How I convinced the world you can be raped by your date

- Published

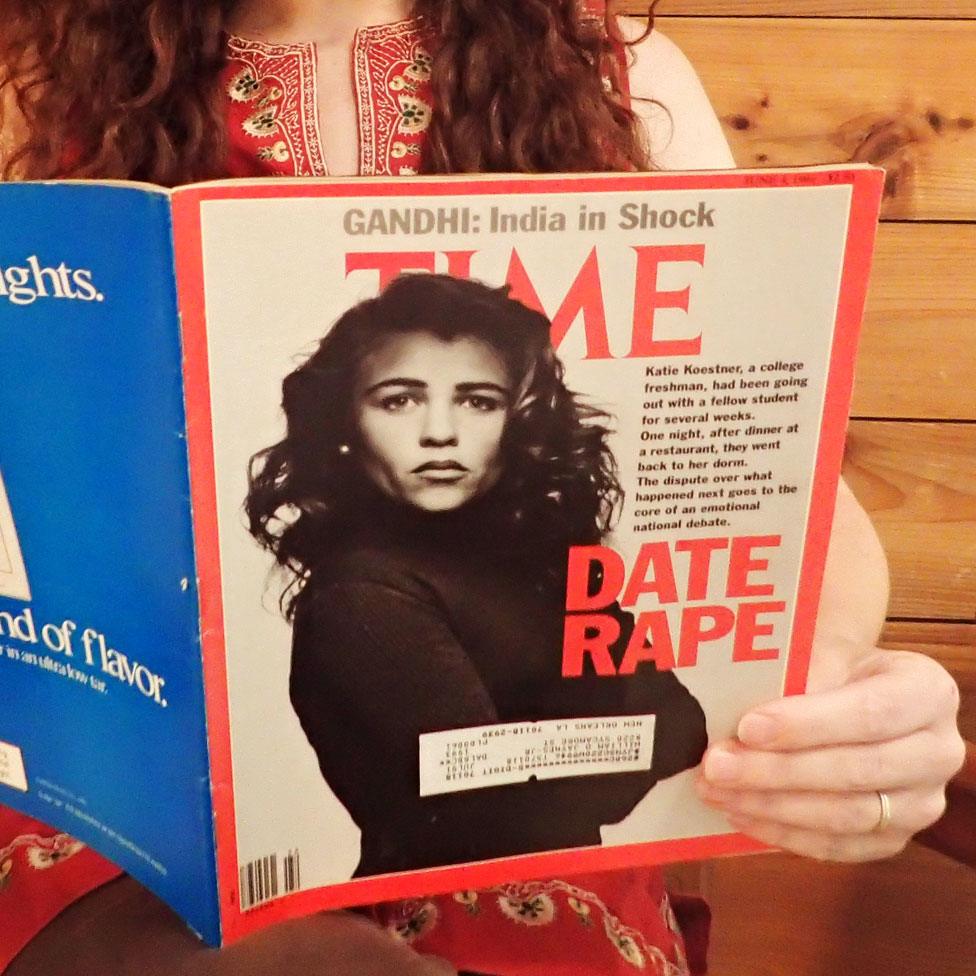

Katie Koestner was on the cover of Time Magazine on 3 June 1991

Katie Koestner was 18 when she went on a date with a fellow college student - and was forced to have sex. In 1990 the idea that you could be raped on a date was not widely understood, but Koestner went public with her story and - as she explains here - the concept of "date rape" took root for the first time. Some readers may find her account disturbing.

I grew up in Atlanta, Georgia. I had a younger sister, a full-time mom, and my dad was an FBI agent. I swam every day, played piano and loved books. I guess I had a fairly sheltered upbringing but I grew up loving life.

At 18 I went off to college to study chemical engineering and Japanese. I chose the College of William & Mary in Virginia, which oozed history. I decided to live on campus in a women-only residence hall. I threw myself into campus life, joining a band and a church youth group.

In the first week I met a guy. I thought he was amazing-looking, and luckily he had the talent to match. I wasn't naive but I was a romantic at heart. I thought you were lucky if you met the right prince.

He asked me out for dinner. It was pretty rare to eat off campus so I was really excited to go. We went to a fancy restaurant with candles and live music. The waiters spoke French, my date ordered in French, and I couldn't believe my good fortune. I felt I'd met the best guy in the whole campus.

