Hillsborough: How does it feel to fight for 27 years?

- Published

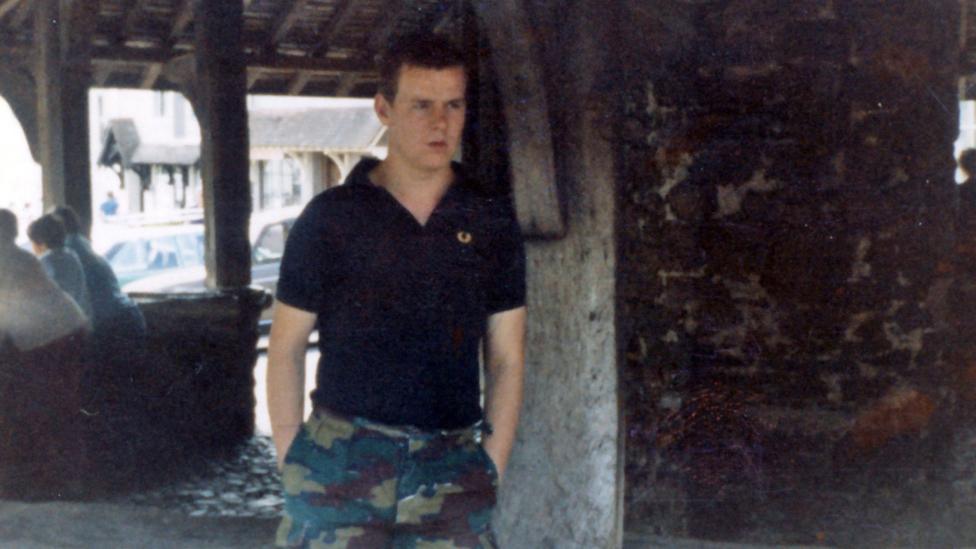

Donna Miller, with a picture of her brother, Paul Carlile, who was 19 when he died at Hillsborough

For years the families of victims of the Hillsborough stadium disaster have been searching for justice, looking to uncover a conspiracy to conceal the truth. Now new inquests have concluded the 96 victims were unlawfully killed.

Tapping phones. Doctoring evidence. Intimidating witnesses.

Not the sort of thing you expect of the authorities in modern-day Britain. But ask the families of those who died at Hillsborough, and they'll tell you that's exactly what has happened.

For years they weren't believed. Even treated as paranoid.

There have been inquiries, investigations and inquests, but for more than a quarter of a century the families have fought to separate truth from myth.

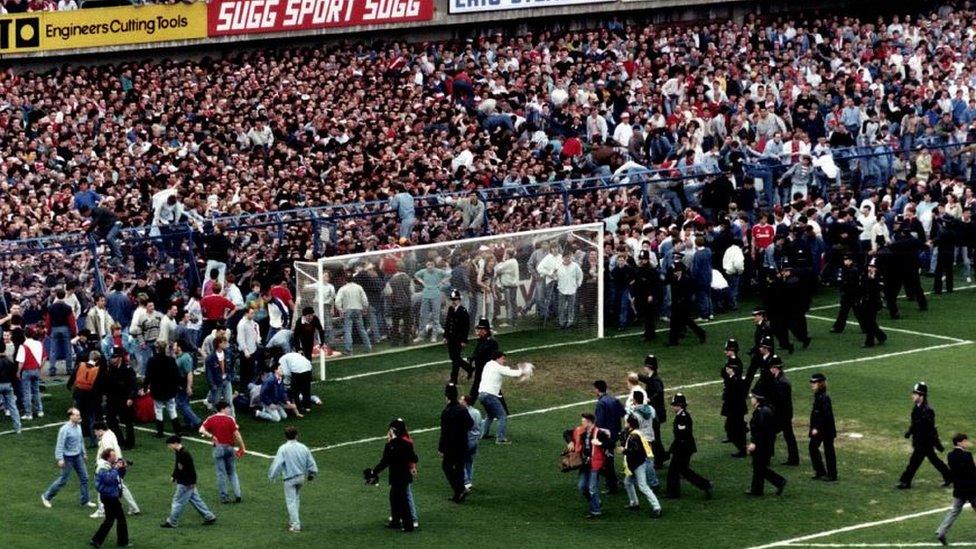

The disaster

Andrew Brookes and Henry Burke never met. One was a car worker from Bromsgrove, the other a roofing contractor from Liverpool. Andrew was 26 and single; Henry was 47, and a father of three.

Both men had a passion for Liverpool Football Club. From the Midlands and from Merseyside, they each followed their team to Sheffield, to watch the Reds play Nottingham Forest in the FA Cup semi-final. And so it was that, on 15 April 1989, they came to be standing yards away from each other inside Pen Three on the Leppings Lane terrace at the Hillsborough ground.

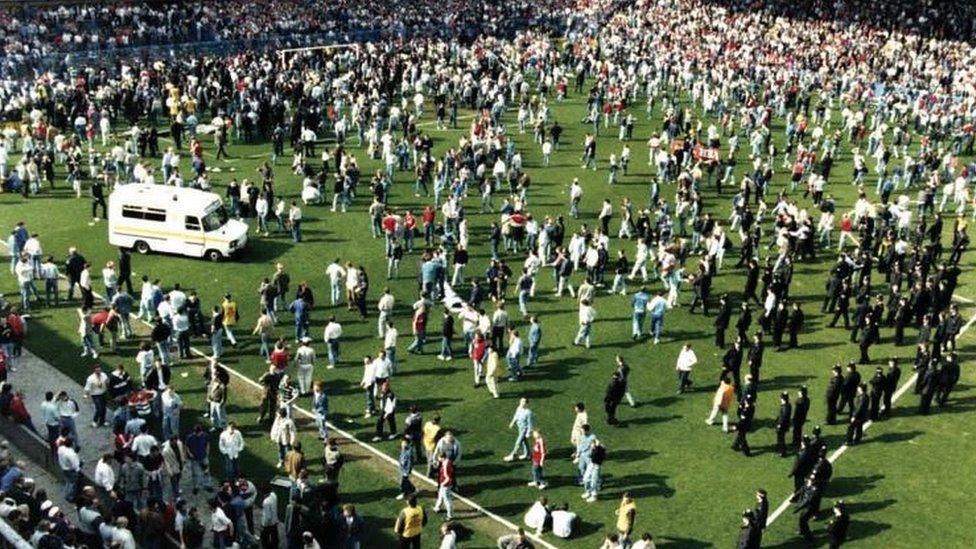

How a crush at a FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest developed, leading to the deaths of 96 football fans.

