The Unabomber and the Norwegian mass murderer

- Published

A recent legal wrangle about the human rights of a mass killer has raised questions about the right to advocate violence. Benjamin Ramm sees parallels with the case of the Unabomber, a man who has fascinated America for decades.

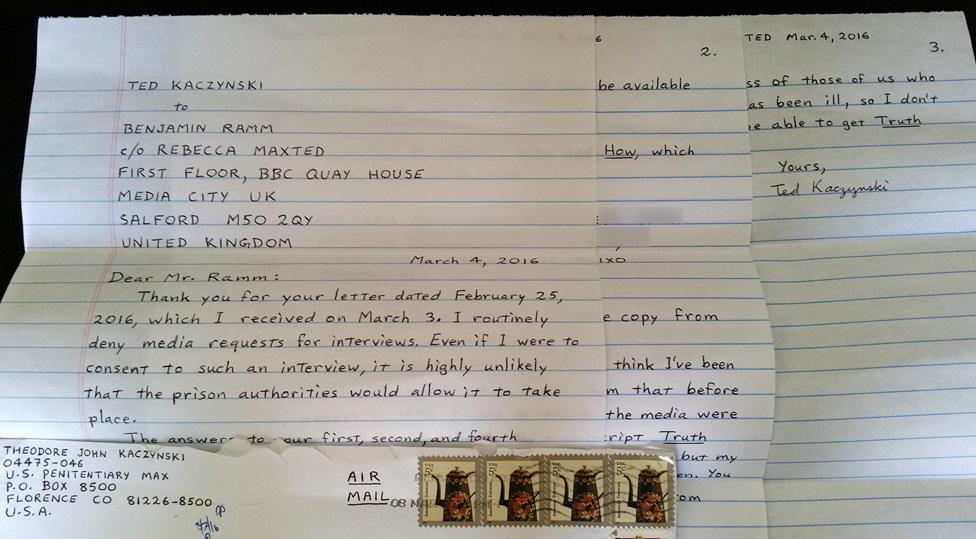

It arrived, quite unexpectedly, in a nondescript envelope with carefully inscribed childlike handwriting. The name of the sender, listed in the top left-hand corner, immediately caught my eye: Theodore Kaczynski, known as the Unabomber, had sent me a letter.

