I was a neo-Nazi. Then I fell in love with a black woman

- Published

She was a violent white supremacist. But an encounter in prison changed her life forever.

Angela King had gone to the bar expecting trouble. The neo-Nazi had arrived at the local dive in South Florida with a gang of violent skinheads.

King, 23, sauntered in with a 9mm pistol in the waistband of her jeans. She and her friends wore combat boots and coloured braces, their skin emblazoned with racist iconography.

"I had tattoos all over my body. I had Vikings tattooed on my chest, a swastika on my middle finger and 'Sieg Heil' on the inside of my bottom lip, which was the Hitler salute," King says.

They hated black people and Jews and were also virulently homophobic. Plus, one of them was her boyfriend. So King didn't dare to admit that she was secretly gay.

As the group drank they became louder and more aggressive. A large brawl broke out after a man ordering a drink took exception to King's boyfriend.

"He said something about his tattoo and that was it. It took nothing to get my boyfriend swinging," King says.

Angela's tattoos, like those of other white supremacists, were inspired by Norse mythology

King and another woman from her group grabbed the man's companion and beat her up in the bathroom. They fled after hearing the police had been called.

"We drove around all pumped up and started talking about what a race war would be like in the US," she says.

"We talked about how it was OK to hurt people who aren't like us and we decided to go and find a place to rob."

They settled on a convenience store, but farcically it had closed while they argued about who should go in. They eventually targeted an adult video shop, reasoning that pornography "wasn't beneficial to the white race".

"One of the guys went in and pistol-whipped the clerk before stealing money from the register," King says. The clerk was Jewish.

Find out more

Angela King spoke to Outlook on BBC World Service. Listen to the interview

Get the Outlook podcast for more extraordinary real-life stories

King, the eldest of three children, had been raised in a strict conservative family in South Florida. She went to an expensive private Baptist school and attended Catholic Church services each week.

But she had a secret that left her confused, angry and resentful.

"From very early on I felt I was abnormal because I was attracted to people of the same sex," King says.

King kept her sexual identity hidden.

"I knew I had to keep it to myself. My mother used to say to me, 'I will never stop loving you... except you better never bring home a black person or a woman."

Angela hid her sexual identity when she was growing up

King started going to public school when she was 10 after her family moved. She struggled with her weight and self-confidence, and was called names by fellow students. When verbal bullying became physical, she finally snapped.

"When I was 13 a girl ripped open my shirt in front of the entire class," she says.

"I was in a training bra and felt completely humiliated. It just blew the lid off the anger and rage I had been holding on to for so long."

King fought back and realised violence and aggression gave her a sense of control that she had never felt before. She soon became established as the school and neighbourhood bully.

Her parents divorced and while she and her sister stayed with their mother, their brother went to live with her father. Desperate to belong, she joined a group of teenagers into punk rock who were starting to flirt with neo-Nazism.

"These younger skinheads were known as 'fresh cuts'," King says.

"I joined them because they accepted my violence and anger without question."

Listen to Angela King explain how her opinions on race "crumbled away" in prison

The group pasted racist flyers around neighbourhoods at night and started fights with anyone who disagreed with them.

King assumed she had found the right path, because many of their views reflected the casual racism and prejudice she had heard at home.

King was proud of her new identity and wore it "like a mantle" each day. Despite this, little action was taken at school.

In one earth science lesson she put a swastika flag on a model she had built of a moon base. It was left on display for weeks before anyone noticed.

Although the model was taken down, King still received a B grade for it after her mother argued she had the right to freedom of speech. Her parents didn't object to her beliefs, but warned her she was "too blatant about them."