It was a glorious day. The prize for the winning team - a trip to Wembley for the FA Cup Final.

It was the third consecutive time that the Football Association had chosen Hillsborough to stage a semi-final. The year before, the same two teams had played each other there at the same stage of the competition.

Andrew Brookes and Henry Burke made the journey to Sheffield with 24,000 other Liverpool supporters from all over the country.

The problems began outside the ground, as the numbers waiting to get in built up. The Liverpool fans had access to fewer than half the number of turnstiles that the Forest supporters did.

With the crowd pressure at the Leppings Lane entrance growing, the officer in charge of that area radioed for the wide exit gates to be opened. At 14:52 the match commander, Ch Supt David Duckenfield, gave the order for that to happen. More than 2,000 Liverpool supporters flooded through exit gate "C" in five minutes.

They headed down the central tunnel which led to the standing terraces that were divided into fenced pens. The two pens directly behind the goal were already full. The crush which developed quickly became fatal. Neither Andrew Brookes nor Henry Burke would escape.

When Andrew died, his sister Louise was 17. Henry's daughter Christine was 23. The women would never have met, but for their common bereavement. Now they consider themselves "Hillsborough sisters".

Louise Brookes says that after 27 years the women are "like family but without the genes". She has also become close to Donna Miller, who lost her 19-year-old brother Paul Carlile, a plasterer from Kirkby on Merseyside.

"The bonds we've formed are unique," says Louise. "We do laugh and wonder 'what would our loved ones think?'"

She adds that together they've had to "fight tooth and nail" for their relatives.

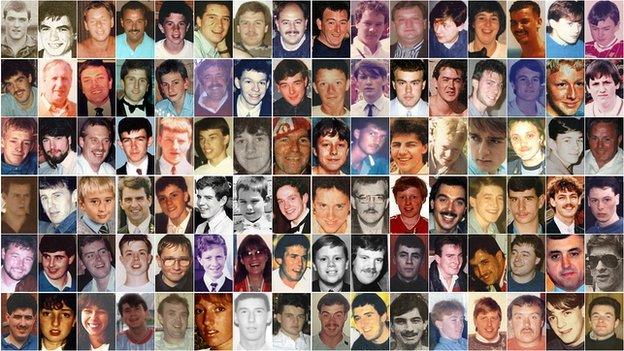

There were 89 men and boys who were killed in the crush at Hillsborough. Seven women, aged between 15 and 38, died alongside them. The 96 were of all ages and backgrounds.

Rose Robinson, whose 17-year-old son Steven died in the crush, has described the Hillsborough families as "a club that you're in but you don't want to belong to".

That club began to form just weeks after the disaster. Travelling to and from Lord Justice Taylor's public inquiry, some families decided that they should organise themselves formally, and thus in May 1989 the Hillsborough Family Support Group was born.

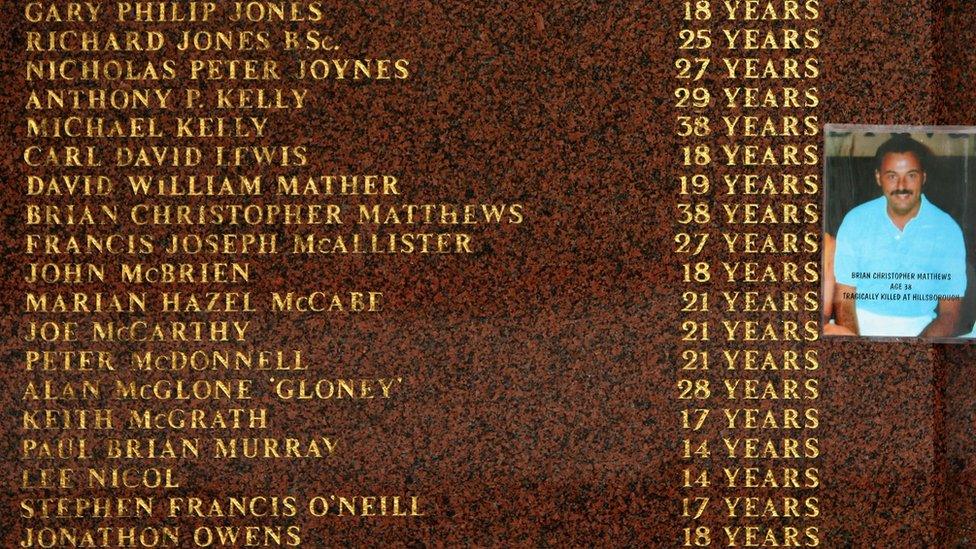

Who were the 96 victims?

Margaret Aspinall, mother of 18-year-old James, was one of the founding members and is the group's current chairwoman.

"I remember saying, 'I don't want to meet any families. They're not going to feel the way I feel. They can't have loved theirs like I loved mine'.

"But I got encouraged to go. And when I went along, I saw the pain, the grief, and the heartache, people still crying… I wasn't the only one. We were going to have a fight on our hands here. Especially after that headline."

Margaret Aspinall, chairwoman of the Hillsborough Family Support Group

Spin, lies and headlines

The families were in the early stages of grief, still coming to terms with their loss. But it became mixed with anger almost immediately, borne out of the suspicion that their loved ones were being set up to take the blame for their own deaths.

The headline Margaret Aspinall refers to was splashed across the top of Britain's biggest-selling newspaper, the Sun. Four days after the disaster, it printed an article under a banner reading "The Truth". It falsely accused Liverpool fans of attacking police and robbing the dead.

Margaret recalls the immediate effect it had. "Somebody showed me the headlines of this newspaper and I thought 'oh my God they're going to blame [those who died] and the fans. We've got to do something about it. We can't allow this to happen."

Jenni Hicks and her then husband Trevor were also founder members of the group. They'd travelled to the match with their two teenage daughters Sarah and Victoria, who both died.

