The US Air Force's commuter drone warriors

- Published

Drone pilot Lt Col Matt Martin says his role is "surreal"

In the past, soldiers went off to war and left their families behind. But drone pilots commute to work - and to war - each day. Vin Ray was given rare access to the only US Air Force base devoted entirely to flying drones, where he discovered the pilots' strange double life.

If you're a drone pilot, there's a strong possibility you live in Las Vegas. And your commute to work is against the traffic.

We were told to drive northwest out of the city on US Route 95. The road stretches out through the barren, inhospitable scrub of the Nevada desert.

Pay attention, we were told, because the signpost is small. In fact, it's very small. But we eventually arrived at our destination: Creech US Air Force Base, a small, flat, city in the desert. And the only air base devoted to flying drones.

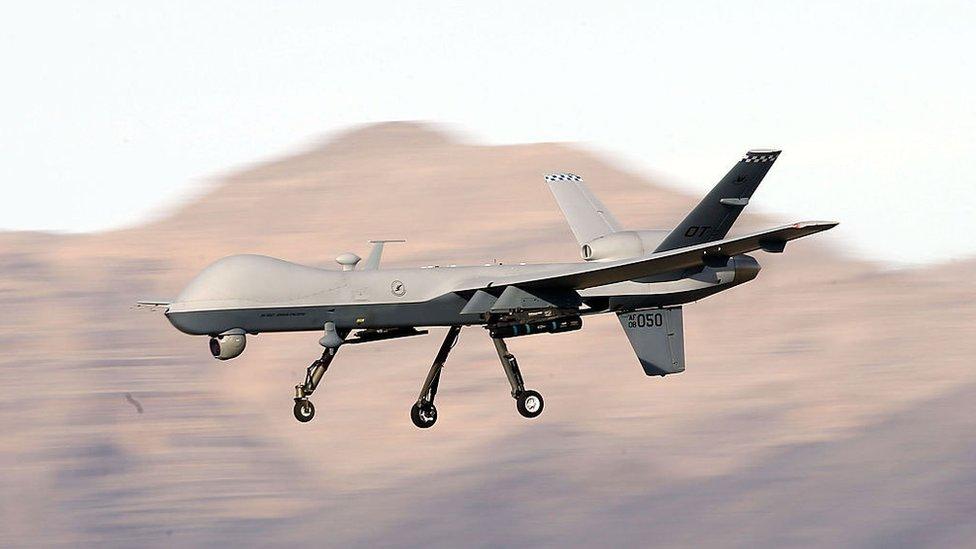

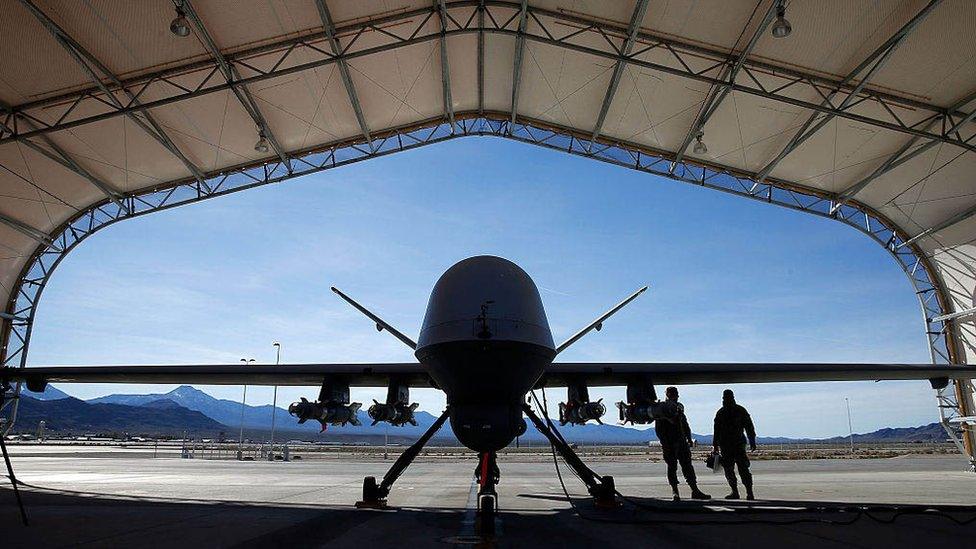

Inside the base, comparisons with science fiction are hard to avoid. A drone looks like a conflation of a giant insect and a light aircraft. It's unmanned.

Standing by a runway, we watch a drone land and pass right in front of us.

The camera underneath its chin, swivels quickly sideways and looks right at us - someone, somewhere on the base, is watching us.

I'm escorted through a non-descript door in the side of what looks like a beige metal shipping container. It's cramped inside. At the far end there's a pilot seated on the left, who flies the drone and fires the missiles.

The sensor operator sits on the right - they operate the camera and fix the laser on the target for the missile to hit. They're focused on a bank of screens, switches and buttons. This is today's kind of cockpit. But it doesn't feel like a battleground.

For a start, there's a sensory deficiency. From my experience on the ground, you can taste war - you can smell it and you can certainly hear it. In here there's a just a mute video.

But that's not the only difference.

Traditionally, soldiers in a war zone are based together. They have each others' camaraderie, and they're separated from their families.

But it's not the same if you're commuting to work every day.

Obviously, the drive itself is simple. But the psychological journey is altogether different. Imagine. Between six in the evening and six in the morning you might collect your kids from school, pick up some groceries on the way home and help make dinner.

But between 6am and 6pm you have a licence to kill.

Find out more

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service or on Radio 4 on Thursdays at 11:00 BST and Saturdays at 11:30 BST

Remote Control War, in which Vin Ray examines how drones are changing the face of warfare, goes out on BBC World Service's The Documentary on Tuesday 10 January - click here for transmission times, or listen on iPlayer

This commute is familiar to Lt Col Matt Martin. He's a hugely experienced former drone pilot. He exudes a quiet strength and a ready charm.

But he talks about his schizophrenic existence, his inability to have a normal life and the strain it took on his family.

"It's a surreal enterprise," he says. "You only have the drive to work and then you're flying. So for me, I would take that drive to switch gears. I would step into my cockpit and be totally immersed in flying the drone. Then a few hours later I would step out and be back in Las Vegas, in a totally different time zone, different time of day."

Here's what the base commander Col Case Cunningham told me: "When they walk through the gate, they're in a war. Although physically they are at home, mentally they're at war. So in effect we're asking them to redeploy every single day, to go back home and be parents and be loved ones - and then come back to war again".

Such are the new frontiers of the modern battlefield.

These drone pilots can sit in Nevada and watch a potential target 8,000 miles (12,000km) away for months on end, building up what they call "patterns of life" - building what's been called a "remote intimacy" with their prey - all in the knowledge that, one day, they may kill them.

A conventional fighter pilot will fire missiles and then head back to base. But drone pilots are required to circle for some hours afterwards, to assess the damage. The picture they're looking at is extraordinarily clear - and the damage is often in the form of body parts.

Small wonder that Creech now employs a psychologist for drone pilots suffering stress. Drones are globalising the battlefield, blurring the boundaries between war and home.

As we get ready to leave the base, the moon rises over the mountains and darkness falls quickly. There's a long traffic jam as some of the 3,500 air staff wait at the gates to leave the base - a snake of red tail lights heading back to Vegas and the warmth of their families.

And when they get home? Well, friction can stem from one simple question: "How was your day?"

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.