Identity 2016: Why I stopped mispronouncing my Igbo name

- Published

In Nigeria, the language spoken by one of the largest ethnic groups, the Igbo, is in danger of dying out - which is odd because the population is growing. In the past this didn't worry the BBC's Nkem Ifejika, who is himself Igbo but never learned the language. Here he explains why he has changed his mind.

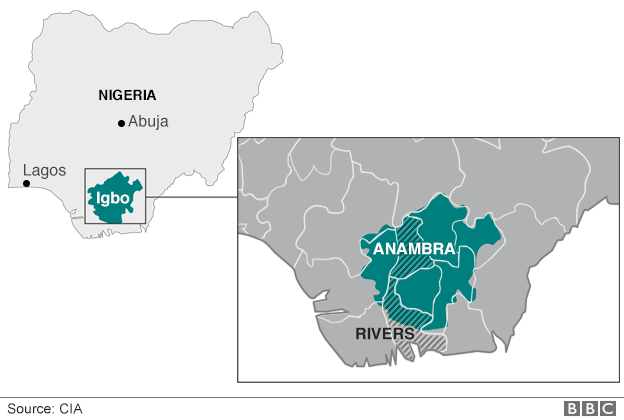

When I'm in Nigeria, I say my dad is Igbo from Anambra State, and my mum is from Rivers State. I might throw in that I partly grew up in the United Kingdom.

In Britain, I say I'm Nigerian, though I often add explainers about having been educated at British schools and lived outside Nigeria since I was 12 years old.

When visiting other countries though, I identify myself as British - occasionally adding "via Nigeria", for good measure.

I speak English and French, I can hold conversations in Spanish, and Yoruba and I've formally studied Arabic and German to varying degrees. But I can't speak Igbo, a language which should be very personal to me, the tongue of my ancestors.

If you'd asked me my name 10 years ago I'd have given an Anglicised pronunciation - one I learned from my British teachers and fellow students, rather than the one I learned from my parents.

Listen: Nkem explains how to pronounce his name

Nkem Ifejika (or Nkemakonam Ifejika in full) is an Igbo name from south-east Nigeria, and Igbo is a tonal language. So words with the wrong stresses and tones either change their meaning, or worse, become unintelligible. The word "akwa" can mean crying, cloth, egg, or bridge, depending on how it's said.

In Igboland, as it's informally known, names have meaning and history. Circumstances of a child's birth can determine the name given to a child. Names can be prayers or pronouncements on the child.

Nkemakonam means "may I not lack what is mine", while Ifejika means "what I have is greater". By mispronouncing my names, I was throwing away generations of history, and disregarding my parents' careful choice.

Igbo people

In Anambra, Wednesday is "Igbo day"

One of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria, living mainly in the south-east of the country

Igbo is one of Nigeria's most widely spoken languages along with English, Hausa and Yoruba

In 1967, Igbos tried to secede from Nigeria creating Biafra, an independent nation, but this sparked a civil war which lasted more than two years

Traditional Igbo religion includes belief in a creator god (Chukwu or Chineke), an earth goddess (Ala), and other deities and spirits as well as a belief in ancestors who protect their living descendants

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica

My indefatigable and proudly Igbo wife, Chikodili, rescued me when we met. "You don't even know how to pronounce your name," she'd say, half-teasing, half-scornful. And only half-correct... I did know, I just stuck as a rule to the Anglicised version.

I look back on those days with a hint of shame. But now, when I'm on air, I say my name properly, with the correct tones, and with pride. I can and do forgive other people for getting my name wrong, but I should not be mispronouncing my own name.

Igbos I come across often complain that Igbo children don't speak the language. It's a refrain I hear both in Nigeria and among the Igbo diaspora abroad. They're quick to praise Yorubas and Hausas (the other two large ethnic groups in Nigeria) for teaching their children their mother tongue.

When two Hausas meet, they always speak Hausa, and it's the same when two Yorubas meet. But when two Igbo meet, they may well speak English to one another. These anecdotes are backed up by Unesco's description of Igbo in 1995 as "endangered", a rarity for a language whose population is actually growing.

But why are Igbo people failing to pass on the language to the next generation?

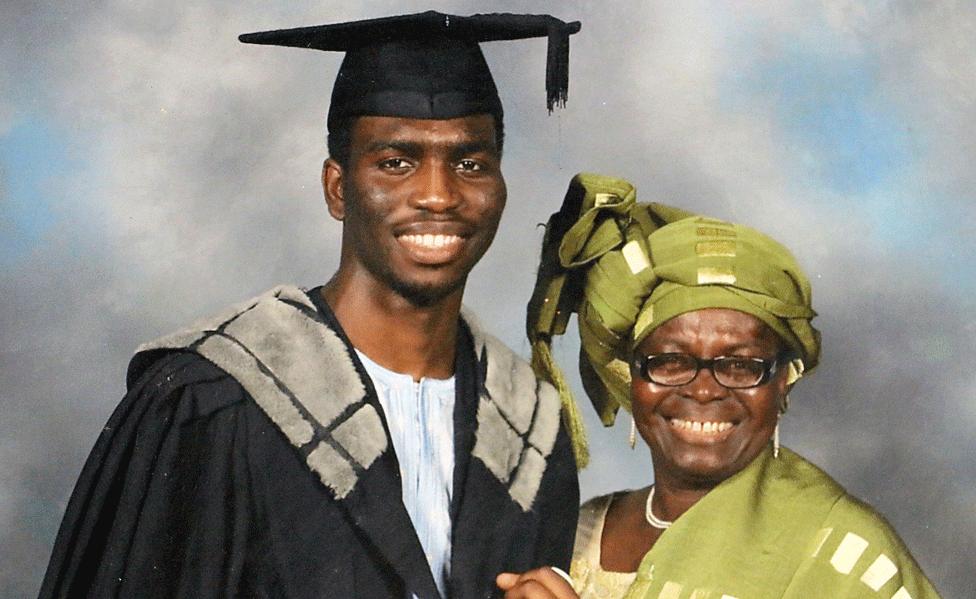

With my mother at my graduation

Even though my mum isn't Igbo she speaks it fluently. As I said, she comes from Rivers State in southern Nigeria, where once Igbo was a kind of lingua franca. But she didn't think it was critical for me to learn it as she wanted me to have an international outlook.

