How one man got the world making pesto by hand

- Published

This weekend 100 contestants will be taking part in the world pesto-making championship in the Italian city of Genoa. They will be using just seven ingredients and crushing them all by hand, under the watchful eye of a man who has made pesto his life.

Roberto Panizza is doing something that's as second nature to him as making a cup of tea is to me. Deftly and rhythmically, he rotates his giant 50kg (eight stone) marble mortar, merrily crushing the basil leaves. The huge wooden pestle weighs almost 5kg (11lb).

"It's my only sport at the moment," he says, laughing.

We are at Panizza's restaurant, Il Genovese, where he makes between one and three kilos of pesto like this every day, 1kg at a time. It's Sunday morning - his day off - but he cheerfully demonstrates the correct rotating action before asking me if I'd like to have a go.

"Not too many people have worked in my mortar," he remarks. I tell him I feel honoured.

As he chucks in a couple of cloves of garlic, a handful of pine nuts, a rough sprinkle of coarse salt, and a slug of olive oil, I can't help commenting: "You don't ever measure any of the quantities then?!" But Roberto Panizza is unapologetic about his unscientific method.

"Every time it's different and every time it's good!" he says.

The ingredients he uses are always the same: Genoese basil, local Ligurian extra virgin olive oil, garlic from the village of Vessalico ("good flavour and really digestible"), Italian pine nuts, Pecorino and Parmesan cheeses, and Sicilian salt. The quantities may vary, depending on the balance of flavours he wants - more or less cheesy or garlicky - and on his mood. This, he says, is one of the things that distinguishes pesto made with a pestle and mortar from manufactured pesto made in a blender.

Not that he disapproves of blender pesto. He even has his own line of pesto genovese in a jar, containing exactly the same seven ingredients. He just wants people to understand that they are two different things - and that the best, most authentic pesto is handmade.

"My mum used a blender to make pesto, like all Genoese. Ten or 15 years ago very few Genoese still used a pestle and mortar to make pesto. Maybe one or two elderly people for tradition's sake but it really was something we no longer did," he says.

Panizza had a website on which he sold mortars and in those days orders came from "Brazil, England, Germany, Sicily..." but in Genoa nobody seemed to care about them.

"They were used as plant pots or decorative objects, or even as drinking troughs for chickens because, being heavy, they don't tip over. People really did that!"

In an attempt to change attitudes, he began organising public demonstrations at village fairs.

The seven ingredients

Genoese basil

Ligurian extra virgin olive oil

Garlic (preferably from Vessalico)

Italian pine nuts

Parmesan cheese

Pecorino cheese

Coarse salt

For suggested quantities see the Palatifini Association recipe, external

"When I started, it was revolutionary to make pesto with a mortar. I've seen old people with tears in their eyes watching me make pesto. They would look at me and say, 'You took me back to when I was a little child.'"

In the olden days, for Genoese boys as well as girls, this was the traditional kitchen activity while grandma was cooking, he says.

"The child could play at making pesto because he couldn't hurt himself, there are no knives and no flames. You put him there and he mashes in the mortar and helps you. This really is a very widespread memory - loads of people have told me. This Genoese love of pesto, apart from the fact that it tastes good, is that it takes them back to being children."

His next step, together with a group of like-minded friends, was to set up the Palatifini Association ("palatifini" means "refined palates"). They hit upon the idea of a competition to find the pesto-making world champion. The first was held in 2007, and every two years since 2008 100 people have competed for the title in Genoa's Palazzo Ducale.

Contestants in the 2014 world pesto-making championship

Participants come from all over Italy and abroad. When Panizza's not making and serving pesto at his restaurant, he's busy holding qualifying heats worldwide.

"Half of my time is to produce pesto and the other half is to promote pesto. Pesto is my life!" he says.

When I meet him, he has just come back from a heat hosted by a gastronomy club in Derry, Northern Ireland.

"We go with 10 mortars. We do 50 or 60 of these a year," he says. "I've been to Osaka, Tokyo, Cape Town, Rio de Janeiro, New York, Los Angeles, Toronto, Stuttgart, Paris, Marseille. And to Milan, Reggio Calabria, Rome, Parma. Everywhere."

In addition to the championship, the Palatifini Association has launched a new campaign to protect and promote its world famous local sauce - a bid to have pesto genovese included in the Unesco intangible cultural heritage list. The proposal gained instant backing from the municipal and regional councils, as well as the chamber of commerce. Panizza says it's not about protecting pesto from a commercial perspective but about safeguarding the culture and tradition of the product.

"I was in Dubai in a supermarket and I found a sauce called pesto. It said, 'Made according to Italian tradition and capturing all the flavours of Mediterranean sunshine.' It was made in California and was a sun-dried tomato paste. They called it pesto but it wasn't pesto and that creates a problem for us. Why do they do it? Because the word pesto sells. They use the values of our tradition and twist them to sell their own sauces."

Only one of these jars contains pesto...

Among those backing the Unesco campaign are many of Genoa's basil producers, whose fragrant variety of the herb already has its own PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) - meaning that only basil grown here can be marketed within the EU as Genoese basil ("Basilico Genovese").

In Pra, a coastal area west of the city centre, the hills rising up above the sea are dotted with terraced greenhouses. Proximity to the sea, all-day sun exposure, the mild climate and fresh water streams create ideal cultivation conditions, basil grower Matteo Pezzana tells me. Pra, he says proudly, is renowned for producing the best basil in Liguria - small and tender, light green, oval leaves with a delicate aroma and a pure flavour, and without the minty or lemony notes of many other varieties.

