Is it possible to eradicate all diseases?

- Published

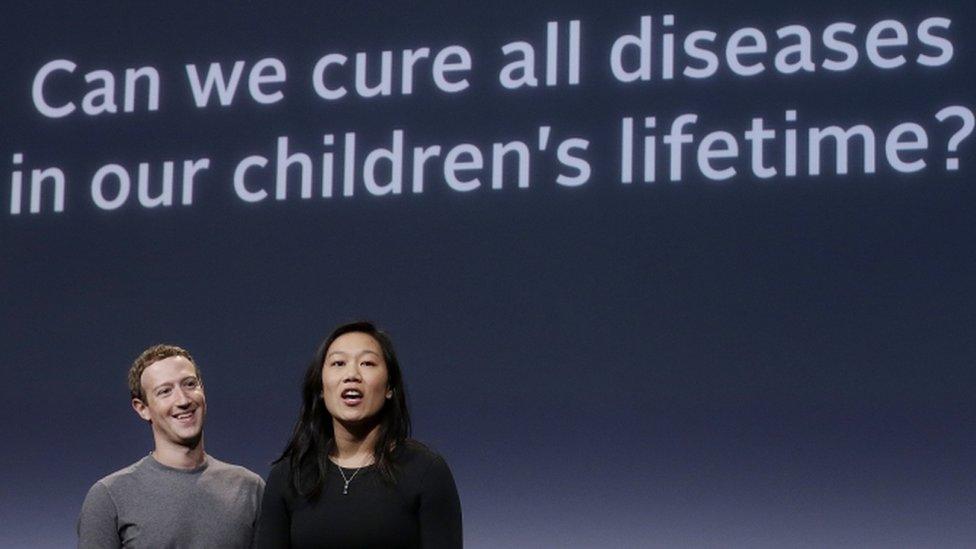

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife want to tackle all diseases by the end of the century. Just how feasible is this aim?

Pledging $3bn (£2.3bn) to fund medical research over the next decade, Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan said their ultimate goal was to "cure, prevent or manage all diseases by the end of the century".

By any reckoning, it's a hugely ambitious goal. At the event in San Francisco, the couple admitted it might sound crazy, but pointed out how far science and medicine had come in the last century, after millennia with little progress.

Zuckerberg said they had spent two years talking to experts to formulate and plan and this wasn't "something where we just read a book".

He acknowledged it would take years before the fund led to any new medical treatments and even longer before they could be used to treat patients.

But how realistic is the target?

"I don't think it's realistic," says Dr Sheena Cruickshank, lecturer in immunology at the University of Manchester, although she adds that it's "brilliant" that the couple want to invest in medical research.

The problem with treating diseases, she says, is that it's not "a static field".

"Everything changes. Our immune systems change, diseases often change," she says.

Not only do diseases mutate and become resistant to drugs, but environmental factors like climate change can alter the way infections spread.

Bill Gates has backed efforts to eliminate diseases including polio and malaria

"Some of the infections are challenging to deal with because we don't understand fully how the mechanism of infection works," she says. There are large gaps in human knowledge. No-one quite knows why some people will become ill if exposed to some strains of the common cold while others won't, for instance.

Some non-infectious diseases like cardiovascular disease and type-2 diabetes can be caused by lifestyle, and a "cure" might involve wholesale changes to people's behaviour, she points out.

There's also the sheer scale of investment required. Since 1971 the US National Cancer Institute alone has spent more than $90bn trying to find a cure. President Obama's 2017 budget includes $34bn for HIV efforts, external. More than $1bn, external was spent on Ebola research in 2014. Malaria funding has increased tenfold in the past decade, according to, external the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation - but as with all these other conditions, no cure has been forthcoming.

In this context, the figure of $3bn over a decade begins to look more modest.

"This is a lot but it's not anything like enough to beat diseases by the end of the century," says Prof Catherina Pharoah, co-director of the Centre for Charitable Giving and Philanthropy at Cass Business School in London. She points out that total UK spending on research around health amounts to around £8.5bn a year.

The only infectious disease of humans to have been declared eradicated, external by the World Heath Assembly is smallpox, the last known case having occurred in Somalia in 1977, though the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation aims to rid the world of polio, external and malaria, external. This week Microsoft also said it would, external "solve" cancer within 10 years by cracking the code of cells.

But while the International Taskforce for Disease Eradication has a seven diseases, external - including measles, mumps and rubella - on its hit list, it considers a further seven - including amebiasis (or amoebiasis) and buruli ulcer - to be ineradicable.

Prof Louis Niessen, health economist at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, is also sceptical that disease can be eliminated altogether.

"It's the old saying," he says. "You have to die of something."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external