Can orcas ever be healthy in captivity?

- Published

Last month SeaWorld announced it was ending its orca breeding programme and said the 29 orcas currently in its parks would be the last. But the company did not step back from its long-held claim that its orcas - also known as killer whales - live long healthy lives. Liz Bonnin was granted unique access to SeaWorld to investigate this claim and weigh the scientific evidence.

Just five months prior to this announcement I was at SeaWorld's Orlando theme park to find out what scientific studies SeaWorld carried out on the welfare of its orcas and to ask for a response to the growing body of independent research on cetaceans - an order of marine mammals that includes dolphins and orcas - which indicates that orcas cannot thrive in captivity.

I asked Dr Chris Dold, SeaWorld's Vice President of Veterinary Services, if he could envisage a time when SeaWorld would no longer keep orcas.

"I don't imagine that future," he replied, "because we know our killer whales are thriving in the habitats where we keep them now."

SeaWorld

The company runs a number of marine mammal parks and animal theme parks in the US

Its three main parks are in San Diego, Orlando and San Antonio

Twenty-three of SeaWorld's 29 orcas live in these three parks, the other six are on loan to the Loro Parque zoo in Tenerife

So why has SeaWorld now made the decision to stop breeding them?

Joel Manby, CEO of SeaWorld, says it's a result of the public's dramatically changing attitudes to orcas since the company started keeping and displaying them in 1964.

"They were feared, hated and even hunted," he says. "Half a century later, orcas are among the most popular marine mammals on the planet. One reason: people came to SeaWorld and learned about orcas up close. Now we need to respond to the attitudinal change that we helped to create."

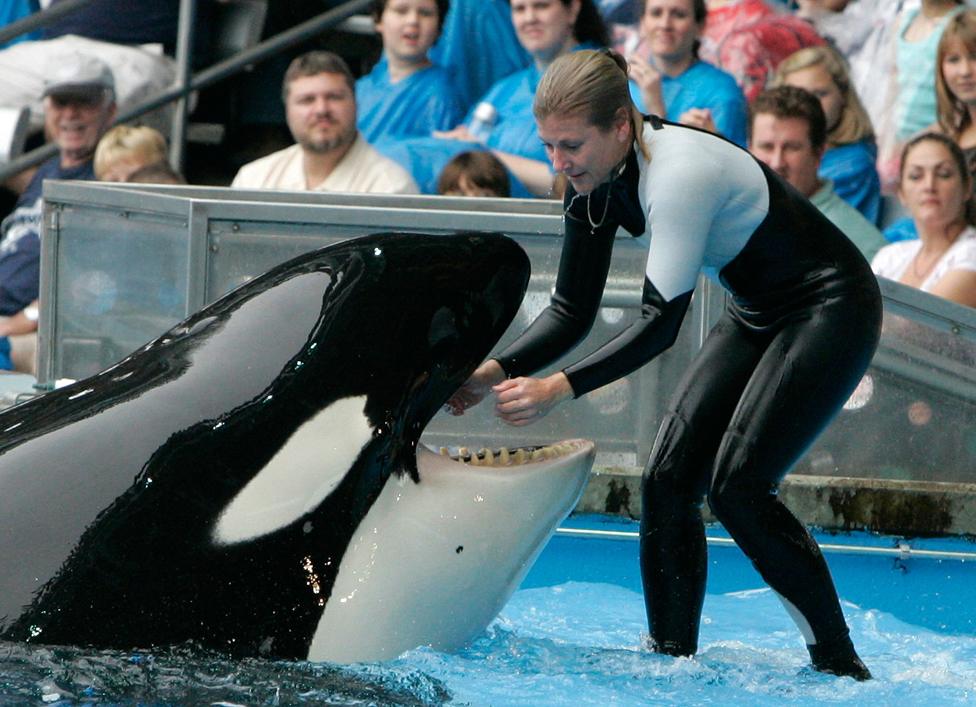

But perhaps an additional reason for the public's shifting opinion about SeaWorld's orcas is the 2013 film Blackfish, which documented events leading up to the tragic death of Dawn Brancheau, a SeaWorld trainer killed by a bull orca named Tilikum.