Jenni says: "You have to remember how football fans were looked at in the 70s and 80s. They had a terribly bad reputation then, so really the fans who died at Hillsborough, and the supporters, were prime targets."

That was a concern of Peter Joynes, whose son Nicholas died, aged 27. He remembers the families meeting Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

"I was introduced to Mrs Thatcher, and she said: 'Do you have anything to say?' I said: 'It seems there will be a cover-up.' She said in her drawl: 'Mr Joynes, I can assure you there will be no cover-up', and I'm here years on still thinking there was a cover-up that day."

Barry Devonside was at the match at Hillsborough with his 18-year-old son Christopher. They had chosen to watch the game from different parts of the ground.

Barry was sitting in the North Stand, but Christopher was behind the goal at the Leppings Lane end.

Barry Devonside: "I said: 'I know what the score is, Liverpool are going to take the blame for this. The Liverpool supporters.'"

After the crush, Barry spent all afternoon searching frantically for him. It wasn't until late that night that he was taken to the club gymnasium, which had been set up as a temporary mortuary by the overwhelmed emergency services.

Christopher was brought out in a body bag for his father to identify. Barry remembers that he was then interviewed by two police officers. "They asked me: 'How did you travel here today? Did you stop on the way? Did you have a drink?' I asked: 'What's that got to do with identification?' I didn't believe what they were saying. I said: 'I know what the score is. Liverpool are going to take the blame for this. The Liverpool supporters.'"

It's been argued that the rush to blame the fans began hours earlier, when the match commander David Duckenfield lied to the FA within minutes of the crush. Although it was on his orders that the exit gate had been opened, he said it was the supporters who'd forced their way in.

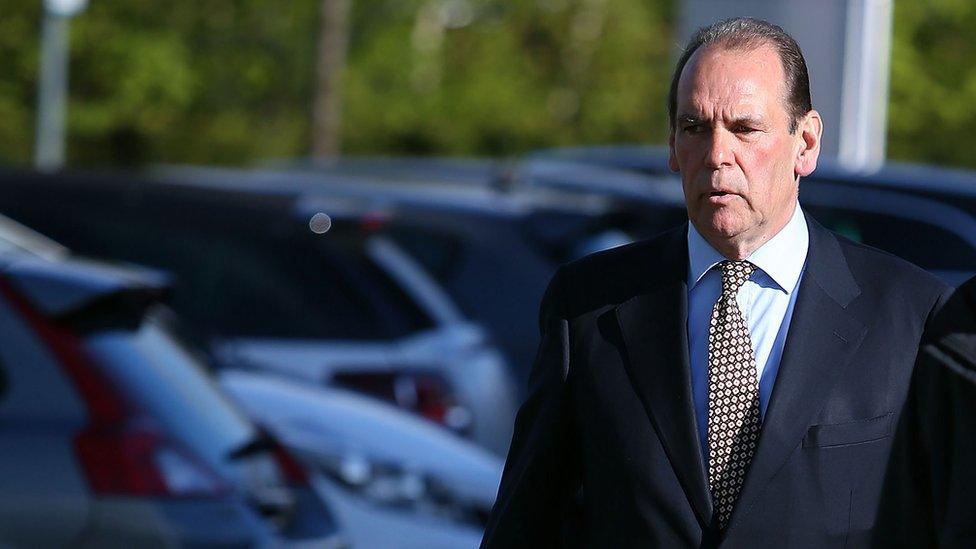

Ch Supt David Duckenfield gave the order for fans to be allowed through the Leppings Lane entrance at Hillsborough

The lie went around the world. It was repeated live on the BBC's Grandstand programme, then on TV news bulletins and it prompted some newspapers to fill their pages with claims of fan misbehaviour.

There were allegations that the fans had been drunk, had arrived late, had got into the ground without tickets. And worse.

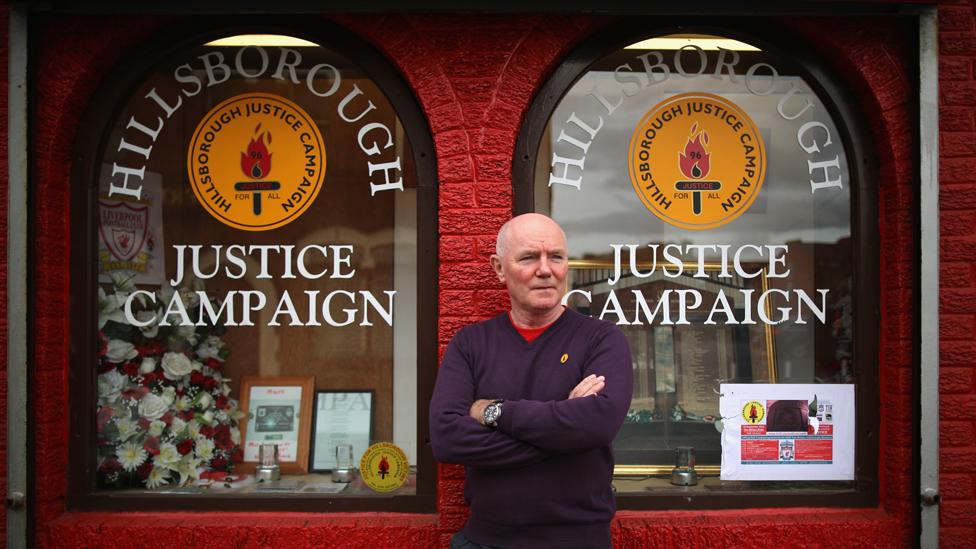

Steve Kelly is a member of the Hillsborough Justice Campaign - another group which supports bereaved families and helps survivors. His brother Michael died in the Leppings Lane end. "My mother read the fact that somebody may have been urinating on my brother. Stealing from his body. Nobody did that. When they saw the Sun newspaper, Mrs Thatcher must have been rubbing her hands, thinking: 'Well, great, this backs us all up. They're just thugs, they're just scum.'"

Steve says he will never buy the Sun again, in line with a continuing boycott of the paper on Merseyside.

