Hillsborough disaster: Five key mistakes

- Published

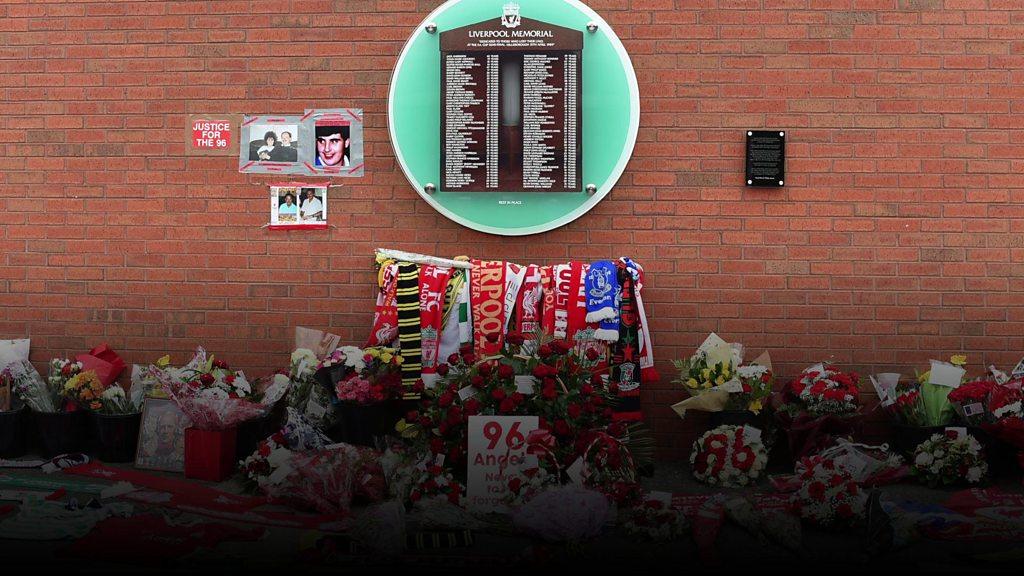

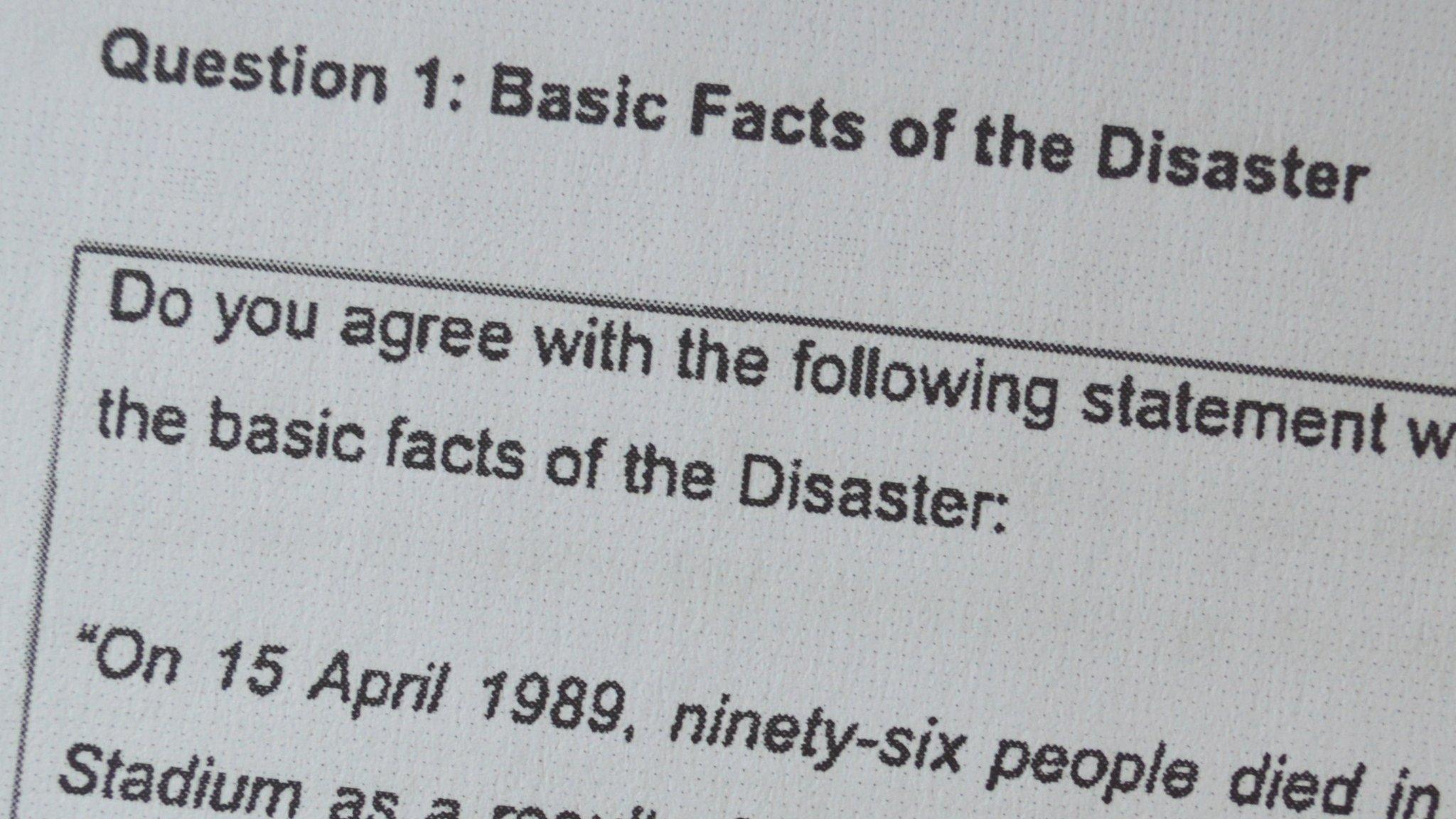

Ninety-six fans died in the Hillsborough disaster, but the inquests heard their deaths could have been prevented if authorities had not made a number of mistakes. BBC News takes a look at some of the key decisions and failures.

1. Failure to prevent crowd congestion

As fans arrived at the Leppings Lane end, congestion quickly grew and police lost control of the crowd