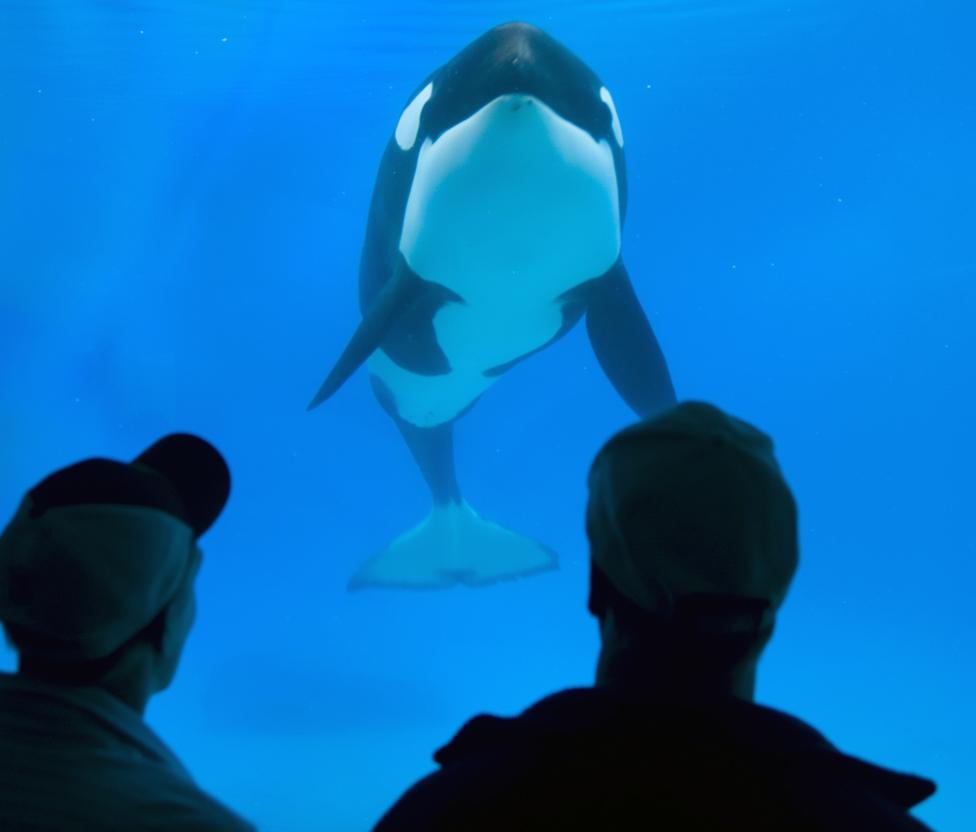

The bull orca, Tilikum, with trainer Jenny Mairot

After the film's release, attendances at SeaWorld fell, as did the company's share price. Like many others, I was moved by the footage and interviews I saw in the film and even went so far as to call, on social media, for SeaWorld to close.

SeaWorld did not take part in Blackfish, so getting the opportunity to hear their side of the story was a welcome development.

I asked Chris Dold why he thought Tilikum attacked and killed Dawn, but he objected to the use of these words. "This was not an attack, this was a terrible accident," he said.

Liz Bonnin speaks to Dr Chris Dold about Tilikum and Dawn Brancheau

So if it wasn't an attack, was it a mistake on Dawn's part? Or was Tilikum behaving somewhat unnaturally?

"Neither of those is true," he said. "There is risk, every day working with animals and those risks are implicit in the size and nature of the animal. Rather than speculate about what happened that day we're focused on putting significant efforts to re-evaluate our approach to safely working with whales."

Tilikum, who was collected from the wild 33 years ago and has lived at SeaWorld in Orlando for 24 of those years, has a tumultuous history. He had already been involved in the deaths of a trainer in a park in Canada and a member of the public in Orlando before pulling Dawn Brancheau into the pool in 2010.

Orca or killer whale?

Sailors once referred to orcas as "whale killers" because they attacked larger whales - over time, however, the words were reversed

In fact, orcas are not whales, they are members of the dolphin family

Nor do they kill humans in the wild

Source: Whales.org, external

But Tilikum is not unique. In fact, two months earlier, another orca had killed his trainer in a park in Spain. According to SeaWorld's records, orcas injured trainers 12 times between 1988 and 2009. These statistics raise an important question: could the constraints of captivity contribute to abnormally aggressive behaviour, or compromise an orca's psychological health?

"There's no evidence whatsoever that there is any mental aberration that is a result of living in a zoological park or otherwise," Chris Dold told me. When asked if he could show me the research that might support such a statement he said there was "experiential evidence" and that "over time deep empirical evidence will come forward".

Dr Naomi Rose, a marine mammal scientist at the Animal Welfare Institute in Washington DC has a different view of the impact of captivity on orcas. She describes orcas as the ants of the mammal world. "I think that orcas are more social than people are. I think their family lives are more important to them than they are for us," she says.

"They cannot be isolated from friends and family because it will in fact cause problems for them. Socially, emotionally, psychologically, physically."

The physical health of SeaWorld's orcas has been brought into question by others too. Images on the internet of orcas' open mouths seem to show broken, worn-down teeth, sometimes with the pulp exposed - a direct route for infection to enter the body.

Worn teeth can be found in some wild orca populations that feed on sharks - over a lifetime, abrasive shark skin will cause the teeth to wear out. Some wild orcas that feed by sucking fish into their mouth can also wear out their teeth eventually, as fish scales repeatedly scrape past their teeth. But SeaWorld's orcas are fed fish directly into their gullets, with their mouths wide open.