Steve Kelly lost his brother Michael in the Hillsborough disaster

For many years the source of the Sun's story was unknown, but in 2012 the Hillsborough Independent Panel found that it was written up from copy filed by Whites News Agency in Sheffield. It was based on conversations agency staff had had with police officers. The agency also spoke to a local MP, Irvine Patnick, and the secretary of the South Yorkshire Police Federation, Paul Middup.

Giving evidence at the second Hillsborough inquests, Paul Middup maintained he had done nothing wrong and that he'd based his comments on what police officers had told him.

The Taylor interim report into the disaster published in August 1989 found "not a single witness" to support "any of these allegations". Lord Justice Taylor also expressed concern that the police had tried to vilify Liverpool fans.

Businessman John Barry, who lived in Sheffield, had witnessed the crush and seen bodies piling up at the Leppings Lane end. By coincidence, he was also studying on the same MBA business course as Norman Bettison, who was then a chief inspector with South Yorkshire Police. He later served as chief constable of both the Merseyside and West Yorkshire forces.

John Barry testified that a senior officer told him that police were trying to "concoct a story that all the Liverpool fans were drunk"

John Barry said that the men went to the pub with their course mates one evening a few weeks after the disaster. He told the inquest he remembers Ch Insp Bettison saying: "I've been asked by my senior officers to pull together the South Yorkshire Police evidence for the inquiry and we're going to try and concoct a story that all the Liverpool fans were drunk and that we were afraid they were going to break down the gates, so we decided to open them."

John Barry said: "I thought, 'why are you saying this to me?'. He knew I had been at the Leppings Lane end and he had seen the bodies piling up and had been totally traumatised by it."

In his evidence to the new inquests, Sir Norman Bettison agreed he had spoken to fellow students in the pub twice during the fortnight after the disaster in a "typical bar-room conversation" but said: "The comments that have been ascribed to me I would not make in a private or public situation."

Sir Norman Bettison denied having the conversation described by John Barry

The families spent more than 20 years claiming a cover-up had involved many police officers, as well as some politicians, and newspapers. But it wasn't until 2012 that their suspicions were given support, with the publication of the Hillsborough Independent Report. And it wasn't until the new inquests in 2015 that a court heard evidence about the subject.

Back in 1990, Lord Justice Taylor's interim report had concluded that hooliganism had played no part in the disaster, and that the main reason for it was "the failure of police control".

But although it exonerated the fans, and provided some comfort to the families, they say that because of the spin and adverse headlines, they have still been plagued by enormous reputational damage for 27 years.

Charlotte Hennessy has grown up knowing nothing but Hillsborough. She was just six when her dad Jimmy died at the match. Now 33, and a parent herself, she has childhood memories of being bullied as a result of the disaster.

The family had moved away from Merseyside to North Wales. But there, she was taunted. "Children would say things. I'd say: 'Why are they saying mean things what's wrong with Liverpool fans?' I didn't understand until I was a teenager and I got the internet and started doing a bit of research. I've had to grow up with that all my life. Since I was six I've had to fight against that."

Jimmy Hennessy died at Hillsborough - his daughter Charlotte has grown up "knowing nothing but Hillsborough"

Hillsborough was a disaster which happened in the pre-digital era. It was typed up on paper, written down in notebooks, on memos, in minutes of meetings.

Since 2012 when the Hillsborough Independent Panel disclosed documents running to 335,000 pages, searching for information has been possible via a few mouse-clicks, external.

But for years the families were denied access to much of this, and they suspected that evidence was being hidden and suppressed. They went in pursuit.

Amended statements

In the mid-1990s, through criminologist Prof Phil Scraton, they discovered that some of the statements written by police officers after the disaster had been edited and amended. But it was many years before they found out just how widespread it had been.

South Yorkshire Police (SYP) officers who'd been on duty at Hillsborough were asked to write down their recollections. Unusually, however, they were told to record them on plain paper - not in their official pocket notebooks, with traceable numbered pages.

Originally the statements were intended for internal use only, to help South Yorkshire Police's legal team as they prepared for the Taylor public inquiry. But when West Midlands Police was appointed to investigate the disaster, its team asked for the statements. That was when senior officers, and the SYP lawyers decided they should be put through a vetting process before being disclosed.

The statements went to the SYP solicitors for checking, and were then sent back with suggested changes, to be typed up again before being submitted to the Taylor Inquiry.

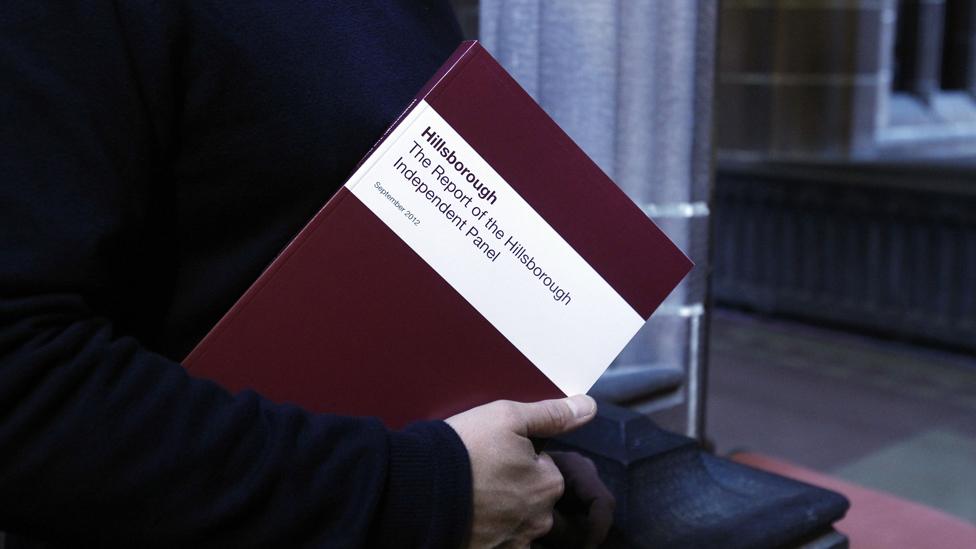

The Hillsborough Independent Panel at a 2012 press conference

Once the families learned that police statements had been altered, they began to believe that there had been a co-ordinated attempt to manipulate evidence.

They pushed for it to be investigated. In 1997 the new Labour Home Secretary Jack Straw set up a Judicial Scrutiny of Evidence.

