100 Women 2016: Researching the female orgasm

- Published

Dr Cindy Meston, one of the BBC's 100 Women, explains the sympathetic nervous system

You may be used to hearing about the female orgasm from women's magazines rather than scientists, but researchers are slowly beginning to study it - and often contradicting the advice columns. Part of the problem, they say, is that the female body has been studied far less than the male body and is far less well understood.

"I call it the ring of fire. It felt like fire in a circle in between my legs and that was a constant feeling - it was burn-y itchy, and then with intercourse or even a tampon it was like a serrated knife, very painful."

Callista Wilson, a San Francisco fashion stylist, first experienced this when trying to use a tampon at the age of 12. She was in her 20s before she finally saw a doctor.

"She seemed extremely puzzled that anything would be wrong," Callista says. "She said: 'You look perfectly normal so I would suggest you go to a therapist to talk about whatever's causing you this pain, it must be in your head.'"

Callista Wilson consulted 20 doctors before her problem was solved

And it was another 10 years before Callista got a proper diagnosis.

Her sexual problems during this period affected every aspect of her life, she says, leading to depression and the breakdown of her relationship. Finally, after seeing 20 doctors, she found herself in the waiting room of Dr Andrew Goldstein, director of the Center for Vulvovaginal Disorders in Washington DC.

He told her that she had been born with 30 times the normal amount of nerve endings in the opening of her vagina - which meant that when her vagina was touched, it felt as though it was being burned. The solution was to have a circle of skin at the opening of her vagina removed. Once that was done, she was able to experience pain-free sex for the first time.

What is 100 women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. We create documentaries, features and interviews about their lives, giving more space for stories that put women at the centre.

Other stories you might like:

'I married a man to keep my girlfriend'

'Adults are so obsessed with children they have no time for important things'

Callista's problem, known as congenital neuroproliferative vestibulodynia, is not common. But one thing researchers have recently come to understand is that the pelvic nerve system varies enormously from one woman to the next.

When New York gynaecologist Dr Deborah Coady began to look into the subject she found the nerves in the male genital region were fully mapped, but there was no information about women. So she teamed up with specialist surgeons and did the work herself, with interesting results.

"We've learned that there's probably no two of us that are alike when it comes to the branching of the pudendal nerve," Coady says.

"The way the branches [of the nerve] move through the body leads to difference in sexuality, meaning what areas may be more sensitive for one woman may not be for another."

The pudendal nerve is the most important nerve for making orgasms happen - it's the one that links the genitals to the brain-firing messages of touch, pressure and sexual activity.

Coady also found that each woman has a different number of nerve endings at each of the five erogenous zones in the genital area - the clitoris, the vaginal opening, the cervix, the anus and the perineum.

"This leads to why some women may be more sensitive in the clitoral area, some may be more sensitive just in the vaginal opening," she says.

Find out more

Listen to Why Factor: The Female Orgasm on the BBC World Service on Friday 2 December

Click here for transmission times, or to listen online (from 19:30 GMT)

And it is one reason why generic sex advice in women's magazines is often unhelpful.

"Fifty per cent may respond the way the magazine says," Coady points out. "But then there's going to be another bunch that - due to their anatomy, and due to the fact that nerves vary in all of us - may not respond like the magazine says."

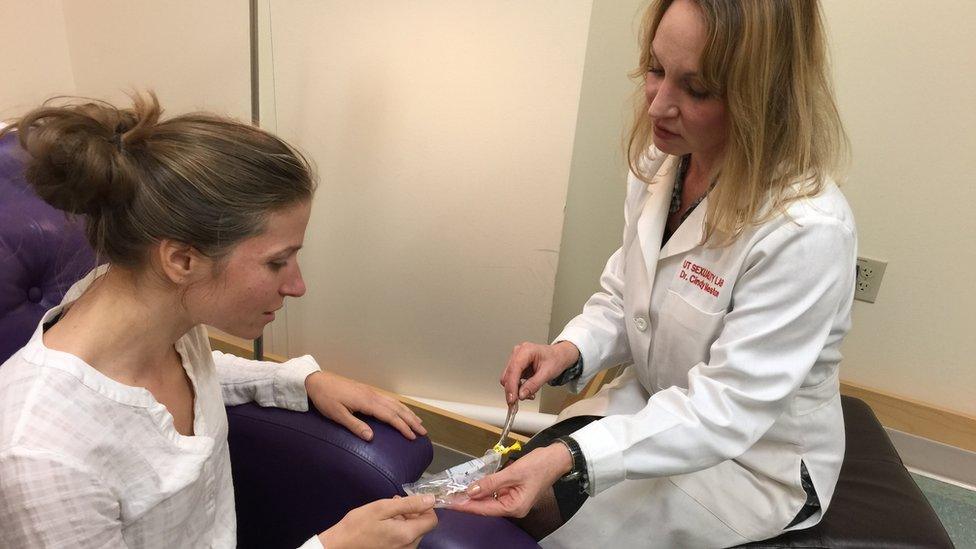

Another big myth has been exposed at Dr Cindy Meston's sexual psychophysiology lab at the University of Texas at Austin.

