Jasvinder Sanghera: I ran away to escape a forced marriage

- Published

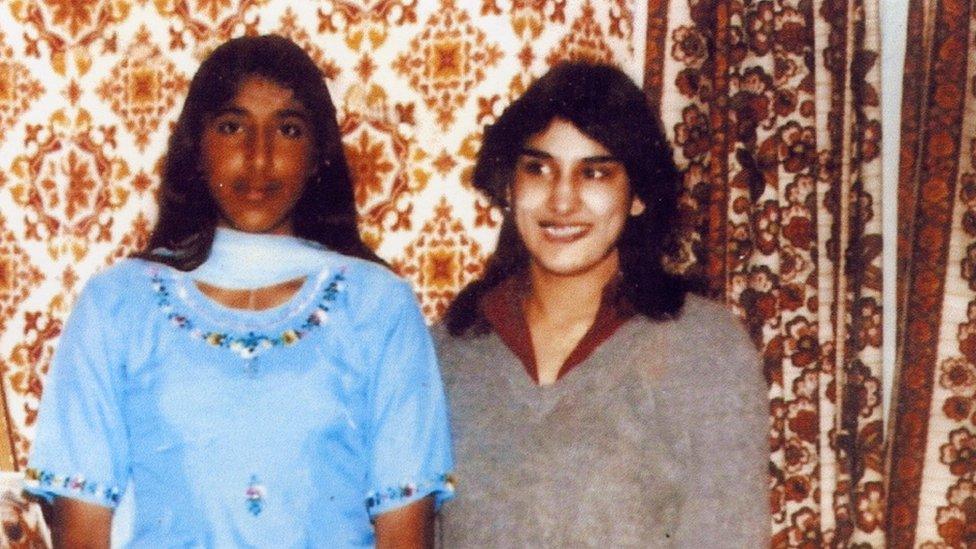

Jasvinder (R) aged 15, with her sister Robina

Jasvinder Sanghera was locked in a room by her parents when she was 16, when she refused to marry the man they had chosen for her. Here she describes how she escaped with the help of a secret boyfriend - but lost all contact with her family as a result.

Growing up we had no freedom whatsoever. Everything was watched, monitored and controlled. We understood that we had to be careful how we behaved so as not to shame the family.

I'm one of seven sisters and there's only one younger than me so I'd watched my sisters having to be married at very young ages - as young as 15.

They would disappear to become a wife and go to India, come back, not go back to school and then go into these marriages and be physically and psychologically abused. And my impression of marriage was that this is what happens to you - you get married, you get beaten up, and then you're told to stay there.

My parents were Sikh and Sikhism was born on the foundation of compassion and equality of men and women, and yet here we have women who were treated very differently. My brother was allowed total freedom of expression. He was also allowed to choose who he wanted to marry. But the women were treated differently and that was reinforced within the communities. It's gone unchallenged and it's deeply ingrained.

I don't think I was smarter. I just don't know what it was within me. My mother used to say: "You were born upside down, you were different from birth."

Maybe she helped me out by saying that, because it made me question a number of things, and then when I was shown the photograph of this man, as a 14-year-old, knowing that I'd been promised to him from the age of eight and being expected to contemplate marriage, I looked at this picture thinking: "Well he's shorter than me and he's very much older than me and I don't want this."

And it was as simple as that.

But within our family dynamic we were taught to be silent.

Saying no to the marriage meant my family took me out of education and they held me a prisoner in my own home.

I was 15 and I was locked in this room and literally I was not allowed to leave the room until I agreed to the marriage. It was padlocked on the outside and I had to knock on the door to go the toilet and they brought food to the door.

My mother was the very person who enforced the rules. People don't think of women as the gatekeepers to an honour system.

So in the end I said yes, purely to plan my escape. And it was as simple as that, because then I had freedom of movement.

The only friends we were allowed had to be from an Indian community as well. And my best friend, who was Indian, it was her brother who helped me in the end.

He became my secret boyfriend. He saved some money and said, "I want to be with you and I'll help you to escape." He would come to the house at night and stand in the garden and we would secretly mouth things to each other through the window.