The Scrutiny was conducted by Lord Justice Stuart-Smith, who didn't get off to a good start, offending the families on the first morning. Asking if everyone had arrived, he said: "It's not like Liverpool fans to turn up at the last minute!" He later apologised for "an off-the-cuff remark" which he said he "deeply regretted".

Not for the first time, the families felt that an establishment figure was likely to be against them.

The Scrutiny found that most of the amendments made to police statements were "of no consequence" and it rejected the allegations "of irregularity and malpractice". The home secretary announced that there was no new evidence which could challenge previous verdicts and rulings.

The families had the backing of local politicians. But beyond Merseyside it was harder for the families to win public support. Trevor Hicks says: "We always tried to play fair, play the Establishment rules. But the Establishment wasn't listening." Frustration reached boiling point in 2009 when a lone cry of "Justice!" was directed at a politician, Andy Burnham.

Andy Burnham (then culture minister) speaking at Anfield in 2009

The then-secretary of state for culture, media and sport was speaking at Anfield, at the Hillsborough 20th anniversary memorial service. "Justice for the 96!" rang out across the Kop, thousands of survivors, campaigners, and members of the general Liverpool public chanting so passionately that at last Westminster ears pricked up.

It was the moment that everything changed. Andy Burnham is a Liverpool lad himself. That he's an Evertonian doesn't matter - Hillsborough is the one subject which unites the red and blue halves of the city. Burnham took the message to government and full early disclosure of all public documentation about the disaster was promised.

In 2012 the result of that pledge was the publication of the Hillsborough Independent Panel Report. It confirmed the families' suspicions about the amended statements and many other issues.

The system by which statements were altered was fully exposed.

The Hillsborough independent panel report was published in 2012

The panel revealed that "hundreds of officers' statements were vetted" and that 164 statements were substantially changed. References to "chaos", "fear", "panic" and "confusion" were deleted, as were criticisms of inadequate police leadership. Comments about fans arriving late and drunk were left in.

Phil Scraton, who sat on the panel, said later: "There was a mindset amongst the police investigators which hinged on hooliganism, drunkenness, late arrival and ticketlessness." The entire evidence base of the investigations had to be questioned.

In the wake of the panel's report, the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) launched a criminal investigation into the aftermath of Hillsborough. The IPCC says it is now investigating the amended statements of more than 250 officers.

One account which was edited was that of William Crawford who was serving as a police sergeant in 1989.

Floral tributes laid near the Leppings Lane entrance to Hillsborough

On the day of the disaster he'd been in charge of a group of officers near to the tunnel leading to the Leppings Lane terraces. In his original statement he commented that at previous matches he'd worked at, more officers had been allocated to police the same area. In the amended version of Sgt Crawford's statement that paragraph was removed.

He says: "It was my observations, my opinion, and I thought it was important." Now retired, William Crawford says he was only told that his statement had been tampered with in 2014, when he spoke to IPCC investigators. "I wasn't happy. I thought it was important, and it was removed because it was criticism."

Former PC Fiona Nicol had a slightly different experience.

Also now retired, in 1989 she was stationed by the Leppings Lane terraces when the crush developed. She tried to rescue fans including 14-year-old Adam Spearritt, who did not survive.

In the week after the disaster, she was summoned to police headquarters and told to write up her experiences. She was young and new in service, and felt under enormous pressure. She was put in a small room and says that a senior officer kept coming in and taking her papers away.

The former PC says that at one point the officer queried her description of the crowd in the central pens before kick-off.

"I'd written 'full' and he didn't like that particular word, 'full'. He said, 'don't use that wording'."

She agreed to remove it and says now: "I'm angry at myself for doing it, and I'm angry at myself for letting someone make me do it."

The new inquests heard evidence about the practice of changing statements. Senior officers said they'd been following legal advice, and had only removed opinion and extra comment from the accounts.

Fiona Nicol also spoke publicly about her experience for the first time when she gave evidence. She says that she kept quiet for years while she was still a serving South Yorkshire Police officer. Of her colleagues, she explains: "They were trying to take the blame from themselves, the senior officers, and they didn't care who got the blame instead… and it was lower ranking officers like myself and others that they were throwing some blame at. And at the fans themselves."

This made her feel "extremely angry. And frightened, extremely frightened. I was frightened for a lot of years".

South Yorkshire Police is not the only force to be accused of malpractice. In the wake of the disaster West Midlands Police (WMP) took on three roles. The force was responsible for producing evidence for the Taylor Inquiry, as well as for a criminal investigation, and for the coroner.

The intimidated witness

WMP was tasked with conducting an independent investigation. But survivors now speak of being treated as "the accused". Many relatives believe that the West Midlands officers were in league with their South Yorkshire colleagues in trying to deflect the blame away from the police.

Nick Braley, who was 19 and at university in Sheffield, went to the match. He speaks of the police looking "lost and dazed" outside the ground. He says he remembers a mounted officer inflaming the situation there. He went through Gate C and down the tunnel into pen three, where he was caught in the crush. He says that his relief at getting out has been mixed with guilt at surviving.

After the disaster the student was interviewed by a WMP officer. He is one of several survivors who've spoken out about having similar experiences. Nick describes the meeting as having been "confrontational".

West Midlands Police were criticised by survivors' families for their investigation into their South Yorkshire colleagues

It started civilly. But he says he was quickly accused of having bought a touted ticket, which he denied. Nick says he was then asked about what he'd had to drink.

"When it all went horribly wrong was when I mentioned that a mounted policeman had effectively charged into fans outside the ground and had made a bad situation worse. At this point the DCI flipped. Some of his questioning became really aggressive. He asked: 'Who are you to make accusations against the police? You can't get away with it. Who do you think you are?'

"I started getting asked about my political persuasions. 'Are you a member of the Socialist Workers party? The Workers' Revolutionary Party? Are you a student agitator?' He observed that I'd been wearing my Free Mandela T-shirt. He said: 'You're a student out to get the police.'"

The officer was trying to influence the statement, Nick says. "Having now seen what was written down, I believe he was looking to collect evidence that fitted the police narrative of drunken ticketless fans. He threatened me. He said: 'Do you know what wasting police time is?' He said he'd check my criminal record and make a case for me wasting police time.