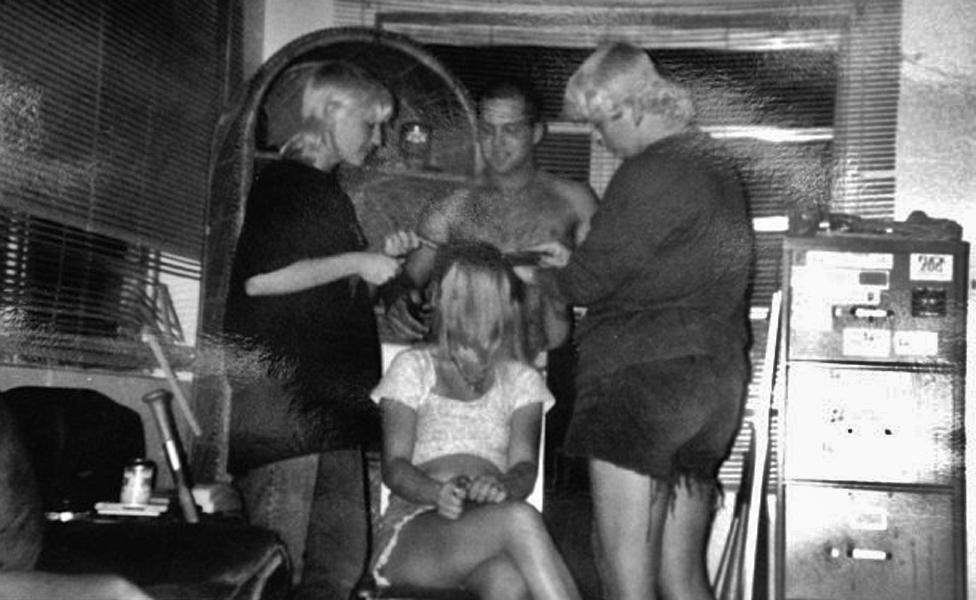

Angela, right, shaving the head of a girl dating a skinhead in her group

King began to hang out with older skinheads and joined a violent white extremist group in her teens.

"They told me that Jews had owned the slave ships and had brought black people to America to endanger the white race.

"It sounds ridiculous but when you are uneducated or trying to fit in, you soak up the new reality like a sponge."

King was asked to leave her school when she was 16 and went to work in various fast food restaurants. Her mother eventually kicked her out for causing too much trouble and she slept in cars and on friends' sofas.

It was around this time, in 1998, that King was involved in the robbery of the adult video shop. Soon afterwards she fled to Chicago with her boyfriend who was wanted for another hate crime. However, she was arrested weeks later and taken to the Federal Detention Centre in Miami.

