Is Sunderland about to have an artistic renaissance?

- Published

Sunderland's fortunes have waned since its industrial heyday. Will a UK City of Culture bid revive its glory days?

Sunderland's Wearmouth Bridge is a sturdy arch of green-painted girders opened in 1929 and constructed by the Glasgow iron-founders responsible for the Forth Rail Bridge. It looks robust and utilitarian, if not especially beautiful. Next to it a lighter and rather more elegant twin carries the railway. Far below is the River Wear.

The view from the bridges today is a peaceful one. A short distance to the east you can see the curving breakwaters on either side of the river mouth, stretching out into the North Sea. There are two enormous cranes by the city's docks, but no big ships. A handful of small vessels lie moored to a line of buoys in the river. A solitary fishing boat chugs in from the sea, turns in a great arc in the river and chugs back again. You can hear the cry of gulls above the traffic.

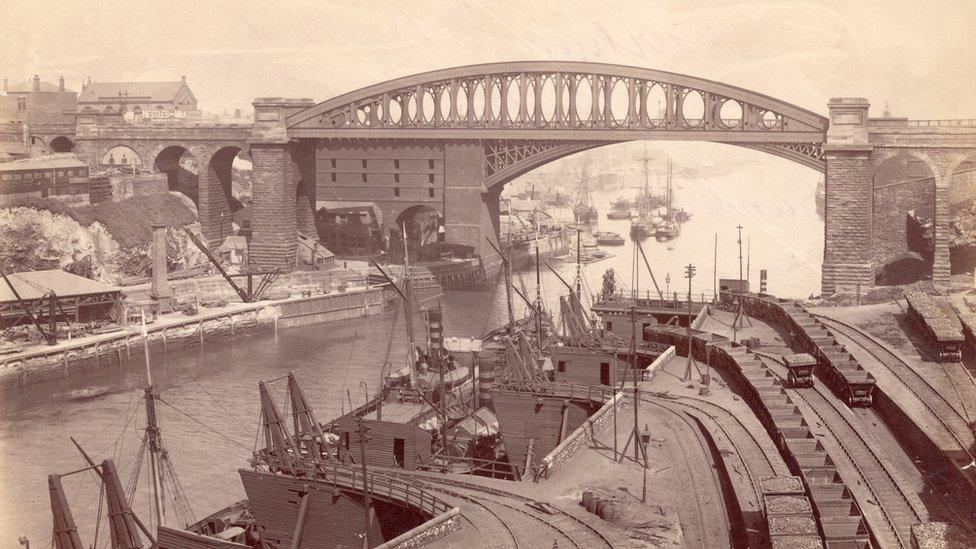

But in 1929 it was very different. Sunderland then was the shipbuilding capital of the world. The banks of the Wear were lined with shipyard.

At the north end of the bridge, where Sunderland FC's gleaming Stadium of Light now stands, was a coal mine, Monkwearmouth Colliery. Close by was one of several glass factories in the town. Sunderland in the 20s was noisy, smoky, dirty... and prosperous.

Sunderland in its Victorian prime

It was a city of makers - a fact reflected in the term Sunderlanders use for their version of the Geordie dialect. Mackem, they call it, as in "We mack 'em, they tack 'em" ("they", according to one explanation, were the shipbuilders of Newcastle, who would take - "tack" - ships built in Sunderland and tow them round to the Tyne to fit them out).

The city's story is a familiar one. The old industries shut down one by one as they became uneconomic - the things Sunderland once made could be manufactured more cheaply elsewhere.

The last shipyard closed in 1988, the Monkwearmouth Colliery in 1993 (the year after Sunderland officially became a city).

The local economy spiralled into decline, with rising unemployment and run-down shopping centres and housing estates.

Manufacturing in Sunderland is by no means dead. The giant Nissan car plant employs 5,000 people and every year builds, as Sunderland people tell you, "more cars than Italy". Just upstream from the Wearmouth Bridge is a vast hangar belonging to the German crane manufacturers Liebherr.

But the emphasis now is on finding ways to regenerate the city and its economy. Which is why Sunderland wants to be the UK City of Culture in 2021.

"We do have a fantastic creative community here," says glassmaker James Maskrey. "Sunderland's always been a great place for making things… It's always been a very creative place and very industrious, and I think we're now moving into a time where that's working in the creative industries as well."

James works at the National Glass Centre on the Sunderland waterfront, on the site of one the city's vanished shipyards. Opened in 1998 and funded by the lottery, the Centre was an early attempt at culturally-led regeneration. It mounts exhibitions of decorative glass and runs courses in glass making.

After going through a rocky patch a few years ago it's now part of the University of Sunderland. James teaches glass-blowing techniques, helps artists express themselves in glass and gives demonstrations to the public.

Glassblower James Maskrey: "Sunderland's always been a great place for making things"

Glass students are attracted by the facilities at the Centre, but also by Sunderland itself. Two of them, Erin Barr and Katherine Lusby, wax unexpectedly lyrical about the place.

"It sounds a bit daft, but one of the things you first notice is the seagulls, because you're next to the sea," says Erin, who comes from Bolton.

"It doesn't feel built-up or dusty or anything like that - it's fresh because of the river," says Katherine. "It's a lovely place to be."