One day he dressed up as a woman and went into a shoe shop and pretended he was shopping. He handed me a note which said, "I'll be at the back of the house at this time - look out of the window." So I did, and he mouthed for me to pack my wardrobe and I lowered two cases down using sheets tied together, and flushed the toilets so my mother wouldn't hear.

And then one day I was at home with my dad, who was at home because he worked nights, and the front door was open, and I just ran out.

I ran all the way, a good three-and-a-half miles, to where my boyfriend worked and hid behind a wall and waited for him to come out. He went and got my cases and then picked me up in his Ford Escort and got me to close my eyes and put my finger on a map, and it landed on Newcastle.

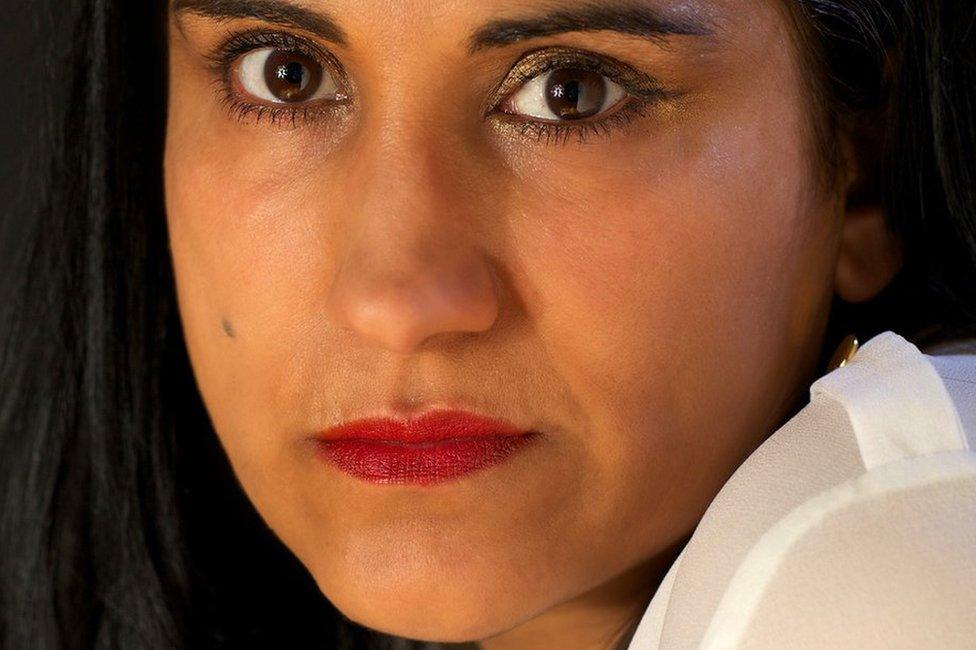

Jasvinder, now 51, helps others who are in the same situation as she was

I sat in the footwell of the car all the way so no-one would see me and then when I saw the Tyne bridge I was absolutely amazed by it because I had never been anywhere outside Derby.

My parents reported me missing to the police and it was the police officer who told me I had to ring home to let them know I was safe and well.

My mother answered the phone and I said: "Mom, it's me. You know, I want to come home but I don't want to marry that stranger."

Her response has stayed with me for the rest of my life. She said: "You either come back and marry who we say, or from this day forward you are now dead in our eyes."

It was only later on when things settled down that I begin to think, "I've done it but where's my family? I want my family." I was missing them terribly. You feel like a dead person walking.

My boyfriend used to drive me to my hometown at 3am just so I could see my dad walking home from the foundry.

What changed how I felt was the death of my sister, Robina. She was taken out of school at 15 for nine months, married to a man in India, and then came back and put in the same year as me and nobody questioned this at all. But he treated her terribly and when her son was around six months old she severed the relationship.

She then married for love and my parents agreed to it because he was Indian - Sikh and from the same caste as us. She again suffered domestic abuse but my parents made it clear that because she had chosen him she had a duty, doubly, to make it work.

She went to see a local community leader - they have a lot of power, my parents would have seen his word as the word of God - and he told her: "You need to think of your husband's temper like a pan of milk - when it boils it rises to the top and a woman's role is to blow it to cool it down."