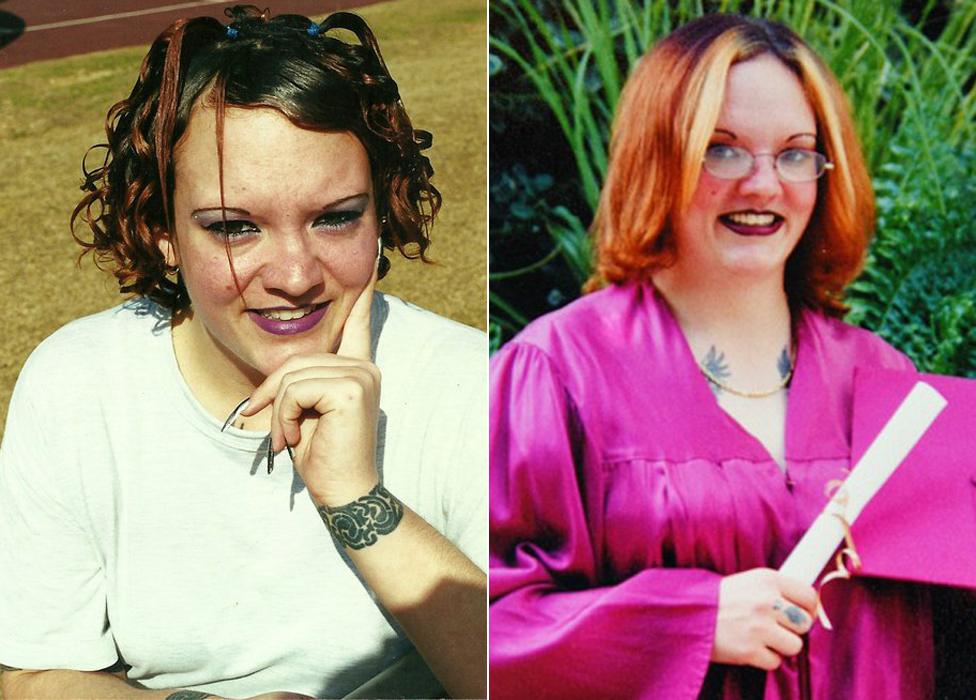

Angela was sentenced for robbery in February 1999

It was the first time she had lived in close quarters with people from different cultures and backgrounds.

"People knew why I was in there and I got dirty looks and comments. I assumed I would spend my time with my back to the wall, fighting," King says.

What King did not expect was the hand of friendship - especially from a black woman.

"I was in the recreation area smoking when a Jamaican woman said to me, 'Hey, do you know how to play cribbage?'" King had no idea what it was and was taught to play.

It was the start of an unlikely friendship and King found her racist belief system crumbling as a result. Her friendship circle widened as she was taken under the wing of a wider group of Jamaican women, some of whom had been convicted for carrying drugs into the US.

"I hadn't really known any people of colour before, but here were these women who asked me difficult questions but treated me with compassion," King says.

With their help, she started to take responsibility for her past actions.

During her first year in the detention centre she was tipped off that a newspaper article was coming out about her case. She told one of her new friends how worried she was about the publicity.

"My friend had a job that meant she got out early to help prepare breakfast. The day it came out she stole the paper and hid it so no-one could read it. She, a black woman, did that for me, an ignorant white woman who was inside for a hate crime."

Angela, third from left, became friends with a group of Jamaican women in prison

King was sentenced in 1999 to five years and moved to the county jail so she could give evidence against one of her former gang. When she was returned to the detention centre she discovered her circle of friends had been moved on to a prison in Tallahassee.

"Suddenly my support network wasn't there," she says. "I was heartbroken."

Meanwhile some new inmates had joined the detention centre, including another Jamaican woman who took an instant dislike to King.

"People said she had been in violent gangs and was a real badass. One day as I passed, she asked: 'How do you even get to be like that?' I stopped and answered her as fully and honestly as I could."

The two women began to talk and realised although they came from different worlds they had had similar experiences on the streets. Slowly the antagonism faded and they formed a bond. They realised over time that their feelings went beyond friendship.

"We realised we had fallen in love with each other. We were like, 'How on Earth did this happen?'"

"We spent a lot of time together talking and shared a cell for a while. It got quite serious but we had to keep it secret."

For both women it was their first serious gay relationship. King's girlfriend was sent on to the jail in Tallahassee before her. King says it felt "like torture" and they wrote to each other via intermediaries. However, the relationship fizzled out a few months after King was transferred to the same prison.

Angela was released in 2001 and earned a degree in sociology and psychology

When King was released in 2001 she was determined not to fall back into old habits. She was also keen to meet other gay people and started by talking to people in chat rooms.

"I was very honest about my past. I found acceptance in the gay community and realised I wasn't alone."

King went to community college to study sociology and psychology. She wanted to understand if her experience of extremism was a common one.

While there she made contact with the local Holocaust Centre, and sat down with a Holocaust survivor in 2004 to share her life story.

"She was very stern, but afterwards she looked me in the eye and said 'I forgive you,'" King says.

Angela with holocaust survivor Leah Roth. She survived four concentration camps but lost most of her family

She has been doing public speaking for the centre ever since. Then in 2011 she went to an international conference where she met other former extremists.

"I was excited to meet other people who had got involved in violent extremism and then got out. I wasn't alone," King says.

She met two Americans who had founded a blog called Life After Hate, in which they shared their stories. They agreed to work together to create a non-profit organisation to help other people leave the far right community.