After dinner I didn't want to go back to his room. I thought maybe his room-mate might be there, or alcohol - I didn't want to drink.

But I never thought there was anything weird about having some guy come to your room, just to hang out. There was no, "OK the door to your room has opened and you've turned on the green light for everything the guy might want."

On my ceiling I had the constellations of the night sky. I said, "Let's dance under the stars." It was romantic and silly. I was 18 years old.

Then I remember he was trying to undo the buttons on the back of my dress. They were fancy and tricky and I was thinking, "Oh no he could break my dress."

I didn't think about my own safety because I was out with a great guy. I was just thinking I have to get him to stop doing that, so I pushed him away gently.

He stopped and moved to the other side of room. I glanced into the mirror and saw him taking off his clothes and thought. "Oh no." And then, "Oh wow," because he was so handsome.

I basically had a feminist epiphany all in one minute. I went from, "That's too fast for a good girl," to "Do I have to be a good girl?" to "What is a good girl, and why is it not the same as a good guy?"

But my final verdict was, "I need to get him to stop taking off his clothes," so I grabbed my stuffed animals and threw them at him, laughing.

Suddenly he pushed me down on to the pink carpet on the floor.

Then there was a different kind of panic. He must have weighed 185lbs (84kg). I'm much lighter at 105lbs (48kg).

He held my arms over my head with just one of his and was trying to get my dress off. I was afraid I wouldn't be able to get out from underneath him, and still I never thought about being raped.

In 1990, rape was still stranger rape. It was not about people you liked or you were dating. People said you could be raped by someone off the street, they said, "Park where it's well lit, don't walk alone." I knew all those things. My dad gave me pepper spray when I went to college. I didn't wear it around my neck on a date, though.

I think no-one ever told this guy, "No". I think he had a ginormous ego, and had always had what he wanted in life.

Find out more

Katie Koestner spoke to the BBC World Service Witness programme

Listen via the BBC iPlayer or download the podcast

What was even worse was that he was so adroit at getting what he wanted. He almost didn't hear me. I tried to be nice. I wasn't trying to kick him where it counted, or throw him out of my room. I just didn't want him to go so fast.

I tried to get him off me unsuccessfully, trying not to hurt his feelings. I kept saying "No," and "Please get off." And he kept saying, "Calm down, everything's going to be fine," and that was the moment when I lost my virginity against my will.

To have that special moment which I was saving for my wedding night squashed into a pink carpet on a cement floor in my room was jarring to my whole self, my whole soul.

The moment he left I didn't move. I felt paralysed.

The next day I went to the health centre. They sent me home with a bottle of sleeping pills. I went to the dean's office and he said, "You could ruin his life and you seem emotionally distraught, so you should go home and think carefully about this."

Then the guy started sending notes and leaving voicemails saying, "Don't try to avoid me, I'll find you and speak to you, you cannot escape me, I am in love with you."

I finally broke down and told my parents. I said, "Dad, I was raped."

He said, "I'll drive down and get him," then asked where it happened. I think he envisaged a parking lot and I said, "It happened in my room." Dad said, "How did he get in, did he bust your locks?" And I said, "No, he's another student, and I invited him to hang out with me."

My dad said matter-of-factly, "It would not have happened if you had not let him in your room, Katie," and then hung up the phone. So I was on my own.

My friends and his friends arranged a meeting with my attacker to talk it through. Our friends were hoping that if we could patch things up, we could all be buddies again.

I met him in his building, in the lounge. I said: "Did you hear me say 'No'?"

He said: "I heard your father is angry that you're not a virgin any more. I'll call him and tell him I'm a nice guy, and you're in excellent hands." And I said that wasn't the problem.

Then he said, "You were a little stiff the first time round, and we need some more practice and then you'll enjoy yourself a lot better." Then he said - and I remember this bit particularly - "It's always tough for the virgins." And that last comment was the one that snapped me.

At the end of that meeting, I had two choices. If I left the building and turned left, it would lead me back to my residence hall. If I turned right, it would take me to the police station.

Katie Koestner campaigns against sexual violence through her Take Back the Night charity

I felt my heart pounding. I was so afraid of what right versus left meant. Left was to be a good girl that everyone likes, not defy my parents, forget it all.