"I felt scared and intimidated. This guy's got all the power. I was just a student. I stood my ground as best as I could but it was not a nice position to be in at all."

The IPCC is now investigating the conduct of West Midlands Police, and is looking at police officers' attitudes and lines of questioning when speaking to witnesses. The IPCC is also examining how WMP gathered evidence for the Taylor Inquiry, and the original inquests.

Evidence missed - the first inquests

For more than two decades after the disaster, one of the biggest running sores for the families was the first inquests. They were angry at the way the hearings were conducted, feeling that vital evidence had been excluded, and they were devastated by the verdicts of accidental death.

The first coroner, Dr Stefan Popper, decided not to call witnesses to speak about events after 15:15 on the day of the disaster. It meant that no evidence was heard about rescue and evacuation. And it was based on the premise that all of those who died were fatally injured or dead by 15:15.

Police and fans carry away an injured fan from the scene at Hillsborough

From very early on, some families suspected that their loved ones had still been alive and saveable after this time. Anne Williams was one of the first bereaved relatives to explore this.

Anne's 15-year-old son Kevin died at Hillsborough. She had been shown a photograph of an off-duty policeman trying to resuscitate him. She was told that the policeman had felt a pulse on Kevin at 15:37. Then she learned that a special constable, Debra Martin, had been with the teenager in the gymnasium which was being used as a temporary mortuary. She had made a statement in which she described Kevin opening his eyes and saying "mum" before dying at 16:00.

To Anne, the first inquests were worthless. Along with other families she refused to accept the death certificates issued after those hearings. She felt strongly that her son's death had not been fully investigated, and she dedicated her life to fighting for fresh inquests. Anne died of cancer in 2013. She did not live to see the new inquests begin in March 2014.

Before she died, Anne spoke to me about her long battle for justice. "I knew I was right in 1991… We knew that they shouldn't have imposed the 3.15 [cut-off]."

Because Anne suspected that the first inquests hadn't heard all the evidence, she set about the task of finding witnesses herself. She began with the off-duty police officer and the special constable.

Anne was aghast to discover that they'd both agreed to change their statements after meeting with West Midlands Police officers. Anne asked them if they would stand by their original accounts. They both agreed, and they each confirmed that they had seen signs of life in Kevin after 15:15.

She then traced the survivors who had carried Kevin across the pitch on an advertising hoarding, and with the help of TV journalist Roger Cook she found the ambulanceman whose vehicle had driven past Kevin as he was being resuscitated (enabling them to time this precisely).

Anne fought for a new inquest. She made her case to the attorney general's office three times. Three times she was turned down, and told that "it was not in the interests of justice". Eventually she applied to the European Court of Human Rights. Just before the 20th anniversary of the disaster she learned that she had been unsuccessful there too.

But when the Hillsborough Independent Panel's report was published in 2012, it paved the way for new inquests for all 96 Hillsborough victims. Anne submitted her papers to the attorney general for the fourth time.

By now in a wheelchair, she was brought to the High Court to watch the historic moment when the verdicts of accidental death were quashed.

December 2012: Anne Williams at the Hillsborough inquest

Afterwards she told me: "It's a good feeling, because they bounced me from one wall to the other, and I knew what they were doing. I thought, 'They're wearing me down, but I'll wear them down before they wear me down.' And I've actually done it."

Since Anne's death her family have carried on the fight for justice.

Anne's daughter Sara was only nine when her big brother Kevin died, and so she grew up watching her mum campaigning. "I never doubted she was right, I just didn't ever think we would get this far."

In December 2013 Anne Williams was honoured at the BBC Sports Personality of the Year ceremony. She was posthumously given the Helen Rollason award for outstanding achievement in the face of adversity.

Anne Williams was posthumously honoured at the 2013 BBC Sports Personality of the Year Awards

Another bereaved mother, Terri Sefton, also challenged the way the first inquests had been conducted. Terri's son Andrew died in the crush. He was 23.

Buried in the pages of the Hillsborough Independent Panel Report there's a fascinating document. It's a note made by the first coroner, Stefan Popper, after taking a call from Terri in 1993. She had apparently phoned to ask the coroner whether he thought the inquests should have been different.

He wrote, external: "She had never felt that she had got the facts or had her questions answered. I explained that I had retired and that I did not think that I should make any comment and that as far as I was concerned the proceedings were over. She said that might be so for me but not for her… she had previously told me she had not been satisfied with the conduct of the inquest.

"She felt that she, an ordinary mother, had been caught up in a huge intrigue and that none of the questions that she had wanted answered had been answered. I said to Mrs Sefton that whilst she had the right to speak her mind, I had the right not to listen. That I had now retired as coroner and that there was nothing more that I wished to discuss on this."

The 15:15 cut-off wasn't the only one of the first coroner's decisions to prove controversial. Another was his request for blood alcohol levels to be taken from every one of the victims - including the children.

Criminal record checks about some of the deceased were also made on the police national computer. It's not suggested that the coroner knew this, or that the results of the checks were used in the inquiries or inquests. The Hillsborough Independent Panel said that in its view "criminal record checks were carried out on those of the deceased with recorded blood alcohol levels in an attempt to impugn personal reputations".

Stefan Popper was the coroner at the first Hillsborough inquest

At the 1990 inquests, the families had hoped for a verdict of unlawful killing to be recorded. But instead the jury decided that the deaths had been accidental. The verdicts caused outrage, prompting an emotional outcry by some families. Trevor Hicks said after the hearing: "It is a lawful verdict, but in our opinion it is immoral." In 2016, the jury at the second inquests was not given the option of delivering accidental death verdicts.

Speaking to the BBC in 2009, Stefan Popper said he felt he'd been unfairly criticised for the way he conducted the original inquests. "I feel I was fair, I made a full inquiry. I had no intentions of hiding evidence from anybody… but I had to do it within the parameters of the coronial system. I may make wrong decisions but I do feel aggrieved that I'm treated as somebody who misbehaved and tried to subvert the evidence, which I have not."

What the coroner could never do was to find someone criminally liable for the disaster. That falls outside the power of an inquest.

Who was to blame?