The terraced greenhouses of Pra

An earlier generation of Pra basil growers

Pezzana's wife's family have been growing basil here since 1827, and he shows me every step, from the steamy germination chamber to the fragrant packaging room, where I recognise the basil bouquets from Panizza's restaurant. That's how basil is traditionally sold, Pezzana says, and each bouquet is made by hand.

Pezzana also says there's nothing shameful about making pesto in a blender - his business has been selling fresh pesto in jars since 2003 - and even shares a "Genoese trick" with me.

"Put the blade in the freezer the night before so it's very cold," he says. "You won't overheat the leaf and it won't become black."

But there is one thing he is adamant that people should understand - pesto is a cold sauce.

Pesto is the third most manufactured sauce in the world, after ketchup and mayonnaise, according to the Genoa Chamber of Commerce

"When they ask us how to boil it or, 'How can I warm it?' I go white and say, 'No no, you don't cook it, you just add it on the pasta when the pasta is ready! You can add two spoons of water from the pasta pot to make the pesto more creamy but you absolutely mustn't boil it.'"

And Pezzana agrees that nothing can beat pesto made with a pestle and mortar.

"The mortar is the top because the leaf doesn't get cut, it gets smashed but in a delicate way. It obtains a harmonious sauce."

One hundred competitors are about to prove that at the sixth Pesto World Championship on Saturday. While participants fly in from all over the globe, I nevertheless sense that Roberto Panizza's proudest achievement has been rekindling local passion.

"We convinced them to pick up their mortars again and come and do this competition," he grins, spooning some of the exquisite freshly made pesto into a container for me to take home.

One sign of this, he says, is a 30% increase in production of Carrara marble mortars since the championship started 10 years ago.

"If you go to markets, you can hardly find them any more and, if you do, they are much more expensive because people keep them these days. They used to get rid of them like old pots and pans."

And even though he thinks most people will continue to use a blender because it's faster and easier, he's overjoyed that the value of the family mortar has been recognised.

"It's very satisfying because it's something that will remain. We've reversed the trend. We've saved the mortar by the skin of its teeth."

Update: This year's winner of the Genoa Pesto World Championship is Alessandra Fasce - a 37-year-old assistant cook who lives in Genoa.

The first pesto

"Pesto is a modern sauce that comes from a very old sauce called agliata: a garlic sauce which probably dates back to Roman times. Garlic is the essential ingredient and it's no coincidence that, among the many recipes you can find, the main difference is between pesto with a lot or a little garlic. So it's ironic that nowadays so many pestos are made without garlic because pesto without garlic is a gastronomic oxymoron.

"Many people think that pine nuts are a very typical ingredient of pesto but it is a very modern addition. In the oldest recipes of pesto we have in the 19th Century cookery books, we don't find pine nuts. We have only garlic and oil and cheese. Cheese is very important: both parmesan and pecorino. Like olive oil, basil is also a modern addition."

Massimo Montanari, professor of Mediaeval History and Food History at the University of Bologna

More from the Magazine

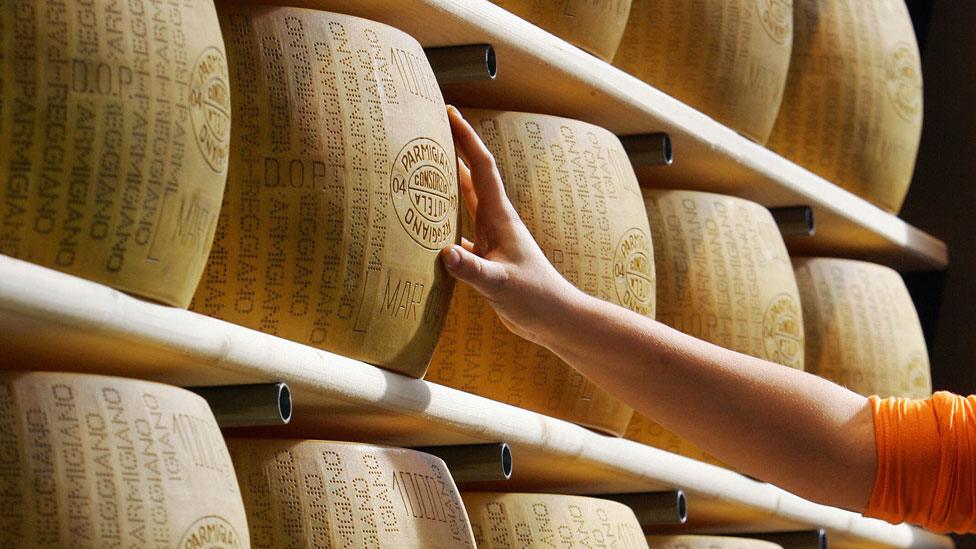

What do Punjab and Italy's Po Valley have in common? More than you might imagine, which explains why immigrant Sikhs from the Indian state became the backbone of Italy's most famous cheese-making industry. They were attracted not by the territory's famous product but rather by the territory itself, explains the mayor of Novellara, Elena Carletti. "They say, 'We live here and we feel like we're still in Punjab because it's flat, there are no mountains, it's hot, it's humid, and the kind of agriculture is more or less the same.'"

The first major wave of Sikh immigrants arrived in the 1980s, when many Italians were turning their backs on what was considered menial, unskilled work. Today Indians (there is a much smaller Hindu community) make up about 60% of the Parmesan-producing workforce,

Read more: The Sikhs who saved Parmesan

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox