Beaten up for being gay

- Published

Fifty years ago, gay sex between men in private was decriminalised in England and Wales. Despite this, hate crimes against gay people have persisted, and the number of attacks recorded by police has been rising. There were 7,194 in England and Wales in the year to April 2016. Campaigners say this isn't the full picture, though, as many victims still don't report assaults. Six people affected by hate crimes share their stories.

Warning: This story contains details of violence and images which some readers might find upsetting.

James and Dain were enjoying a night out together in Brighton in May 2016 when they were followed out of a nightclub and attacked on the seafront. The assault has left physical and emotional scars.

James: We were at the bar and we got this look from a couple of guys from across the dance floor. It takes a lot to make me feel uncomfortable but it was just such a weird look they gave us. Dain had his arm around me. I don't think they liked that. Then they started shouting at us. I told Dain we needed to get out of the club into a taxi the quickest way possible.

Dain: We left the bar. No-one was about. All of a sudden I heard running behind us. There was no way we were going to outrun them. They grabbed us from behind and chucked us to the floor. I was lying on the pavement and all I could see was James but the next thing I saw was a shoe coming towards my face. That knocked me completely unconscious.

James: One of the boys started kicking Dain's face really rapidly. There was a lot of aggression and shouting of "gay boys". Every time I tried to crawl closer to Dain, I was dragged along the pavement. At that point, a taxi drove past and called the police. I remember standing up for the first time and Dain looked at me and said, "I can't see."

Dain: My eye socket was completely shattered. I had haemorrhages in both my eyes and fractures on my cheeks. My tooth was chipped and my nose was broken as well. I remember being in hospital and kept asking, "Am I going to be able to see again?" They said, "We can't tell you because everything is so swollen." They couldn't even open my eyes.

Dain in hospital after the attack

James and I were very close anyway but spending that much time with each other really proved to me how strong our relationship is. I'm a very resilient person and I'm not going to live my life how someone else wants me to. I'm not going to let anyone change that. If anything, this has made me want to be who I am even more.

James: It's made him stronger and it's made him not care about what other people think and to go out there and be himself even more, whereas it's done the opposite to me. It's changed me. I've changed my thought process and mindset, how I think, how I look, how I speak, who I'm with, where we go and it's sad because I remember how we were before it happened and I look at us now and it's upsetting because it's them who made this happen. That's what's hard to accept.

It's a year since it happened and I thought things would probably get easier but they haven't. When we're out and about he wants us to look like we're together obviously but I'm scared of something similar happening again. It wasn't like that a year ago. We didn't go down the street holding hands but I wasn't fully aware of us making sure that we weren't seen as a couple.

I couldn't ever forgive the people who attacked us or forget what happened. It will stay with me and I'm sure it will stay with them for the rest of their lives.

Both attackers, Gage Vye-Parminter and Matthew Howes, pleaded guilty to grievous bodily harm and assault and were sentenced to seven years in prison.

Becky and Alex were attacked on a night out in Croydon in August 2016. One man was convicted but he left the country before he could be sentenced, leaving the couple feeling angry and frustrated.

Alex: I'm angry about everything that's happened - the fact that I had a black eye to explain to a six-year-old, why Mummy was hurt, why Becky had bruises. It's not something I want to explain to my child, that there's hatred in this world. It's odd that it still happens just because of who we choose to love. For once we had a babysitter and got out of the house and that happened. We haven't been out since.

Becky: The first thing he said was, "I like lesbians" and I thought "Oh God, not one of these."

Alex: He had a South African accent, all seemed quite pleasant and he seemed quite tipsy but I'm never really rude to anyone. He asked our friends to kiss, to which they said "No" and I said, "It's not for your pleasure."

Becky: He said something like "dyke" which offended one of my mates. You don't say that. We went to the kebab shop to get a bit of food. I didn't think it was going to get violent.

Alex: Another guy that had begun joining in then started circling us as a group and focused his attention on me.

Becky: That's when he started getting touchy-feely, groping Alex's breasts and really hanging on her arm. He called us "fat dykes" and she pushed him away. The other guy saw her do it. He swung for her.

Find out more

James, Dain, Becky, Alex and Jenny tell their stories in the TV programme Is it safe to be gay in the UK? Viewers in the UK can watch it at 21:00 on Tuesday 1 August on BBC One or catch up later online.

The documentary is part of Gay Britannia - a season of programming across the BBC to mark the 50th anniversary of The Sexual Offences Act 1967, which partially decriminalised gay sex between men in England and Wales.

Alex: I got groped, kicked and slammed into a street light. My wife got punched and our two friends got punched too. To hit a woman is wrong but do that just because we didn't want them is disgusting and vile. I am so angry I have been violated for loving my wife. The next day I had to wear glasses as I couldn't cover up the darkness around my eye.

I feel guilty because I have chosen to love Becky which in turn has brought this crap into my son's life. Just me and him, we look completely normal. We wouldn't attract attention but being with Becky does because she is so obviously gay.

I'm disappointed, upset and angry with my attacker, at the court, the justice system. I just hope and pray it doesn't happen to someone else.

A South African man, Sazi Tutani, was found guilty of assault but he couldn't be sentenced because he had left the UK and returned home. There is a warrant out for his arrest. Another man was found not guilty of all charges.

Ian Baynham died after being punched and kicked on a September night in 2009 in Trafalgar Square, central London. His sister Jenny, who is also gay, talks about the loss of her "inseparable link".

Ian was the first born in the family and he was four years older than I was. He had this amazing smile, he just loved life really. When things were tough, he'd be there and he'd never judge you.

As we grew up, we went our separate ways. In our early 20s, I went to a gay party with a girl. It was packed. I looked across the room and I thought: "That's Ian."

He spotted me. He came up to me, put his arm around me and he said, "What are you doing here?" and from that moment we realised we were both gay. That really forged this inseparable link.

On the night he was attacked, he was walking down the street with his friend, Philip. He'd just had his first week at work so he was going out to have a drink.

Someone shouted, "Faggots." My brother turned round and said, "I may be gay but…"

And then there was some kind of altercation. He was kicked in the groin and punched.

They were kicking him, stamping on him and shouting at him.

It's shocking, absolutely shocking. I couldn't believe it. There was a crowd of people around him, which you can see on the CCTV footage. How could you leave somebody in that state? Why didn't they go back to him and check he was OK? Those questions still nag at the back of my mind. To walk away, how could you do that?

