me."

More from the Magazine

Paisley in Scotland hopes to kick-start regeneration through culture - it is bidding to become City of Culture 2021. Can the once-wealthy town transform itself?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.