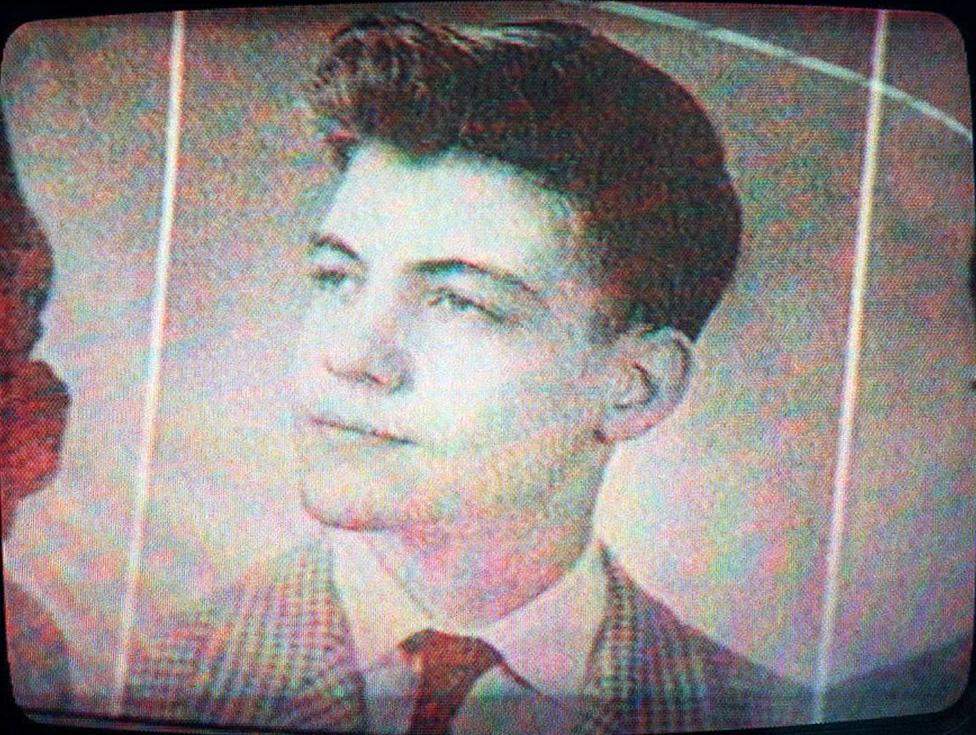

During a 17-year campaign of terror, Kaczynski placed or posted 16 home-made bombs, which killed three people and injured 23. The FBI gave him a pseudonym: UNAbomber - a reference to the universities and airlines he targeted.

For years, investigators had few clues to go on, as the bomber meticulously concealed his identity. He left only a signature carved inside a bomb - FC, later revealed to stand for "Freedom Club".

Theodore Kaczynski's letter to Benjamin Ramm

But in 1995, the year before he was arrested, America's two most prestigious newspapers, the Washington Post and the New York Times, agreed to publish his anonymous 35,000-word manifesto, under the threat of further violence. In it he called for the destruction of the "industrial-technological system", which in his view robbed individuals of their freedom.

I had written to Kaczynski, now serving eight life sentences at a high security prison in Colorado, after interviewing key figures in this story: his victims, his only brother (who tipped off the FBI after reading the manifesto), and the former publisher of the Washington Post. Kaczynski no longer grants media interviews, but communicates with various "penpals" - an extraordinary correspondence now archived in the library of the University of Michigan, where Kaczynski gained his PhD in mathematics.

I asked Kaczynski whether he felt any contrition for his acts: in response, he directed me to an essay he had written on morality, arguing that it is a tool of oppression employed by "the system". He has displayed no remorse or sympathy for his victims, and has even taunted some of those he maimed. And he continues to justify the use of violence for political ends.

The right of a prisoner to advocate violence in written correspondence is now at the heart of a legal dispute involving a man inspired by Kaczynski: the Norwegian Anders Behring Breivik, who murdered 77 people and injured 319.

In the hours before his attacks in 2011, Breivik disseminated a 1,500-page manifesto that copied numerous passages from the Unabomber's own work, without attribution and with some substitution - "leftism" was changed to "multiculturalism", and "blacks" to "Muslims".

Manifestos compared

Kaczynski: One of the most widespread manifestations of the craziness of our world is leftism, so a discussion of the psychology of leftism can serve as an introduction to the discussion of the problems of modern society in general.

Breivik: One of the most widespread manifestations of the craziness of our world is multiculturalism, so a discussion of the psychology of multiculturalists can serve as an introduction to the discussion of the problems of Western Europe in general.

Kaczynski: But what is leftism? During the first half of the 20th century leftism could have been practically identified with socialism. Today the movement is fragmented and it is not clear who can properly be called a leftist.

Breivik: But what is multiculturalism or Cultural Communism? The movement is fragmented and it is not clear who can properly be called a cultural Marxist.

Kaczynski: Political correctness has its stronghold among university professors, who have secure employment with comfortable salaries, and the majority of whom are heterosexual, white males from middle-class families.

Breivik: Political correctness has its stronghold among government employees, politicians, university professors and journalists and publishers in government broadcasting companies who have secure employment with comfortable salaries, and the majority of whom are heterosexual, ethnic Europeans from middle-class families.

Like many "lone wolves", both men imagined themselves as part of a wider community: Kaczynski's "Freedom Club" promised to liberate the world from technology, while Breivik adopted the grandiose title of Jesticular Knight of the Knights Templar, imagining himself as "the point of the spear to eliminate the Muslim invasion of Europe", according to terrorism expert Dr Jerrold Post.

Unlike the Unabomber, Breivik is not a technophobe: in his cell he has an X-box, a PlayStation, and a laptop.

Last month a Norwegian court ruled that his human rights had been infringed under Article 3 of the European Convention. Breivik's freedom to associate with other prisoners has been restricted after he vowed to convert them to his cause, and he has spent much time in solitary confinement. But the court also ruled that the prison had not violated Article 8 of the Convention, in relation to the confiscation of a small portion of Breivik's correspondence. More than 4,000 letters have been sent to or from the prisoner, of which about 600 have been confiscated, because they were deemed to encourage violence.