Across the river Paul Callaghan, a successful local businessman, shows me a current regeneration project. At the west end of Sunderland's High Street, more lottery cash is going into a new MAC (music, arts and culture) Quarter.

Paul is a member of the MAC Trust board. The quarter includes Sunderland's Empire Theatre, which plays host to touring West End musicals, as well as two fine Edwardian pubs and the city's old fire station, which closed in the 1990s.

The Sunderland Empire theatre

The fire station is a rather engaging red brick building, more than a century old, with bas-relief sculptures of burning torches, fire buckets and firemen's helmets on the front. It's a reflection of how deeply Sunderland has been in the doldrums that the building has languished empty for over 20 years.

It's now being turned into a restaurant, dance studio and heritage centre, while next door, on what is now a car park, there'll be a 400-seat multi-purpose auditorium

"There's lots happening in the city," Callaghan says. "The council is very ambitious, the university is playing a major role and so are major business people like Nissan… They want the city to succeed and they will invest. We're seeing major investment, a billion pounds or more of investment coming into the city.

"But I believe that any place needs to have a cultural soul - a place where people can develop their cultural talents, can see great art, can participate and shape the place. And that's what we're trying to do here."

Sunderland High Street's former fire station, now an arts centre

One challenge is to involve the wider population. Sunderland's bid director, Rebecca Ball, knows about that. She's spent the last three years running Sunderland's Cultural Spring.

Funded by the Arts Council's Creative People and Places fund, it aims to increase participation in the arts in areas where it has traditionally been low. Ten wards in Sunderland and South Tyneside have been targeted.

"Cultural Spring has been a fantastic opportunity for this area to engage people in a conversation about the kind of cultural life they want in the area," she says, "and I think that's a very good starting point because the City of Culture needs to be owned by the people who live here."

In the Hylton Castle Working Men's Club - a windowless bunker topped by barbed wire on an estate near the Nissan plant - we met one beneficiary of the scheme, Hylton Ukes.

Ukelele playing at the Hylton Castle Working Men's Club

They meet regularly to play pop standards on their ukeleles. They're not young. Harry McCall took up playing the ukulele at the age of 70, seven years ago. David Downing was 78: "Some of my friends suggested I'd be better off learning the harp at my age," he says.

But they are enthusiastic, both about playing - you've not lived till you've heard 20-odd ukes bashing out Urban Spaceman in unison - and also about the City of Culture bid.

Alf Scott, the group's organiser, says: "I think it's a brilliant idea. When you see Hull city, the city of Hull, getting it… why not? Why not give it a go? It can't do any harm, I'm sure it'll bring in a good income, and it'll get the city named. Sunderland used to be a thriving place... well, now it's kind of died a little bit."

As well as these official initiatives there are unofficial ones.

Frankie and the Heartstrings

Frankie and the Heartstrings are Sunderland's most prominent local band. Some of the band's members have branched out and launched Pop Recs, a crowd-funded pop-up record store-cum-artists' hangout.

Drummer Dave Harper describes Sunderland as fiercely proud, fiercely creative, with a DIY ethic. "It does matter that we win," he says, "and we would benefit from it. It would be such a huge step forward to having this city recognised."

"Sunderland is patronised quite a lot of the time, or forgotten about," says guitarist Ross Millard.

"I think with something like City of Culture you go for it, you're in the pot with only a handful of other names, people are talking about you… and now the challenge is, Go on then, what have you got? Let's see what you can do, impress us."

Sunderland in arts and culture

Lewis Carroll was a frequent visitor ot the area and wrote much of his poem Jabberwocky there; his connection with the area was itself explored in Bryan Talbot's 2007 graphic novel Alice In Sunderland

Musicians from the area include Eurythmics musician and producer Dave Stewart, and Britpop band Kenickie, whose singer Lauren Laverne is now a radio DJ and TV presenter

Ross thinks Sunderland people's drive, independence and determination to do things their way may have something to do with the fact that the city lives in the shadow of its bigger neighbour, Newcastle, which has more cultural assets, more performance venues and a greater share of public spending.

That tendency to define itself in terms of opposition to its larger neighbour is widespread.

It even extends to language - the notion that Mackem is different from a generic Geordie dialect is quite a recent one, according to Paul Swinney, who last year published a humorous guide called The Mackem Dictionary (sample entry: "Piat, n. The front surface of a person's head. As in: Yer shudder seen it man, the barl smacked 'im reet in the piat! See also: Fiass").

In his day job, Paul Swinney is an economist for a think tank, the Centre for Cities. He has a warning for his home town and the other cities bidding for the City of Culture title.

"I think it's a great thing in terms of a celebration of civic identity and civic pride and bringing a community together," he says, "particularly in a place that's been hit very hard over the past 30 or 40 years by changes in the global economy and the loss of the shipyards and the coalmines. It's probably made the community much more fragmented, so having this new tool to bring people together is a really positive thing.

"But research suggests these sporting and cultural events don't tend to have that big an impact from an economic point of view. That doesn't mean it's not a good thing to do, but we should be thinking in terms of civic aspect and bringing people together, and not the economic impact."

City of culture contenders profiled in the Magazine

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.