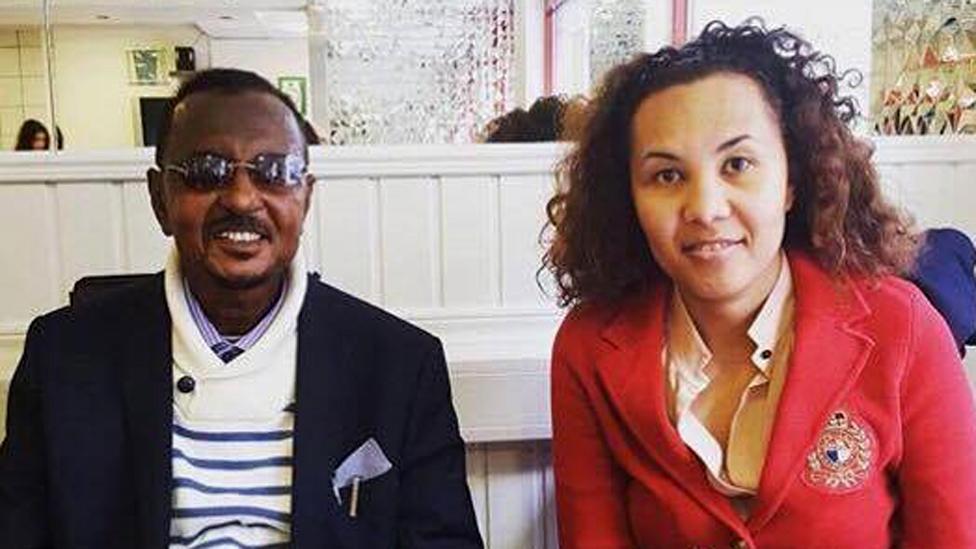

'I found my dad on Facebook'

- Published

•Farhiya was separated from her father when she was a baby

•She didn't see him for nearly 40 years

•They were reunited thanks to a stranger on social media

"Congratulations! We found your dad!" read an email in Farhiya's inbox.

"I couldn't believe it when I first got the news." she says. "It was a dream come true. But I always kept faith this moment would one day arrive."

When she was growing up, Farhiya used to ask her mother what her dad was like.

"She would tell me to look in the mirror," says Farhiya. "You talk like him, you walk like him, you even argue like him," her mother would reply.

But apart from a few black and white photos, that was all she had to go on.

Thirty-nine-year-old Farhiya was born in Leningrad - now St Petersburg - in 1976 to a Russian mother and a Somali father.

Farhiya learned about her father (standing far right) through old photographs

Siid Ahmed Sharif was one of many young Somali officers invited to study in the Soviet Union as the USSR sought to expand its influence in Africa.

He and Farhiya's mother planned to marry, but a year after Farhiya was born, Somalia went to war with its neighbour, Ethiopia - and the Kremlin sided with Ethiopia.

So very soon Somalia expelled Soviet advisers from the country and all Somali students in the USSR, including Farhiya's father, were told to go home.

"My mum and I were visiting my grandma in Western Siberia when we first heard on radio about the war," she says.

"I remember her telling me later that she immediately knew what this meant for our family, what this meant for my father."

Sharif had 24 hours to pack his bags. With his loved ones away, he couldn't even say goodbye but he left a note with his parents' address in Mogadishu.

"I knew he did not walk out on us, he had not left us or abandoned us," says Farhiya. "He only left us because of the circumstances."

But those circumstances also made it impossible to stay in touch.

The family was separated for nearly four decades.