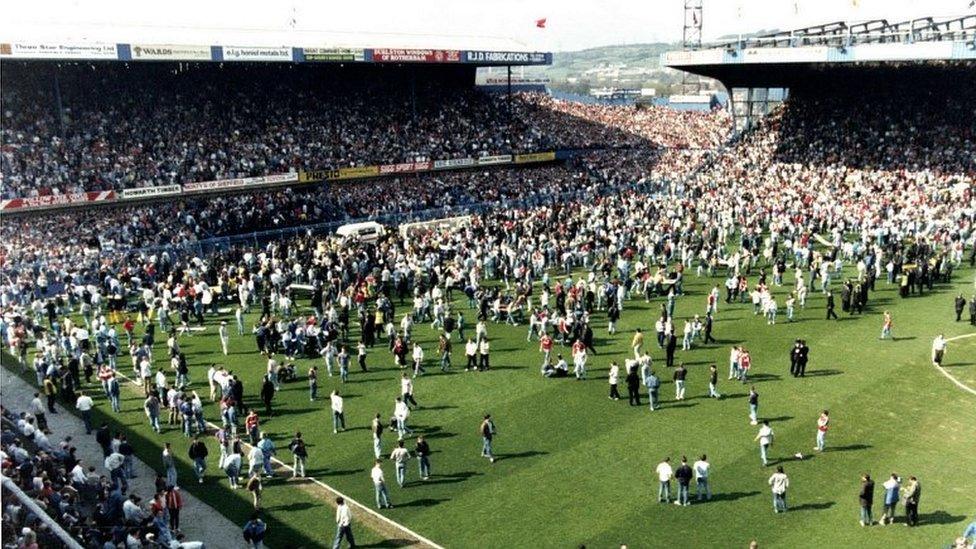

In the half-hour before kick off, the approach to the Leppings Lane end quickly became congested. The 10,100 fans with standing tickets were expected to enter the ground through just seven turnstiles and by 14.30, fewer than half were inside. As more and more fans arrived, the crush at the front of the queue became worse - leading to the fateful decision to open the gates. The inquests heard this was the result of a number of failings.