Many families have struggled with the fact that, 27 years after Hillsborough, no organisation or individual has been convicted of any charge related to it.

In August 1990 the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) announced that there was "no evidence to justify any criminal proceedings" against South Yorkshire Police, Sheffield City Council, Sheffield Wednesday FC, or the club's engineers Eastwood & Partners. The DPP also found that there wasn't enough evidence to charge any individual person with a crime connected to Hillsborough.

South Yorkshire Police did pay out compensation money to some of the injured and bereaved. Sheffield Wednesday FC, Eastwood & Partners and Sheffield City Council also made payments. The Hillsborough Independent Panel Report calculates that a total of £19.8m was paid.

In addition, according to the same report, SYP paid compensation of £1.5m to 16 of its own officers.

But in settling the claims, the force did not admit liability.

Disciplinary proceedings for "neglect of duty" began against the match commander Ch Supt David Duckenfield, and his deputy Supt Bernard Murray. But they were discontinued after Ch Supt Duckenfield retired early on medical grounds. The Police Complaints Authority decided that it would be unfair to proceed against Supt Murray on his own.

1998: Bernard Murray (left) and David Duckenfield arrive at Leeds Magistrates Court

The Hillsborough Family Support Group decided to bring a private prosecution against the police officers.

In 2000 the families got their moment in court. David Duckenfield and Bernard Murray were charged with manslaughter and misconduct in a public office.

But the jury acquitted Bernard Murray and was then discharged, having failed to reach verdicts on David Duckenfield.

Another legal door had closed. The families would have to wait another 12 years before the launch of two fresh criminal investigations, formed in the wake of the Hillsborough Independent Report.

Operation Resolve, run by Assistant Commissioner Jon Stoddart, is currently investigating the 96 deaths from a criminal perspective.

Running in parallel to Operation Resolve is the biggest criminal investigation into alleged police misconduct in England and Wales ever undertaken. The IPCC is looking at whether any crimes were committed in the aftermath of the disaster, which includes whether there was an organised cover-up.

Both investigations are being run from the same office building in Warrington - an uninspiring grey block on an anonymous business park. Inside are hundreds of staff, including former police officers. They have analysed hours of video footage, and many thousands of photographs, documents and other material. Operation Resolve has also been tasked with providing information and evidence for the new inquests.

Birchwood Park, Warrington, where the recent inquest has been taking place

Was there surveillance?

One of the areas that the IPCC is investigating is whether Hillsborough families were put under surveillance. Several have suspected for years that their phones were tapped or that they were watched.

The IPCC says it has now interviewed 22 people who've made allegations about surveillance, and that it's "pursuing further lines of enquiry in relation to three specific complaints". Investigators have also approached BT for help with information about the phone network at the relevant time.

Jenni Hicks, who lived in Middlesex at the time, remembers picking up the phone in 1990 to speak to a friend in Liverpool. But their conversation became crossed with another call, being made by Hilda Hammond, whose son Phillip died at Leppings Lane. Both women, whose husbands were active members of the Hillsborough Family Support Group, are convinced that the interference was the result of phone tapping.

Jenni Hicks was one of several Hillsborough campaigners who alleged their phones had been tapped by police

Julie Fallon had a different experience. Her brother Andrew was in the crush. Her mother, Terri Sefton, was the woman who called the first coroner to complain about the original inquests. Julie is now the sole surviving member of the family.

She remembers her mum dropping her off at home one day shortly after those original inquests. Julie says: "My mum started to walk across the road towards a shiny black car with two gentlemen sitting in it. One had his hands on the wheel and the other had, in all the great traditions, a newspaper out.

"She was tapping on the window, and she said to them: 'Look, lads I'm just popping into my daughter's and having a cup of tea, and then I'll go home. So you might as well get off.' And the guy folded up his newspaper and said 'Thank you, Mrs Sefton' and drove off.

"I said to my mum, 'Who was that?' And she said: 'Oh it's the police… they've been following me for about a week.'

"We used to joke about it in the family but we never reported it, because who would you report it to? You'd report it to the police, and it was them who'd been sat outside."

For years the family's claims of amended statements, tapped phones and suppressed evidence fell on the deaf ears of a largely sceptical country. It wasn't until the Hillsborough Independent Panel was formed in 2010 that things changed.

Truth Day

The chairman of the Panel was the then Bishop of Liverpool James Jones. He says now that "the families often said to us during the process that 'this is the first time that anybody has ever listened to us; that anybody has ever taken us seriously'".

The Right Rev James Jones was the chairman of the Hillsborough Independent Panel

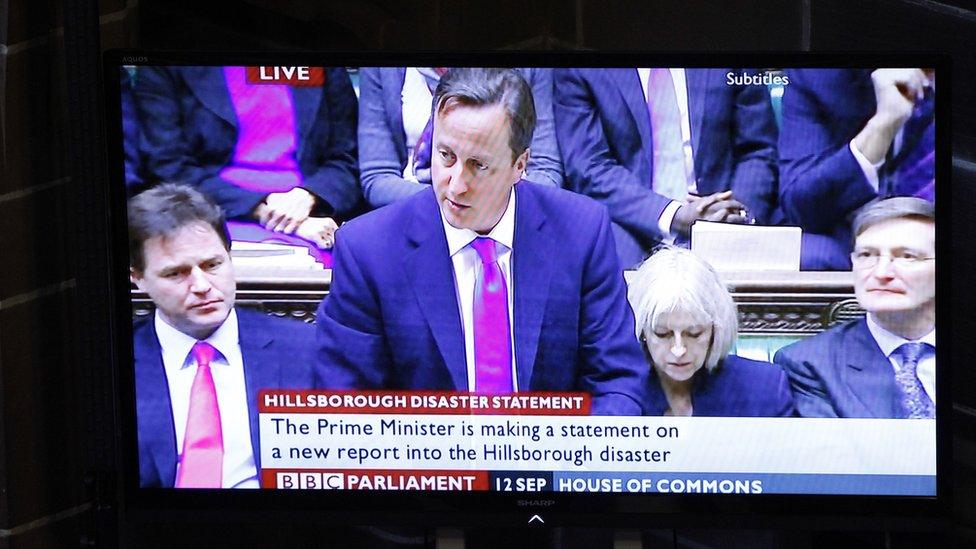

Some families refer to the date of the publication of the Panel's report - 12 September 2012 - as Truth Day. The prime minister got to his feet in the House of Commons and apologised. It was the ultimate establishment acknowledgement of the validity of the campaigners' fight.