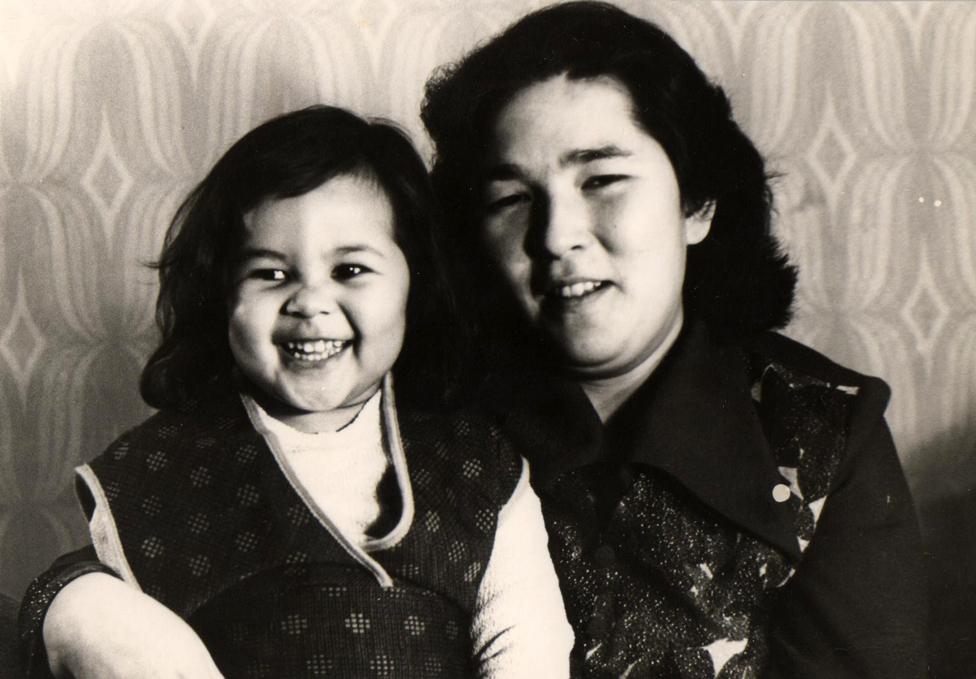

Farhiya as a child with her mother

Despite this, Farhiya's childhood was a happy one.

"I was surrounded by unconditional love from my mum. Her relatives gave me so much love and care, I felt very special," she says.

"I was proud of my heritage, was proud of looking different… My classmates, my teachers at school and the university always told me I was special."

Farhiya spoke to World Update on the BBC World Service - listen to the interview here

Farhiya always wondered where her father was and what he was like, though.

"The desire to find my dad was always there but it was when I was about 12, I thought to myself I had to do something to find him," she says.

By this time the political climate had changed - Mikhail Gorbachev's policy of glasnost (openness) was under way and Farhiya saw nothing to stop her writing to her father.

But when she sent letters to the address he had left they always bounced back unopened. She didn't know if they even reached Somalia.

She contacted organisations in the USSR that helped children find their African fathers and got in touch with the Red Cross, which provided a similar service. But her attempts were fruitless.

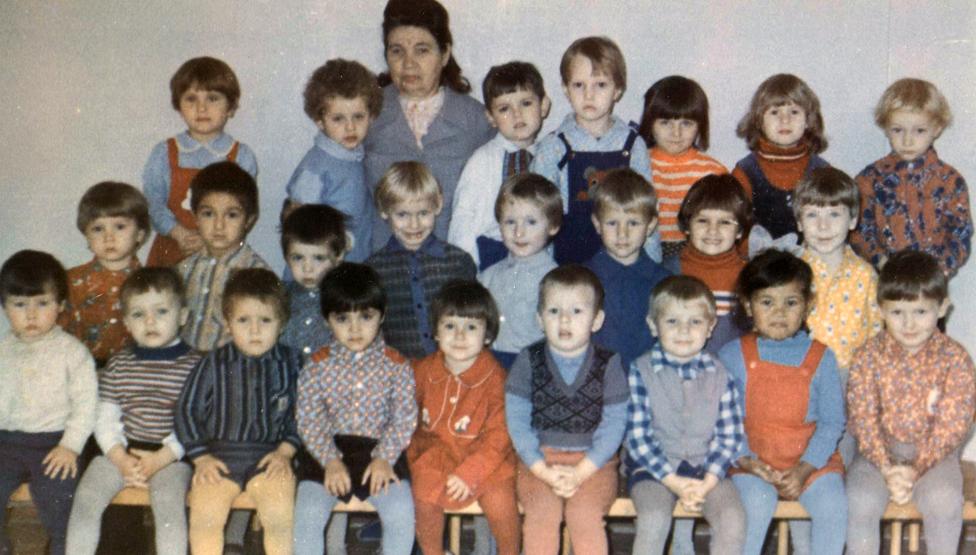

Farhiya as a child with her classmates (front row, second from right)

"Other Russian children were able to find their parents in other African countries because it was easier. Those countries had diplomatic relationships, embassies and people working in Russia who were going back and forth to African countries. As for Somalia, access was extremely limited," she says.