Instead, I went right. I told myself, "You must at least try to help save the next 19 girls that go out with him, who will feel exactly how you feel now."

It was incredibly embarrassing at the campus police station. There were all sorts of questions about sex and what I was wearing.

I felt like a jerk for having him over to my room and when I admitted I let him pay for dinner, I felt that was one more thing I had done wrong.

They questioned him and our friends. They noted bruising and tearing and the fact I was no longer a virgin. I hadn't screamed but I had bitten a hole in my cheek.

In the end the District Attorney decided that we only had a 15% chance of winning the case as back then "forcible rape" meant I would have had to fight him off.

The last option open to me was to use the university disciplinary system. There was a handbook of policies that all students agreed to on enrolment. In 1990 it just said, "You're not allowed to sexually assault someone."

So they held the first ever sexual misconduct hearing at this, the second oldest college in the country.

The hearing took seven hours and finished at 2am. My accused brought two legal aides with him.

My attacker admitted I told him "No" more than a dozen times. He said, "Eventually she stopped saying 'No' and I knew I'd changed her mind."

The next day the dean called me to his office and told me I should feel safe. They'd found him responsible and he wasn't going to be allowed in my residence hall for the remainder of the semester.

But he said, "You two make such a nice couple and he really likes you, so maybe you could get back together."

I was so furious I thought I'd write a letter to all the parents of the students at my college telling them what happened, saying, "If you care about your children, you need to protest."

I had no money for postage so I sent the letter to the local newspaper. I convinced them to use my full name, as I felt people needed to know I was real.

Then the Associated Press picked it up and it caught on like wildfire.

I had calls from dozens of newspapers and talk shows. I hadn't intended for this to happen but they convince you to speak to them by saying, "We have his side of the story, don't you want to defend yourself?"

So being a white, upper-middle-class, Christian, straight-A student, I had the right resume at that moment in history for the discussion which went: "Can a woman be attracted to a man, he buys dinner and they go home, does she still have the right to say 'No?'"

Katie Koestner at her high school graduation in 1990

Time magazine even put me on their front cover the week that Rajiv Gandhi died.

Meanwhile I trained as a rape counsellor. I found there was one location on campus where lots of rapes were reported, so I set up a one-woman protest and handed out flyers saying, "Do you want to go in, when three women were raped here last weekend?"

No-one wanted to hear it, though. When news spread that HBO were making a film about my experience, 2,000 students signed a petition saying I lied. It was getting more and more difficult to walk around campus.

It was especially shocking coming from women. People would say, "You're devaluing my degree, people will only know our college for rape." And I'd say, "Rape happens everywhere, it's the whole system that's flawed."

On talk shows I was always asked why I didn't try to fight him off, why I couldn't do something better. It was never, "Why did he presume that he could have sex with you?"

I was accused of doing a disservice to women, making us appear weak.

The presumption was men who committed rape could never be well-educated, affluent or talented at sports.

While I was still in college, I started going to high schools and telling young people about what happened to me to try to save them from going through what I had. Then I just felt like I couldn't stop and I've kept going these past 25 years.

You should see their tears. They hug you, they write notes, they tell their secrets and that is all worth it. Every time I make myself tell my story, there are 10, 20, 30 more stories that are told.

I tell young people that they are the generation that can change the conversation. It must be, "I am never too important to ask for someone else's consent," and, "I must always expect respect from everyone I am with," so expect respect and ask for consent.

In my case people called it "date rape" because I'd gone out to dinner. People stuck a descriptor in front of "rape", like there's "date rape" and "real rape".

That shocked me - that somehow if you got dinner out of it, then it wasn't a bad rape. "At least you had a nice meal."

I'm not going to say which is worse, being grabbed by a stranger off the road and you're lucky if you live, or being out with someone you think you can trust, who has all the makings of your Prince Charming and having them disrespect you completely.

If I had been raped on a street, then I'd have been afraid of strangers, but if you're raped by someone you know, then you're afraid of everyone.

For me the attack was just wrong. I didn't rate it, define it or judge it. I just thought that was wrong. No-one should ever go through what I did.

Katie Koestner was talking to Claire Bowes

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.