David Cameron said: "These families have suffered a double injustice.

"The injustice of the appalling events - the failure of the state to protect their loved ones and the indefensible wait to get to the truth.

"And the injustice of the denigration of the deceased - that they were somehow at fault for their own deaths.

"On behalf of the government - and indeed our country - I am profoundly sorry for this double injustice that has been left uncorrected for so long."

The apology was well received by both families' and survivors.

The second inquests - what has been learned

The second inquests have provoked mixed feelings for both families and survivors. Some have spent so much time tracing their own witnesses and finding their own evidence that they feel they've learned little new information about their loved ones' deaths. Julie Fallon feels that she fits into that category - although the inquests have still been enormously important to her.

"The whole process, for me, has been about other people's awareness. There is barely anything that we didn't know. It's about clearing people's names, it's about getting those facts out there."

Other families say they have learned information about their individual cases which they didn't know before.

Barry Devonside went to court every day of the first inquests and has attended throughout the two years of the second set. This time around, he's learned much more about the circumstances of his son Christopher's death.

Most notably he's been told, for the first time, that the teenager could have been rescued. "Our only son was laid down on his back in the penalty area and… we were told that he could have been alive - could have been alive - for at least an hour. We have no evidence that anybody tried to save his life. And all we've got now is memories of a lovely, lovely lad and an excellent son."

Many families have also seen their loved ones on video footage of the disaster for the first time. Since 2013, work has been done to try and identify every one of the 96 victims on the television pictures of the day. Because BBC cameras were at Hillsborough to film the FA Cup semi-final match for the Grandstand programme, there is hours of footage.

Margaret Aspinall was shown video of her son James lying on the pitch with a coat over his head. A former police officer told the inquests that he'd put his tunic over the 18-year-old "out of respect" as he thought he was dead.

The footage of him lying alone, with people stepping over him, came as a shock.

"It's my nightmare. I go to bed of a night and I ask James for his forgiveness because I wasn't there to have done something for him. I keep saying 'I'm so sorry, son, I'm so sorry'…

"To put a coat over his face, what chance did he have then, because other people must have thought he'd died? I have to live the rest of my life knowing that."

The inquests have enabled some topics to be aired before a court for the first time, including the amended statements, and the emergency response after 15:15. And they were also the platform for the first ever apology from the match commander David Duckenfield.

The families last faced him across a courtroom at the private prosecution in 2000. Fifteen years later, they crowded into the coroner's court to see him again.

The former chief superintendent accepted that as the crush developed, he "froze" in the police control box. He accepted that his failure to order the closure of the tunnel was the "direct cause of the deaths of the 96 persons".

And of the lie he told to the FA, he admitted: "I said something rather hurriedly, without considering the position, without thinking of the consequences and the trauma, the heartache and distress that the inference would have caused to those people who were already in a deep state of shock, who were distressed. I apologise unreservedly to the families."

Some relatives left their seats and walked out of the courtroom in tears.

Hillsborough timeline

15 April 1989: Ninety-four football fans die and hundreds more are injured after overcrowding at a stand at Sheffield Wednesday's Hillsborough ground, at an FA Cup semi-final fixture between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest

19 April 1989: The Sun publishes a front-page story entitled "The Truth", accusing drunk Liverpool fans of having caused the disaster; a 14-year-old boy dies from his injuries, bringing the death toll to 95

August 1989: A report by Lord Justice Taylor criticises police at the stadium for "failing to take effective control"

1991: An inquest returns a verdict of accidental death

1993: Tony Bland becomes the 96th victim after his life support is turned off - he had been in a persistent vegetative state since 1989

1998: The Hillsborough Family Support Group brings a private prosecution for manslaughter against David Duckenfield and Bernard Murray, the two policemen in charge on the day

2000: A jury finds Murray not guilty, and fails to reach a verdict on Duckenfield

2009: On the 20th anniversary of the tragedy, the Hillsborough Independent Panel is set up; it is subsequently given access to all government papers relating to the event

September 2012: The panel's report finds evidence of an orchestrated police cover-up, and says that up to 41 of the dead could have been saved with improved medical care

December 2012: The original coroner's report is quashed by the High Court

March 2014: The new Hillsborough inquest begins in Warrington

January 2016: The coroner Sir John Goldring begins his summing up after 267 days of evidence;

April 2016: The inquest jury concludes that all 96 fans were unlawfully killed

Later, Charlotte Hennessy said: "I feel that he's only said it because he's been forced to, because he's been made to attend the new inquests. And I can categorically say now, I do not accept your apology, David Duckenfield. I do not accept it. You made us live a lie for 26 years. That is beyond cruel. And I'll never forgive it, and I'll never forget it."

Twenty-seven years of campaigning have taken their toll on the Hillsborough families and survivors. Some, like Anne Williams, did not live to see the justice that they craved. For many of those who've spent the last two years listening to harrowing evidence at the inquests, the pain continues.

One relative who attended nearly every day of the hearings suffered a heart attack as they drew to a close. His family believes that the stress of the court process was partly to blame.

And with the possibility of prosecutions still to follow, there could be many more difficult months ahead.

The former Bishop of Liverpool James Jones now acts as the home secretary's adviser on Hillsborough. Of the families, he says: "They are the most experienced lawyers in the country. They may not be formally trained as lawyers but because they've had to fight for justice for over a quarter of a century they know this aspect of the law very intimately. I've seen that extraordinary combination of both dignity and determination. This is not the end. The investigations are ongoing. And that resilience that the families have had to draw on, they're going to have to continue to draw upon it."

Julie Fallon knows that there could still be a long road ahead.

"I don't know what life is like without Hillsborough. It's been so formative, it's been my entire adult life. Andrew has been spoken about every day for 27 years."

For Charlotte Hennessy the inquests have brought answers, and a kind of closure. "I do think that my dad can rest in peace now. There's bits I'll never know, and I'll never find out but I do think he can rest in peace, definitely."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

All images subject to copyright