Firstly, there was no police cordon on the approaches to the stadium to ensure fans formed "orderly queues or only those with tickets came near the ground"., external At the previous year's FA Cup semi final at the stadium, police cordons were in place regulating the entry of supporters. However, there were 172 fewer officers on duty on the day of the disaster. The police match commander, Ch Supt David Duckenfield, admitted in evidence that he should have given "serious consideration to cordons"., external

Police had also closed some turnstiles to keep Liverpool and Nottingham Forest fans apart. This decision - and the design of the approach to the stand - combined to make the congestion worse. The number of fans passing through each turnstile was three times higher than at other turnstiles in the stadium, an HSE investigation, external found in 1990. The Hillsborough Independent Panel (HIP), set up to oversee the release of documents relating to the disaster, concluded there was "clear evidence in the build-up to the match, both inside and outside the stadium, that turnstiles serving the Leppings Lane terrace could not process the required number of fans in time for the kick-off."

The area outside the Leppings Lane turnstiles was described as a "death trap" by former South Yorkshire Police inspector Gordon Sykes. He told the inquest the layout of the turnstiles had previously caused problems and the access route outside the ground meant fans would get "trapped" in corners or against fences and gates. "Up to 1989, I'm going to put it bluntly - we got away with it," he said. Criticism of the turnstiles was rejected by Sheffield Wednesday club secretary Graham Mackrell who said the number of turnstiles for the Leppings Lane terrace had proved "satisfactory" at previous games.

Inside the ground, "there was no means of counting" the number of fans entering individual pens. This made it harder to prevent certain pens inside the standing areas becoming too congested.

The inquest jury blamed police failures before and on the day of the tragedy. It noted that a road closure in the area had exacerbated the situation. No contingency plans were made for the sudden arrival of a large number of fans and attempts to close the stadium's perimeter gates, before fans reached the turnstiles, were made too late.

As the congestion grew worse near the turnstiles and mounted officers struggled to keep control, a radio request was made for reinforcements at 14.44. Some 2,000 Liverpool supporters were still outside and Ch Supt Duckenfield gave the fateful order to "open the gates", letting fans into the ground.

2. Not closing the tunnel

The tunnel leading to the central pens on the Leppings Lane terrace where 96 people suffered fatal injuries in the Hillsborough disaster

As Gate C was opened, most of the 2,000 fans headed straight down a tunnel towards the full central pens, creating the fatal crush. However, if the tunnel had been closed, fans would have been diverted towards the relatively emptier side pens, the inquests were told. This was a recognised method of restricting access to the central pens and had previously been used during the 1988 FA Cup semi-final.

Mr Duckenfield agreed his failure to close the tunnel "was the direct cause of the deaths of 96 people". The jury heard he had at least three minutes to "consider the consequences" of opening the gates. However, Mr Duckenfield admitted he did not think about closing the tunnel but "froze" because of the pressure he was under. In mitigation, he said he was working from a "deficient" set of police orders, which made no reference to closing the tunnel.

Lord Taylor, in his 1990 report into the disaster, considered it "unfortunate" the 1988 closure "seems to have been unknown to the senior officers on duty at the time"., external However, statements seen by HIP suggested that both Ch Supt Duckenfield and his predecessor, Ch Supt Brian Mole, were aware that the tunnel could be used to prevent overcrowding.

Lord Justice Taylor, in his 1990 report into the disaster, had concluded the failure to close the tunnel was "a blunder of the first magnitude". The original investigation by West Midlands Police also concluded "failure to anticipate" that fans entering through exit Gate C and down the tunnel would lead to a sustained crush had a "direct bearing on the disaster".

The inquest jury said commanding officers should have ordered the closing of the central tunnel and their failure to do so caused, or contributed to, the fatal crush on the terrace.

3. Not delaying kick-off

The match was eventually stopped at 3.06pm by Supt Roger Greenwood who ran on to the pitch

As match commander, Ch Supt David Duckenfield had it in his powers to delay the kick-off in the interests of crowd safety. At about 14.30, TV monitors in the police control room clearly showed the numbers at the Leppings Lane end were growing. But, after discussing the postponement with his deputy, Supt Bernard Murray, Mr Duckenfield decided the game should go ahead on time. Under questioning at the inquests, Mr Duckenfield said he now accepted he should have delayed the kick-off.

