Why Chinese officials are afraid to look too smart

- Published

China's crackdown on corruption has had an unexpected effect. People in influential positions have realised it might not look good if they and their families wear expensive jewellery or flash large amounts of cash at casinos - and as a result some businesses are suffering.

I had already handed her my credit card, but Jane wanted to chat. She was taking her time ringing up the sale.

When we first met, a decade ago, she had just landed her job in one of Beijing's touristy pearl stores, known for selling earrings and necklaces that cost a fortune elsewhere.

For years, every time I visited, the store was crowded and chaotic. Mountains of pearls would be piled high on tables - so many that loose pearls rolled around on the floor. No-one had time to sweep them up, they were too busy making money.

But now, the store was empty. And not just this one. All the pearl stores in this area had fallen silent.

Unsurprisingly, Jane was bored. She was also eight months pregnant. Instead of her usual uniform suit, she wore the stereotypical outfit for expecting Chinese women - a pair of corduroy overalls with a teddy-bear face on the front.

"Where are all of your customers?" I asked. In the hour I had been in the shop, no one else had entered.

"Look outside," she sighed, gesturing to a distant window. "The tourists have disappeared. They are scared of the pollution."

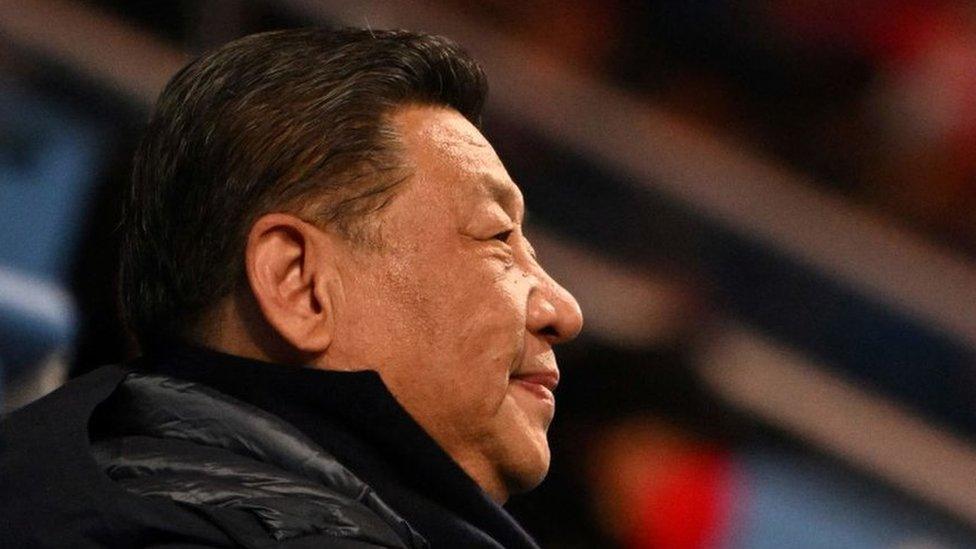

Former state security chief Zhou Yongkang is the most senior government official to be convicted of corruption

"But that is not the worst thing," she continued. "Our Chinese customers used to spend the most, by far. Government people bought our best pearls as gifts. But now, they are all scared of Mr Xi!" she whispered, referencing China's leader, Xi Jinping.

"During the anti-corruption campaign, no one wants to be seen wearing pricey jewellery."

This week, it was announced that about 300,000 officials were punished for corruption in the last year alone. That includes 80,000 who received "severe punishments".

The campaign's work takes place internally, so little is known about who those officials are, what they did wrong, and what happened to them as a result.

But the anti-corruption drive has other, more obvious consequences. Spending on flashy luxury items like watches, has dropped. Jane's pearl store fell victim to this.

Gambling has taken a hit too. The Chinese enclave of Macau, the Las Vegas of the East, has seen profits drop 20% in the past year - all due to the absence of worried officials, it is said.

But that does not mean the Communist Party has cleaned up its act. Far from it.

"I do not think this is making a big dent in how many officials are breaking the law," one China watcher tells me. "That is not what this is about."

People outside China are misunderstanding this campaign, she explains.

Ultimately, Xi Jinping is not trying to groom law-abiding officials. No. He is trying to create legions of obedient officials to implement his policies.

This is a bid to ensure loyalty at every level of the Communist Party - from the upper echelons in Beijing, down to the most remote villages, and stretching right across all of the government's financial empire too.

China's state oil companies, the military and the big banks have all been subjected to corruption inspections. Even the corruption bureau has its own internal inspectors.

For every "rogue official" who might have been trying to carve out a personal empire - by setting up a network of bribes and kickbacks - well, he is taken out and replaced with someone promoted from within, someone loyal to President Xi.

A certain amount of corruption and graft is tolerated, as long as the ultimate priority, party unity, stays intact.

Designer shops in Sanlitun are not as deserted as they sometimes seem

In this environment, all sorts of things are still going on behind closed doors.

High-end lingerie sales are soaring. The logic being that communist cadres will still spend money on private pleasures.

Well-connected friends tell me that "secret" restaurants are viewed as a necessity now. On the ground floor they look like shabby teahouses but banquets are served on the upper floors.

Yes, some luxuries are still popular. It is just the consumption that has gone underground - quite literally, in some cases, I found.

In Beijing, I was always puzzled by a very expensive cluster of stores near my home. It was an outdoor shopping plaza, full of the ritziest European labels - and it always seemed to be empty, with almost no-one going in or out of the shops.

That is, until one day, I entered the underground car park below the plaza. Every space was filled with gleaming cars - BMWs, Lamborghinis, a Rolls Royce or two. And behind the cars stood the individual elevators. Each store has its own plushly-carpeted lift. No need to ever venture outside, into the public eye.

"When do you think the current anti-corruption campaign will end?" I ask a respected expert I know.

He laughs. "It will not end until Xi Jinping feels completely in control," he says. "He is totally reliant on his loyal cadres but everyone else hates him and is just waiting for him to stumble. As soon as that happens, the corruption will come flooding back."

No more need for underground parking lots when that happens.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Thursdays at 11:00 GMT and Saturdays at 11:30 GMT

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule or listen online.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published7 March 2016

- Published3 March 2016

- Published18 January 2015

- Published10 October 2022

- Published25 August 2023