Post tells me that Breivik "was admiring of the accomplishment of the Unabomber in coercing an audience for his thoughts". Breivik claims that he committed murder to promote his message, and echoed the Unabomber's statement that in order to make "a lasting impression, we've had to kill people".

Breivik also used his trial as a platform from which to broadcast his ideology. The propaganda of political violence poses difficult questions for media outlets - as demonstrated by recent coverage of the so-called Islamic State. In America particularly, commercial cable networks have exacerbated the problem, as ratings-based competition has further sensationalised violence ("if it bleeds, it leads").

Post describes terrorism as "a vicious species of psychological warfare waged through the media", and says that the Unabomber's demand for the publication of his manifesto left the press with "a rather extreme version of the academic dictum: publish or perish". That decision was made jointly by Donald Graham, the publisher of the Post, and his counterpart at the Times, Arthur Sulzberger, with advice from the FBI. Graham tells me that he was not overly concerned about setting a precedent, and feels that the decision to publish was vindicated, as it led to Kaczynski's identification and arrest. But not all in the media shared his confidence: "It is blackmail, pure and simple, to which the Times and the Post have acceded", argued the host of ABC's Nightline programme on the day of publication.

Find out more

You can listen to Terror and Technology: The Unabomber on Sunday 29 May, on the BBC World Service. Or catch up afterwards on the BBC iPlayer.

In the tabloid press, a diagnosis of mental illness is often regarded as an avoidance of punishment, but in the case of political violence, it has a disarming quality: it shatters the illusion of grandeur and deprives the act of ideological significance. Both Kaczynski and Breivik knew this, and fought passionately against their diagnoses of paranoid schizophrenia - in Breivik's case successfully. Breivik said that to be treated in a psychiatric ward would be a "fate worse than death… To send a political activist to an asylum is more sadistic and more evil than killing him". After Kaczynski learned that his legal team was pursuing a mental health defence, and that he could no longer dismiss his lawyers, he attempted to commit suicide in his cell. This highlights why imprisonment can be more punitive than capital punishment: Kaczynski would have preferred to die for his ideas, rather than live without access to wild nature.

Kaczynski idealised hunter-gatherer civilizations, and once told his brother David that "he wished at times he was the only human being alive". For 25 years, he lived in almost complete self-sufficiency in a small cabin in rural Montana, with no running water, heating or electricity. Kaczynski was removed from the consequences of his actions - he could express his venom with the luxury of anonymity, much like a troll on social media. But by publishing his manifesto, the mainstream media gave him notoriety, propelling his personality into the public arena.

Exposure is no guarantee of success, however, and two decades later Kaczynski's goal of a society free of technology is further away than ever. This does not mean that the issues he addressed are no longer relevant: earlier this year, a major conflict between Apple and the FBI over the right to extract data from an iPhone, highlighted the complex relationship between technology, security and liberty. But David Kaczynski, the Unabomber's brother, tells me that "because of the violence, people don't hear the questions very well: it's like the question is lost in the sound of the explosion".

Yet there remains a cult fascination with the Unabomber - one that Breivik sought to replicate. Shortly after Kaczynski's arrest, in the early days of the internet, Time Warner's website asked: "Is there a little of the Unabomber in all of us?" In 2013, Fox News online ran an article headlined: "Was the Unabomber correct?" Today, you can visit Kaczynski's cabin - it's on display at the Newseum in the heart of Washington DC.

Throughout his life, Kaczynski has been obsessed with one book - The Secret Agent by Joseph Conrad. He has read it dozens of times and kept a copy in his cabin in Montana. Both he and the author have Polish roots, and Kaczynski used formulations of Conrad's name ("Konrad", "Konzeniowski") as an alias to escape detection.

Kaczynski identified with the anarchist professor in the novel, whose contempt for the weak and disdain for society allow him to rationalise terrible violence. But he misread Conrad's intention: the book is a dark satire, critical of the cold calculation that justifies murder. The author knew what Kaczynski still doesn't acknowledge: that violence is a failure of the imagination.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.