When she was 25 she set herself on fire and she died. When she was - I say - driven to commit suicide, that was the turning point for me.

What is 100 women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. We create documentaries, features and interviews about their lives, giving more space for stories that put women at the centre.

Other stories you might like:

Trolled for giving sex advice to strangers

I've learned to live my life with no expectations of family whatsoever. I've never had a birthday card in 35 years and neither have my children. For my children it's a total blank on their mother's side when it comes to family. I've got nephews and nieces that I'll never meet because all of my siblings sided with my parents.

I have actually stipulated in my will that I do not want any of my estranged family to be at my funeral because I know the hypocrisy that exists within them. They will want to show their face, but if they couldn't show it when I was alive, I'm not going to give them that privilege when I'm gone.

I have three children - Natasha who's 31, Anna who's 22 and Jordan who's 19.

You almost live vicariously through your children because you want them to have everything you never had.

My daughter married an Asian man and I was worried - I didn't want this family to take it out on her that her mother was disowned and had run away from home. But thankfully for me my fears were completely unfounded because here was an Indian family that did the exact opposite of what my family did.

Starting a charity, Karma Nirvana, in 1993 from my kitchen table allowed me for the first time to start talking about my personal experiences and what had happened to my sister. My family wanted us to never speak about Robina again.

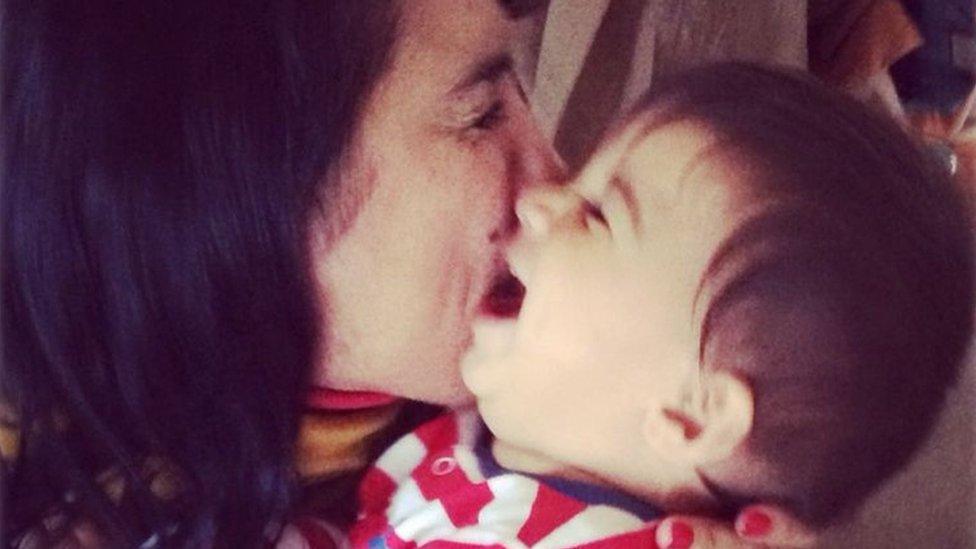

Jasvinder with her grandson

Sometimes at Christmas my children would meet these different women at the dinner table - survivors disowned by their family - and they had no idea who would be the next person at our table, but they understood why.

The charity will be 25 years old next year. We have helped make forced marriage a criminal offence, we have a helpline funded by the government which takes 750 calls a month - 58% of callers are victims and the others are professionals calling about a victim.

We do risk assessments, offer refuge and help plan escapes.

We still don't have enough responses from professionals and we've got to try to increase the reporting, but we're getting there. This is abuse, not part of culture where we make excuses - cultural acceptance does not mean accepting the unacceptable. Abuse is abuse.

I'm a grandmother now - my daughter's expecting her second child in March. And you know when I look at them I think to myself, 'they're never going to inherit that legacy of abuse because of that decision I made when I was 16.'

And that really makes me feel a lot stronger.

Jasvinder appeared on The Conversation, on the BBC World Service - listen to the programme here - and also spoke to Sarah Buckley for 100 Women.