King was all too aware of the hurdles people wishing to leave white supremacist groups had to overcome. She had tried to walk away following the Oklahoma bombing in 1995.

"I just remember watching all of this horrific television footage of children being pulled from rubble. Then I found out the bomber Timothy McVeigh shared many of my views," she says.

Angela is having her old racists tattoos lasered and covered with other peaceful images

King was under house arrest at the time but also stopped using her phone. One day she found bullet holes across the front of her apartment block. Her extremist friends hinted they had something to do with it.

"It's not something where you can just say: 'I've changed my mind.' There are serious and oftentimes violent repercussions for trying to walk away from something like that," King says.

Without outside support, King didn't feel able to leave. She now uses that experience to help others.

"People in extremist groups wrap their entire identities around it. Everything in their life has to be changed, from the way they think, to the people they associate with, to dealing with permanent tattoos."

The organisation runs a programme called Exit USA that stages interventions. It also offers mentoring and points people trying to leave to different resources.

White nationalists gathered at the University of Virginia on 11 August, ahead of a Unite the Right rally

A group of around 60 former extremists provide peer support to each other. The recent violence in Charlottesville, Virginia, has been particularly difficult to deal with.

"Current events can bring up guilt and shame," King says.

"We are busier than ever and are running on fumes right now."

Life After Hate had its government funding cut back by the Trump administration in June, but King says personal donations from around the world have helped make up the shortfall.

Angela with her co-founders of Life After Hate

Meanwhile she has reached a better place in her own life. Her relationship with her parents has improved and she believes they now accept the fact she is gay although she says she "doesn't care" if they do.

She has also slowly started to forgive herself for her past mistakes.

"I have a lot of healthy guilt about who I was and the things I did to hurt others and myself. But I know I would not have been able to do this work had I not had those experiences," she says.

King is having her old tattoos lasered - a process that started after she left prison. She is covering the faded racist images with new body art. One phrase that now covers her wrist simply says, "Love is the only solution."

More from the BBC

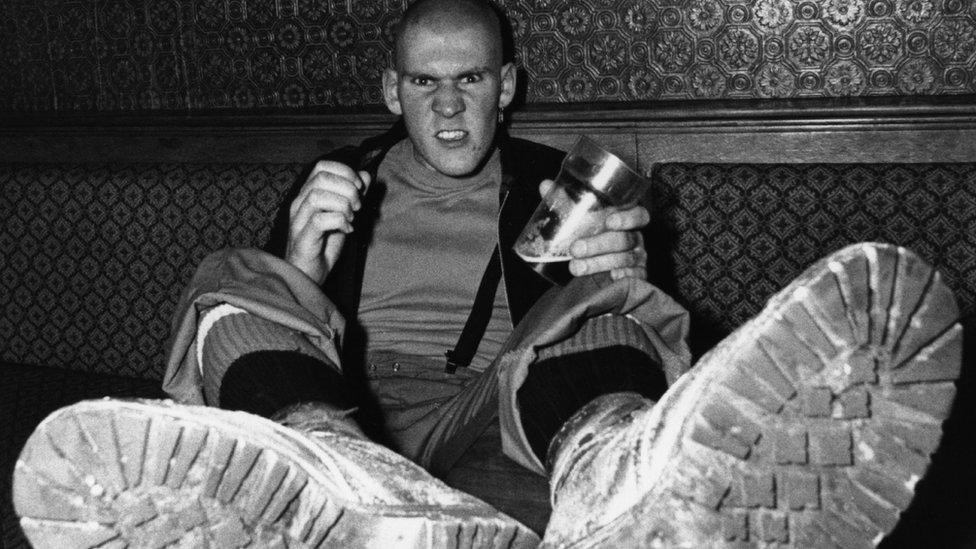

He was a skinhead and the poster boy for one of the 1980s' most notorious far-right movements. But Nicky Crane was secretly gay. Then his precarious dual existence fell dramatically apart.

Images are copyright Angela King, unless otherwise stated

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.