Supt Roger Marshall, who was stationed at the Leppings Lane entrance, told the jury of his "profound regret" at not requesting a delayed kick-off. He agreed it would have alleviated "the anxiety and frustration" of supporters trying to get into the ground.

The decision was dealt with by the original Taylor inquiry into the disaster. Lord Justice Taylor concluded that, faced with a situation which was becoming dangerous, "crowd safety should have been Mr Duckenfield's paramount consideration", external. Kick-off should have been delayed which would have given time to relieve the pressure at the turnstiles, he said.

Glen Kirton, the Football Association's press chief in 1989, told the inquests he raised the possibility of a delayed kick-off with Sheffield Wednesday secretary Graham Mackrell. He said he asked Mr Mackrell whether, with 20,000 people yet to enter ground, the police may request a delay. He said he was told "they did not like to do that because of the potential problems that caused at the end of the game with getting spectators away." However, Mr Mackrell denied discussing any possibly delay with Mr Kirton and told the jury it was "a problem for the police to deal with". He said any delay was a decision for the match commander, external

Mr Duckenfield had previously told the Taylor Inquiry, external a delay would only be ordered "if there was some major external factor such as fog on the Pennines or delay on the motorway: not if spectators merely turned up late even in large numbers." But the kick-off had been delayed two years previously; the 1987 semi-final was postponed for a quarter of an hour because of late arrivals.

As the teams ran on to the pitch for the 15.00 kick-off, the HIP report, external said "the crowd cheered but already in the central pens people were screaming. Others fell silent, already unconscious". At 15.06, the match was stopped by a police officer walking on to the pitch.

4. Slow emergency response

Only three South Yorkshire ambulances made it onto the pitch in the aftermath of the Hillsborough tragedy

The original Hillsborough inquests did not consider the response of the emergency services because the coroner, Dr Stefan Popper, controversially ruled out evidence from after 15.15 on the day of the disaster. His decision, later overturned, was based on the flawed assumption that all the victims were dead or fatally injured by this point.

However, the resumed inquests heard the response by emergency services had been "woefully inadeqate". David Whitmore, an expert in pre-hospital care, criticised a senior ambulance officer, Paul Eason, for failing to look inside the pens, even though a major disaster was unfolding in front of him.

Mr Eason was described by South Yorkshire Ambulance Service chief Albert Page as its "eyes and ears" at the stadium. However, he said he was unaware spectators were being crushed. He accepted he "failed to properly assess the situation" and "failed to declare a major emergency at the earliest opportunity". However, he said his radio had been faulty at the time. Asked whether he thought of alerting nearby hospitals, he said he had presumed the ambulance control room would do so.

Mr Whitmore said while the ambulance service response was delayed, volunteers from St John Ambulance "behaved better" than their counterparts by starting to help victims immediately. There were "misunderstandings and failures" in communication between the emergency services, he added. Bolt cutters, requested at 15.10 from the police garage, did not arrive until after all the injured had been removed. One doctor helping casualties on the pitch asked a police officer for oxygen equipment to resuscitate a stricken supporter. When he was passed a cylinder, it was empty, the jury was told.

Prof John Ashton, a public health expert who was at the match as a Liverpool supporter, told the inquests he led the assessment of casualties behind the Leppings Lane end because no-one else was taking charge. "It was just chaos," he said. "There were lots of casualties, there were a certain number of police, there was no evidence of any health service people."

At least one fan who died could have been saved with prompt medical attention. Dr Jasmeet Soar, a resuscitation specialist, said "earlier intervention before cardiac arrest" could have saved the life of James Aspinall, son of Hillsborough campaigner Margaret Aspinall.

Following a police request for a "fleet of ambulances" at 15.06, 42 front-line ambulances lined up outside the ground but access was delayed because police were reporting "crowd trouble". There was a "lack of the basic necessary life-saving equipment on the pitch where it was most needed", said the HIP report. Only two ambulances reached the Leppings Lane end of the pitch and of the 96 people who died, only 14 were ever admitted to hospital.