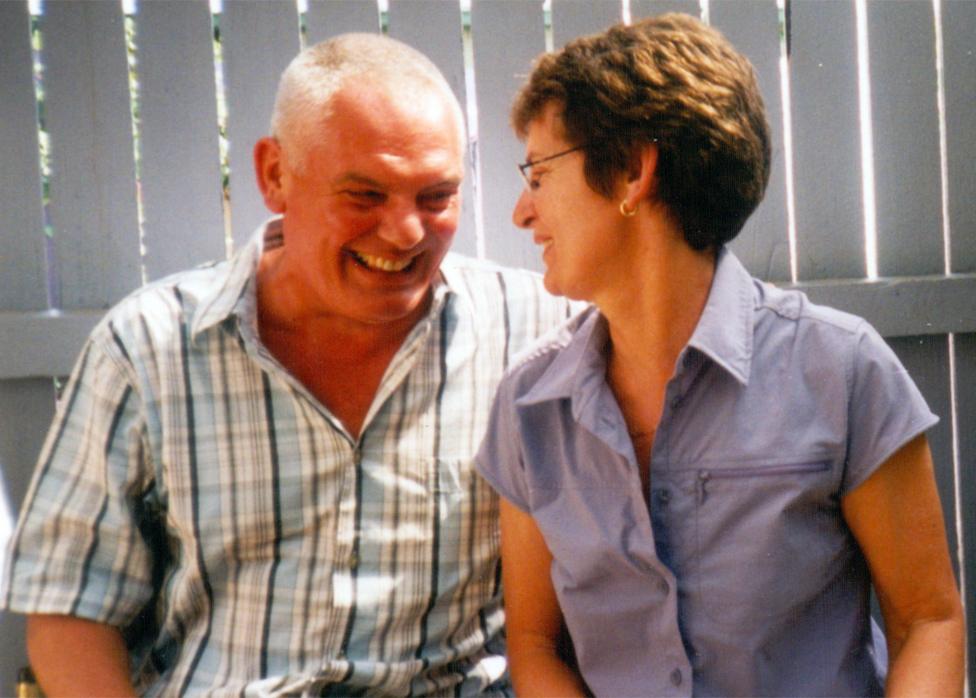

Ian and Jenny together

Ian was in hospital for 18 days. When I got there he was unconscious with two big black eyes. His breathing was changing. My experience told me that this was the final breath. He struggled a bit and then he stopped breathing. And so he died. We were with him. It was very sad.

Thousands of people with lights attended an extraordinary coming together of gay and straight people in Trafalgar Square because of what had happened. It was magic really and such a fitting event for Ian. Just across the road was where he was last conscious. I went there a couple of times to look. It really is significant. That tree, I know it very well. He's part of Trafalgar Square now.

We always used to say, "We can always live together when we get older and retire. We'll be like Darby and Joan and have a few tea parties." We'd laugh about it. I probably miss him more and more as I get older.

You can't have hate and I think hate is a very divisive thing to hold on to. I'm starting the restorative justice programme and hoping that will give me some sense of closure and also that it will help the offenders. I'd like to meet them all. They're still alive and they have a life. I do care what happens to people and I know some people don't have the same advantages as others. I actually think he would support me doing this and this really will be a bit like a springboard in helping me move on. I'm hopeful.

Ruby Thomas and Joel Alexander were found guilty of manslaughter. Thomas was sentenced to seven years in prison and Alexander was sentenced to six years.

Over the past 12 years, Paul Harfleet has planted hundreds of pansies across the world at spots where gay people have been subjected to homophobic abuse - including locations in Austria, Sweden, Turkey and the US.

It started in Manchester in 2005 when I experienced three separate instances of homophobia in one day. People were really shocked that I had these experiences all the time and I thought, "I have to do something about this."

I began to plant pansies wherever I'd experienced abuse. I wanted to do something that changed the location. I never wanted there to be any signage, it had to be something that was subtle but noticeable, in the way that I am in the street. A pansy is a pansy, you kind of understand and read what it's about just by knowing it's there.

Quite quickly, people started telling me where they had experienced abuse and I started planting for them too. If I plant a flower for someone who's been murdered I usually dedicate it to them. I take photographs and add them to my website, external.

Westminster Bridge, London

I often name the pansy after the abuse that has happened. The first one I planted was called: "I think it's about time we went gay bashing again." Two builders sitting on a wall said that directly to my face and I was so shocked I really didn't know what to do.

When you have that experience you're forced to think about what it is you can do. Do you react, do you close up?

The ritual of digging into the ground, kneeling on the ground, feels solemn and slightly healing. I'm subverting this terrible thing that's happened and turning it into something more positive. It also raises awareness.

Oxford Road, Manchester

When someone's been violently attacked, the location is so loaded that they can't stop thinking about it when they go past. What I witness when I go back with them is their experience and healing of that location. They can then think: "This isn't only the place where I was beaten up but also somewhere a pansy was planted." It's almost like sticking a plaster over the violence.

I plant pansies wherever I am. Unfortunately everywhere I go there's usually a place where someone has experienced homophobia. If I mark a location for someone I don't know, I'll contact them using social media saying, "I've done this for you." Every single pansy marks a story of someone who has experienced homophobia on the streets. I don't think it will end. I will always plant them.

The Royal Pavilion, Brighton

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.