The 'Walter Mittys': Why do some people pose as heroes?

- Published

Impostors who wear military medals they have not earned could face jail if a bill now before parliament is passed. What drives these "Walter Mittys" to invent fake tales of heroism?

Maybe it starts down the pub. There's talk of the SAS, and you've read all the books. An exaggeration becomes an embellishment, and then a lie.

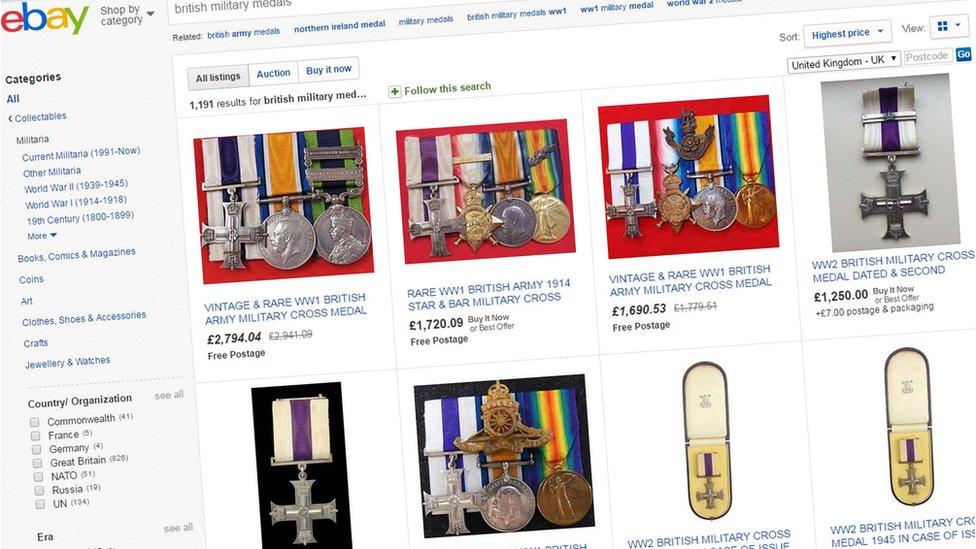

People are impressed. You get carried away. Buy medals on eBay. Wear them to a Remembrance Day parade.

Then you slip up. You get a detail wrong and someone notices. You're exposed as a fraud. A Walter Mitty.

In military circles, the name of James Thurber's fictional fantasist is applied to the persistent band of hoaxers who, for whatever reason, boast of military records they haven't earned. Sometimes Walter Mitty is abbreviated to Walter, or just Walt.

One well-publicised case involved Roger Day, who admitted, external he hadn't earned the 17 medals - including awards for serving in World War II, the Military Medal and SAS badges - that he wore at a 2009 parade in Warwickshire.

Roger Day (highlighted) was exposed at a Remembrance Day march

In 2008, bus driver Jamie Barrett was spotted marching in Edinburgh with members of the Parachute Regiment who had served in the Falklands. He had bought his medals online. After he was exposed, Barrett said, external: "I'm basically a Walter Mitty type of person."

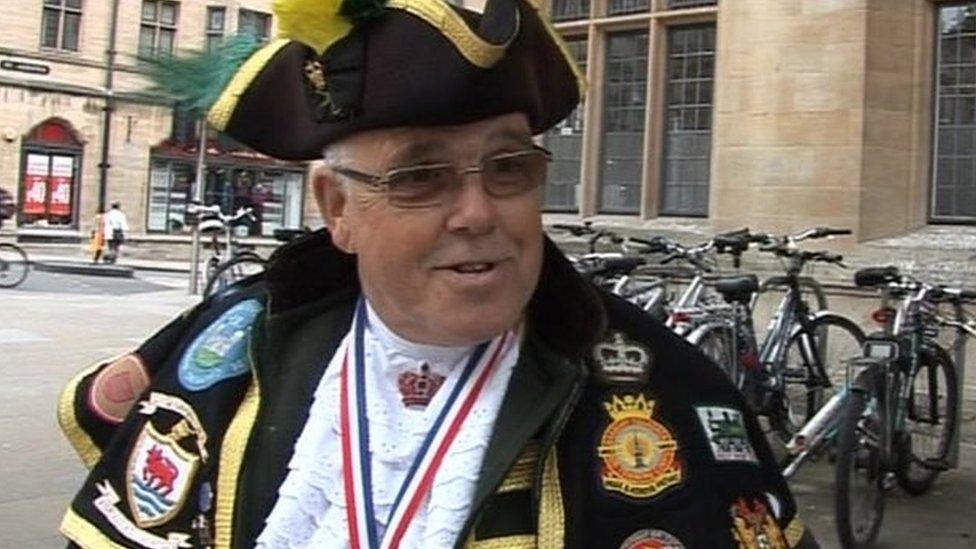

And last year, Oxford's town crier Anthony Church confessed to inventing a career in the armed forces. He had previously claimed he was a "regimental sergeant major" and had worn a Falklands medal.

Anthony Church resigned as town crier after he was exposed

Most people would regard the concoction of fake tales of heroism as reprehensible.