Mr Eason did not declare a major incident until 15.22. Chief ambulance officer Albert Page said this was "too long" a delay. He criticised Mr Eason for failing to assess the situation and prioritising a casualty with a broken leg. Mr Page said he initially thought the ambulance response was "speedy and efficient" but said the inquest hearings had led him to revise that view.

He said: "I think the weak point was activating the major incident call and the assessment by the ambulance staff at the ground, who listened to what they were being told by the police that it was a pitch invasion."

The jury decided the emergency services response had been delayed by the police's own delay in declaring a major incident and said the ambulance service failed to ascertain the nature of the problems on the Leppings Lane terrace.

5. Lessons not learned

Hillsborough inquests: Jury shown 1981 footage

In 1989, Hillsborough was deemed to be one of most advanced stadiums in the UK. It had been chosen to host FA Cup semi-finals in 1981, 1987 and 1988. It boasted state-of-the-art CCTV and a turnstile counter system to monitor fan numbers entering the ground. Yet it had been the scene of dangerous crushes on a number of occasions. The jury were told one incident, in 1981, was a "near miss", external. However, lessons about the unsafe nature of the stand were not learned.

According to John Cutlack, an expert stadium engineer, the seeds of the 1989 disaster were sown 10 years previously when a safety certificate overestimated the capacity of the Leppings Lane standing area at 7,200. He said the true safe figure was in fact 5,425. Pen three, where many Liverpool fans died, could only safely hold 678 fans but on the day of the disaster there were up to 1,430 people inside. The club's engineer, Dr Eastwood, agreed "with hindsight" the total figure of 10,100 - which allowed for an additional 2,900 standing fans in the north-west corner stand - was "too high".

In 1981, at the semi-final between Tottenham Hotspur and Wolverhampton Wanderers at Hillsborough, 38 fans were injured in a crush. In a course of events that would be repeated eight years later, police opened Gate C after congestion at the turnstiles. A serious crush developed in the Leppings Lane end and fatalities were "narrowly avoided", external, according to the HIP report. Two perimeter gates were opened to let some fans escape on to the pitch. Turnstile counters showed that 335 too many fans had been allowed on to the terrace that day. At the time, Sheffield Wednesday FC blamed Tottenham fans for "arriving late" and "rushing to their places", external, crushing those in front. After the incident, Hillsborough was not chosen to host an FA Cup semi-final for six years.

Under the terms of the ground's safety certificate, an Officer Working Party including the council, police, fire service and the club, inspected the ground each year. But the OWP never flagged up that the capacity of the Leppings Lane terrace needed recalculating. When it reviewed the stadium in May 1988, the OWP said the stadium had "no significant defects". Mr Cutlack told the inquests the annual inspections of the ground were missed opportunities to reassess the capacity.

The Leppings Lane terrace then underwent some significant alterations, none of which led to a revised safety certificate, external. On the recommendation of South Yorkshire Police, the club introduced the penning system to "prevent free movement of supporters". Yet proposals to feed fans directly to certain sections of the stand from designated turnstiles, allowing numbers to be monitored, were not acted on "because of anticipated costs to SWFC", external, the HIP report found. The gradient of the tunnel also significantly breached guidelines for sports grounds.

Reinstated as a semi-final venue in 1987, Hillsborough hosted the match between Leeds United and Coventry City. Shortly before kick-off, police delayed the match by 15 minutes to ensure that late-arriving fans could be accommodated. One Leeds fan described "a bad crush" in the central pens, the crowd so tightly packed, he was "unable to clap his hands", external.

The 1988 semi-final, also between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest, passed without serious incident although some Liverpool fans and police officers later gave accounts of crushing within the Leppings Lane pens. On this occasions, the tunnel was closed and fans redirected to the side pens. According to the HIP report, Sheffield Wednesday "denied knowledge of any crowd-related concerns, external arising from the 1987 or 1988 FA Cup semi-finals".

It said overcrowding problems at the turnstiles in 1987, and on the terrace in 1988, indicated the inherent crowd safety dangers posed by the ground. The risks were known and "the crush in 1989 was foreseeable", external, it added.

The jury concluded there were too few operating turnstiles, signage to the side pens was inadequate and the stadium design and layout contributed to the crush.

- Published26 April 2016

- Published24 April 2016

- Published26 April 2016

- Published26 April 2016

- Published24 April 2016