According to Naomi Rose, some break their teeth on the enclosures. "They're chewing the walls, they're chewing on the gates neurotically, persistently, on the concrete walls or metal gates through what we call stereotypic behaviour," she says.

Stereotypic behaviour, which includes repetitive swaying, pacing and licking or biting of walls and bars, is an abnormal behaviour carried out by captive animals. It is most common and acute in wide-ranging carnivores, and many scientists believe it is linked to stress.

But Chris Dold says that SeaWorld's orcas wear down their teeth by manipulating their environment. "Killer whales off the coast of the Canary Islands move rocks in order to get to the fish at the bottom. SeaWorld's killer whales manipulate devices that are in the habitat and explore parts of their habitat. If there's a free component the whales will examine and move it around," he says, referring to devices placed in the orcas' tanks for them to investigate.

Find out more

Wild animal biologist and science presenter Liz Bonnin presents Horizon: Should We Close Our Zoos? which airs on BBC2 at 21:00 on Sunday 17 April. Viewers in the UK can catch up afterwards on the iPlayer.

To date SeaWorld has not published any research about its orcas' dental health to confirm the cause of damage to their teeth.

No studies into the orcas' general welfare have been published either. Dold told me: "It's a box that needs checking, for sure, but we have over the years been publishing the baseline information."

Now that SeaWorld has announced the end of its breeding programme, does any of this matter?

SeaWorld currently has 29 orcas, half of which are aged 15 or under, and one of which will soon give birth. How long they can be expected to live is disputed. According to a recent SeaWorld paper its captive-born orcas should live to around 47 years, which is comparable to orcas in the wild. But the method used to reach this figure is controversial and independent scientists are preparing papers to contest the claim. Yet even if a more accurate lifespan for captive orcas is 20 to 30 years, as some scientists argue, SeaWorld will have orcas in its parks for some considerable time yet.

A baby killer whale swimming with its mother in 2004 at SeaWorld in San Diego, California

In August 2014, the company announced a plan to double the size of its orca tanks as part of its "Blue World" project. The new tanks were going to be 15m deep and 107m across. Orcas are known to travel 100 miles (160km) a day, and according to Naomi Rose, these marine mammals need to travel such distances not just to feed but to stay healthy.

Back in October Chris Dold was enthusiastic about these new tanks. "There are a couple of parts of this habitat that are particularly exciting because of what technology is allowing us to do right now," he said. "What we're referring to as the dynamic enrichment programme. It's largely based on the science that's out there in terms of understanding how animals thrive in zoos, a developing field of environmental enrichment."

Unlike the existing flat-walled tanks, which are devoid of any features, the new pools were set to have objects that could be attached to the bottom - puzzles of sorts, for the orcas to interact with - as well as a giant turbine propelling water so that the orcas could swim against the flow. But now that the breeding programme has come to an end, so it seems have plans for Blue World. The signs are that SeaWorld's remaining orcas will live out their lives in the existing tanks.

Naomi Rose wants to see the orcas retired to seaside sanctuaries.

"Sanctuaries are models that are out there for elephants, chimpanzees, big cats and we can do it for orcas," she says.

But SeaWorld makes it very clear on its website that it is opposed to sea pens. "First and most important, our killer whales are thriving right where they are… These are environments that are home for our animals and that allow us to care for them properly," it says "There are other reasons why sea pens are a poor choice for our whales, including exposure to pollution, ocean debris and life-threatening pathogens."

Joel Manby insists the orcas will be well taken care of."For as long as they live, the orcas at SeaWorld will stay in our parks," he says. "They'll continue to receive the highest quality care, based on the latest advances in marine veterinary medicine, science and zoological best practices."

Some in the zoo world see the changes at SeaWorld as indicative of what might happen at other zoos.

The life expectancy of zoo elephants is half that of those working in Burmese timber camps

With a substantial body of scientific evidence about the negative effects of captivity on other wide-ranging carnivores like polar bears and big cats, and with recent research showing that the life expectancy of zoo elephants is half that of those working in Burmese timber camps, David Hancocks, ex-director of Woodland Parks Zoo in Seattle, thinks it's just a matter of time before big changes take place in other zoological institutions.

"As it becomes more and more evident that many of the big animals that are the standard stars of zoos should not be in captivity, I think that the public will react in similar ways to the way they have reacted to the revelations about what was happening in SeaWorld," he says.

He imagines zoos of the future with fewer big charismatic animals, giving attention to small species that do well in captivity, in environments that are stimulating for them, and even with very small life form exhibits that showcase the interdependence and interconnectedness of the natural world. The next question perhaps, is how much and how quickly zoos, and the public, might want to embrace such a change.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.