From time to time she stopped actively searching but she never fully let go of the idea of finding her father.

"It was like trying and failing and then giving up for few years then going back to the search once again and failing again," she says.

When Somalia descended into civil war in 1991, that was a huge setback.

The war continued for nearly two decades, but as it drew to an end, social networks were beginning to emerge and this gave Farhiya fresh hope.

On one Russian social media site, Vkontakte, she came across a woman helping reunite people with parents living abroad, but it turned out to be another dead end.

"I wrote to her but she said that if my father was in Somalia she would not be able to help," Farhiya says.

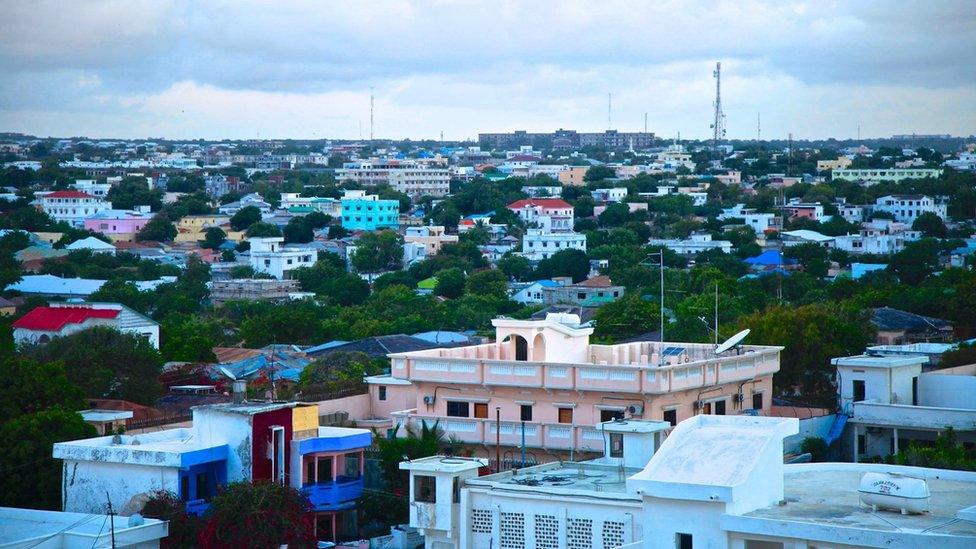

Then she started to browse pictures of Somalia on Instagram.

A photograph of Mogadishu posted by Deeq M Afrika on Instagram

A lot of the photos she liked were posted by a young Somali man called Deeq who seemed well connected, so she messaged him to see if he could help.

Deeq had cultivated a range of Somali contacts during his years travelling in North America, Europe and the Horn of Africa. He also had good contacts in the Somali government from his work at the country's embassy in Dubai.

On 16 March he posted Farhiya's plea on his Facebook page.

Comments soon started flooding in, and one from Norway stood out.

"That's our sister Farhiya," it read.

It was written by one of Farhiya's half siblings, living in Oslo, and her father was staying with her at the time.

A picture of Farhiya's father which was posted with the message

A few weeks later, after several Skype calls, Farhiya, her mother and Farhiya's husband travelled to Norway to meet her father.

"He was exactly like I expected him to be," she says. "We walked exactly in the same manner. We talked exactly in the same voice. It was unbelievable - the two of us were together after all this time!"

She met three of her half-sisters, and a half-brother arrived from Sweden, where her father lives most of the time. A half-uncle also flew to Oslo for the family gathering.

Farhiya discovered that her father had been looking for her too.

"When we spoke on Skype for the very first time, he told me about his attempts to reach us," she says.

But she and her mother had moved when her mother had married, and Sharif didn't have their new address. And like his daughter, he had run up against problems caused by the breakdown in relations between their two countries.

These days Farhiya and her mother talk regularly with Sharif on Skype and another meeting is planned. Next time he may visit St Petersburg.

There are many things about her father's life Farhiya has yet to find out, and many things she and her mother want to tell him about the last four decades.

Fortunately Sharif still remembers the Russian he learned many years ago.

Farhiya is delighted to have discovered an extended family in Scandinavia and Somalia, but sometimes it's hard to take in that her search is finally over.

"It will probably still take me a long time to believe that in my phone, I now have the most important contact in my life - Dad."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

- Published2 January 2024