"It completely undermines genuine heroes," says Gareth Johnson, the MP for Dartford who introduced the proposed law - the Awards for Valour (Protection) Bill - that would make wearing unauthorised medals a criminal offence, punishable by prison or a £5,000 fine.

"People who have served their country in genuinely dangerous environments, then someone comes along and pretends that they are their equal - that causes a lot of offence," he says. "When people see veterans it's important that people have confidence their medals are legitimate."

Internet vigilante groups with names like the Walter Mitty Hunters Club are dedicated to uncovering and shaming them, and these exposes are regularly picked up and given extra publicity by an indignant tabloid press.

But what actually motivates the Walter Mittys to concoct their often elaborate tales is not always obvious.

In Day's case, a court was told he had started to make up stories to impress his new wife, who was 24 years his junior.

Confronted after his exposure, Barrett's explanation for his behaviour was more prosaic: "I had been collecting the medals and silliness got hold of me. I got a bit carried away, put the medals on and went. I didn't realise that it would upset other people."

One of the more spectacular cases of recent times involved Capt Sir Alan McIlwraith, CBE, DSO, MC, MiD - or, rather, plain Alan McIlwraith, a call-centre worker living on a Glasgow council estate who built up an elaborate fake persona as a highly decorated officer who had finished top of his class at Sandhurst and served in the Balkans.

"The lie had just gone too deep, it's like a weed that invades your life. Once it's taken root, there's nothing you can do about it," McIlwraith, who was exposed as a fraud in 2006, told the Guardian, external.

Some will have had no involvement with the armed forces whatsoever, Greenberg says. But others might embellish their own military service into something more impressive-sounding.

Richard Lee claimed he had served with the Royal Marines' mountain troops when he set up the worldwide endurance competition, Spartan Race. In fact, it turned out, external he had enrolled in the Officer Training Corps but dropped out before qualifying.

Just how many Walter Mittys there are isn't entirely clear.

In evidence to the Commons Defence Committee, external, the Royal British Legion (RBL) said it in its experience "instances of so-called 'Walter Mittys' appear to be rare" while the The Royal Air Force Families Federation said the issue was "not widespread".

However, 64% of 1,111 Naval Families Federation members surveyed over four days said they had personally encountered individuals wearing medals or insignia that had been awarded to someone else. Gareth Johnson says his own RBL branch has had to expel two members who concocted bogus military records.

Neil Greenberg, professor of defence mental health at King's College London, also argues that the phenomenon is more widespread than you might expect.

"I've seen more people who say they were at the Iranian embassy siege, external than were actually at the Iranian embassy siege," he says.

Gareth Johnson says the UK is highly unusual in not already having legislation of the kind he proposes. The wearing of medals without authorisation was made illegal by Winston Churchill after World War One - but in 2006, when the new Armed Forces Act came into effect, this was effectively repealed.

So although Roger Day pleaded guilty to falsely wearing medals in 2010, a community order imposed on him was scrapped after his lawyer noticed that this had stopped being an offence, external 11 days before the parade.

Under the Fraud Act, anyone who uses medals for financial gain can be prosecuted - but if no such benefit can be proved, no offence has been committed. One man who did gain financially is Christopher Griffin, a bodyguard who falsely claimed to have been a British Army Captain for 11 years, who admitted, external two counts of fraud by false representation at Plymouth Magistrates Court last year.

Neil Greenberg, who has assessed several military impostors, isn't convinced that stricter legislation will deter them.

"It's often not fully conscious," he says. They are typically fairly pathetic individuals, as he puts it, who are "doing it to bolster their own self-esteem".

"Their problems are greater than that they say they were in the SAS," he says. Many will have an "abnormal or end-of-normal personality", while a few will have serious mental health problems.

Critics have warned that the bill before Parliament would end up targeting people who were mentally ill. Johnson says it would be up to the Crown Prosecution Service to decide whether it was in the public interest to prosecute any individual accused of wearing medals they hadn't earned.

He also says that people who wear medals won by relatives, to honour their memory, would not face prosecution.

Walter Mitty

In James Thurber's short story, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, the mild-mannered hero imagines himself as a fighter pilot, an assassin and a brilliant surgeon

It was first published in the New Yorker in 1939 and adapted for the screen twice - first in 1947, with Danny Kaye in the title role, and again in 2013, starring Ben Stiller

The name "Walter Mitty" entered the lexicon, with Oxford Dictionaries defining it as "a person who fantasises about a life much more exciting and glamorous than their own"

Johnson's proposed law has won the backing of ministers. "I fully support this bill," Defence Secretary Michael Fallon says. "Medals recognise our forces who risk their lives for our freedom. It's important their service is properly protected."

The Commons Defence Committee also backs the legislation. In its report on the proposed law, it concluded there is "a tangible and identifiable harm created by military impostors". Its chairman, Julian Lewis, said such "contemptible fantasists" need to be deterred.

Even without the threat of prosecution, being unmasked as a Walter Mitty in the media or online can be devastating in its own right. The BBC contacted a number of men who had been unmasked as impostors. None was prepared to speak on the record, but several spoke of their deep shame and said they had contemplated suicide.

Many will have no sympathy. But Greenberg says everyone should examine their own capacity for Walt-like behaviour.

"Most people exaggerate," he says. "There's an element of this in all of us."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.