And I cannot fault that pragmatic decision to teach me other world languages, even though my Igbo languished as a result.

It's the same with many other Igbo families. They are outward-looking and aspirational.

Igbos have a reputation for exploring faraway lands in search for a better life. Some complain that we're too quick to assimilate and adopt the culture of the host country, others argue this traveller spirit is something to be proud of. Assimilation isn't always easy, so I give credit to immigrants who succeed in doing so. But distance from homeland takes a toll on the old culture.

Igbo is spoken in the area highlighted green

Storytelling and proverbs are very important to the traditional Igbo way of life, and have always helped to sustain the language. Away from the elders, and away from the village square where the stories are told, it's easy to start losing contact with it. There are some books in Igbo, but no newspapers.

Igbo people have also faced more than just the cultural battering which is the norm in a world where English predominates.

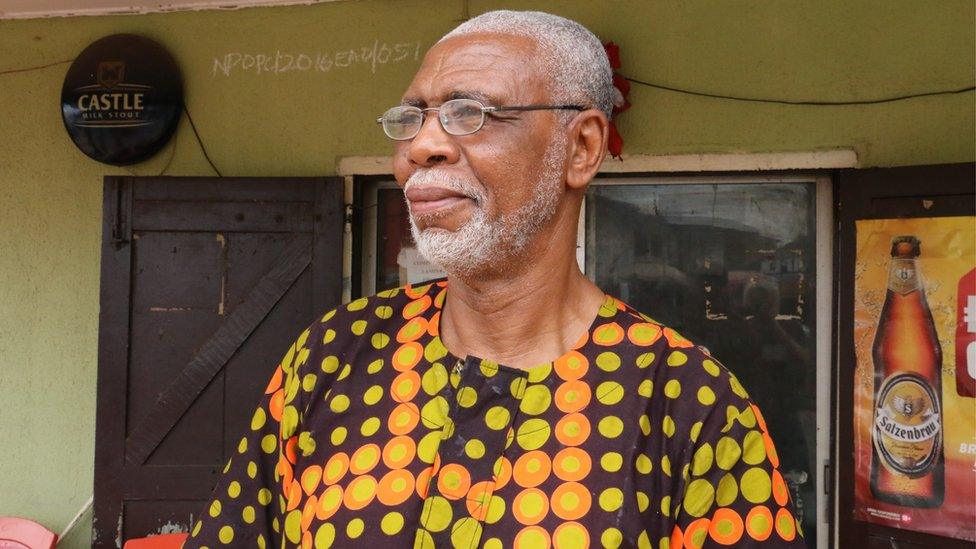

My dad returned to Igboland after decades in Lagos, to live close to our ancestral village in Awka, Anambra State. He feels Igbos are discriminated against within Nigeria, and comes very close to endorsing secession. I tell him many groups within Nigeria feel marginalised, and that such disaffection is not unique to Igbos.

My father Amechi "Don" Ifejika in traditional Igbo dress

Nigeria and Igbos have been here before, and it didn't end well. The Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970) in which the Igbos tried to form a separate state of Biafra saw a million Igbos die, mostly through starvation. After the war ended, the Nigerian government declared "no victor, no vanquished" as a way to bury enmity.

But as a friend told me, the civil war was akin to a child being flogged, but told not to cry.

Emotions are still raw as there's been no closure, no catharsis, and the Biafran war isn't taught in schools.

This continued disaffection has given rise to secessionist groups such as the Indigenous People of Biafra and Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra. While many Igbos I speak to are not necessarily in support of secession, they see these groups as standing up for Igbo rights.

Nkem Ifejika

Born in London, holds dual British and Nigerian citizenship

Presents Newsday on BBC World Service Radio

Thirty-five years old

All these issues are interlinked, fear of marginalisation, identity crises, an endangered language.

After the war, Igbo lost its status as a lingua franca that non-Igbo people like my mother would learn.

While growing up, I didn't care that I couldn't speak Igbo, but in adulthood, especially since becoming a father, it's something I want to fix. I find myself wanting to bequeath Igbo to my son, Anyikamba (the name means "we are greater than a nation"), as an invaluable inheritance.

I don't yet know as much as I should about my ancestors, or enough about Igbo history, so I can't pass these on to him. But language as an embodiment of that living, breathing, history, I (and especially my wife) can give.

My identity is fairly cosmopolitan and outward looking, and I'm very adaptable. I've never been anywhere where I felt, "there's no way I can live here".

The global languages I speak are probably more in keeping with my outlook, so why would I want to speak a language which restricts me to 41,000 sq km in the south-east Nigeria?

I think it's because the modern world is so fluid, and multiple identities are more possible than ever before, that I want something rooted and preserved in time.

And for me, that's Igbo.

As people become increasingly connected and more mobile, the BBC is exploring how identities are changing.

Listen to and download programmes from the World Service's Identity season.

Learn more about the BBC's Identity season or join the discussion on Twitter using the hashtag #BBCIdentity, external.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published2 April 2016

- Published11 April 2016

- Published31 March 2016