When you think of a lab, you might think of lots of white, hard surfaces, bright lights and microscopes, but this one is quite different. People who take part in Meston's studies sit on a purple leather reclining sofa opposite a widescreen TV and watch videos of people having sex.

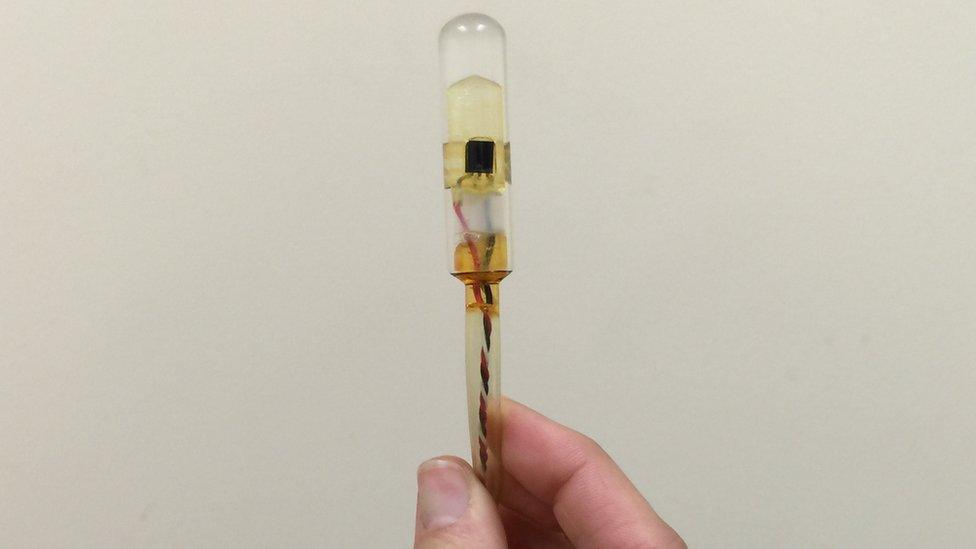

From the next room, Meston monitors their heart rate and the blood flow to their genitals, using a vaginal photoplethysmograph. Two inches long and about the size and shape of a tampon, it is inserted into the vagina. When switched on it emits a light, and by measuring how much light is reflected back, the scientists are able to tell how much blood is flowing into the vaginal tissue - and therefore how physically aroused the woman is.

Dr Meston (r) explains how to use the vaginal photoplethysmograph

The results of Meston's studies go against perceived wisdom.

"For years we were told, 'Have a bubble bath, calm down, listen to relaxing music, do deep breathing exercises, chill out before sex,'" she says.

"But my research shows the opposite, that you actually want to get women in an active state.

"So, you can run around the block with your partner and get them to chase you around the block, or watch a scary movie together, ride a rollercoaster together, even a good comedy act. If you really get laughing, you're going to have a sympathetic activation response."

Meston is talking about the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for subconscious muscle contractions that get us ready for the flight or fight mode, like heart rate and blood pressure. She has found that if this system is activated before sex it will help women respond more intensely and more quickly.

It's quite the opposite for men.

For years it was assumed women worked in the same way as men but Meston's work has shown this to be a mistake.

Andrew Goldstein has also been aware since his student days that the female body and female sexuality is poorly understood.

"I completed a residency in obstetrics and gynaecology that was 20,000 hours," he says. "I had one 45-minute lecture on female sexual function and I can tell you what was said during that 45 minutes was almost all completely wrong,"

He adds: "Any sexual problem in women is given less importance than any sexual dysfunction in men. I think that there's clearly a double standard. Unfortunately it's obvious if men have sexual dysfunction, if they have erectile problems, you can see that, [whereas] women are stigmatised if they have any dysfunction. They are told it's in their head."

Meston says that it is hard to get funding for research into female sexual pleasure - the female orgasm is not seen as a "significant enough social problem", she argues. She also detects in the medical establishment a puritanical disapproval of this area of study.

"There are a lot of conservative reviewers who don't want to see federal funds going into sex research and so as a sex researcher you have to be a little bit creative," she says. "I was told straight-out to take 'sex' out of my proposal. They told me: 'You can talk about well-being or marital satisfaction, but talking about sexual arousal or orgasm as an ultimate end point will diminish your chances of getting funded.'"

On one occasion she was invited to speak to a group of retired academics, but was "un-invited" when the subject, Women's Sexuality, was advertised.

"There was such resistance and horror that we'd be talking about female sexual pleasure," she says. "I was horrified and offended. It depressed me to tell you the truth. I thought we were at least beyond that."

How does Callista Wilson feel when she hears about the difficulty of carrying out the kind of research that brought to an end her years of pain?

"Everyone's born out of a vagina, why don't we know more about them?" she says.

"Why don't we care more about them? Why aren't we more invested in them? This would benefit men and women to have more research and funding and more conversations about this. It would only benefit everyone."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external