The German schoolboy jailed for writing to the BBC

- Published

The East German secret police went to extraordinary lengths to track down people who wrote letters to the BBC during the Cold War. One of those arrested and jailed was a teenager who longed to express himself freely - and paid a high price.

It was the last day of the summer holidays. For 18-year-old Karl-Heinz Borchardt that should have meant an afternoon on a windswept Baltic beach with his girlfriend, or a few hours spent trying to catch the latest pop songs on his portable radio.

Instead his childhood came to a sudden end.

His mother hurried into his room unusually early and told him to get dressed. Five uniformed agents were waiting downstairs.

Borchardt bought himself time. "I needed time to think," he says. "It could have been for any number of reasons."

Insisting he needed a wash, he started to fling sheets of incriminating texts out of the window. He couldn't know that the secret police already had all the evidence they needed.

It was two years earlier, in September 1968, that Borchardt had written his first letter.

It wasn't easy to keep anything hidden in the cramped two-room flat Borchardt shared with his family in Greifswald, a small town on Germany's northern coastline.

So as he sat down to write at the living room table he covered the sheet of paper with his homework whenever someone poked their head round the door.

The radio sat to his left and Borchardt was glued to the crackly foreign broadcasts coming out of Prague, where Soviet guns and tanks had rolled in to crush an attempt to introduce liberal reforms.

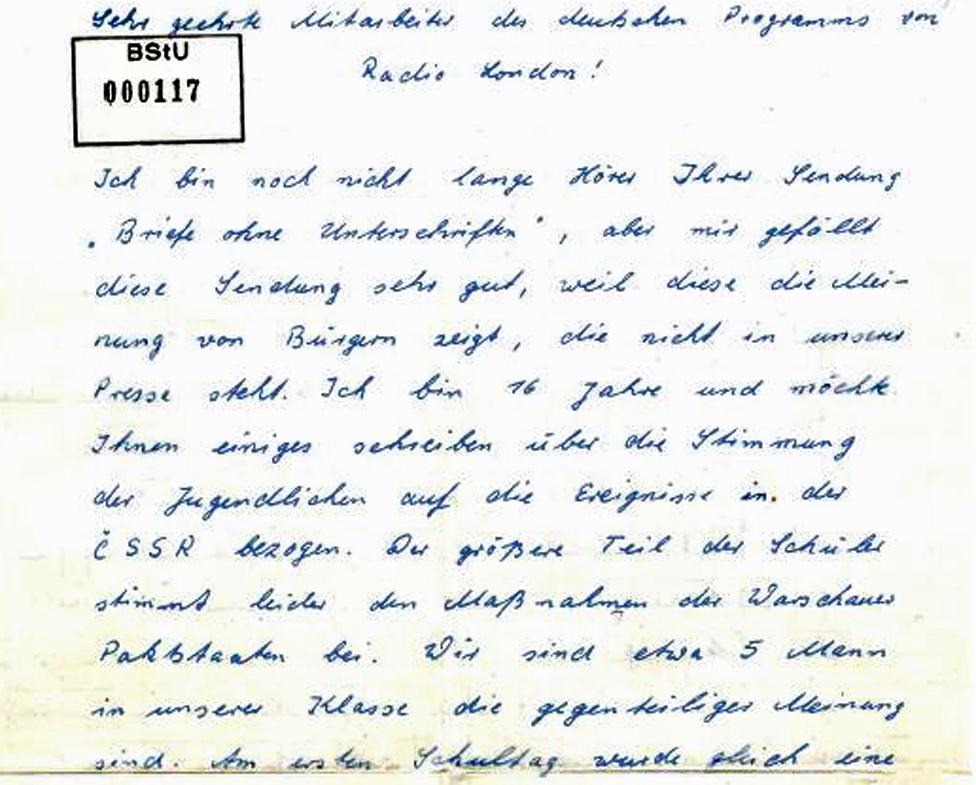

"To the staff of Radio London's German service!" he wrote.

I have only just started listening to your programme, 'Letters without signatures', but I like it a lot, since it airs opinions you don't find in our media. I am 16 years old. I will write to you regularly, mainly about young people and their views on world affairs. In my view, the west did not intervene strongly enough in Czechoslovakia. Does a country which fought so hard for its freedom have to carry on marching to the tune of the Soviets?

Warm regards from a schoolboy

Borchardt signed off with a codename, and addressed the envelope to a Rolf Degner in Kantstrasse 45, West Berlin.

Borchardt didn't know Rolf Degner, he probably didn't even exist. But this was the address he had noted down at the end of the BBC's latest transmission of the programme on its German service.

Listening to a foreign broadcaster was a crime in communist East Germany, let alone writing to one.

Yet Borchardt didn't see any personal risk. He believed he was shielded by anonymity. How could they possibly find him?

He dropped the letter in his local postbox.

Kantstrasse 45 was in central Berlin but it was still a pile of post-war rubble.

The BBC arranged with the West Berlin post office to divert all the letters with this address to a private postbox. These were delivered to the BBC's West Berlin office and then on to Bush House in London.

The west Berlin BBC office at Savignyplatz

The London-based presenter of Letters without Signatures, Austin Harrison, announced different postal addresses every few weeks at the end of the show and East German listeners wrote in their thousands, filling the weekly programme with 20 minutes of anonymous and uncensored letters from people behind the Wall.

Of course the Stasi were listening in too, immediately alerting the post offices to the new addresses so that the letters could be filtered out and passed on to them. But the programme was broadcast on a Friday night and it took a little while for the message to get through to all the regional branches, giving the early correspondents a better chance of getting their post to the desired West Berlin address.

Others handed their letters to West Berlin visitors to smuggle back over the border.

Much to the ire of the East German regime, the BBC programme gave an extraordinary insight into the physical and emotional lives of a cross-section of GDR society for more than 25 years.

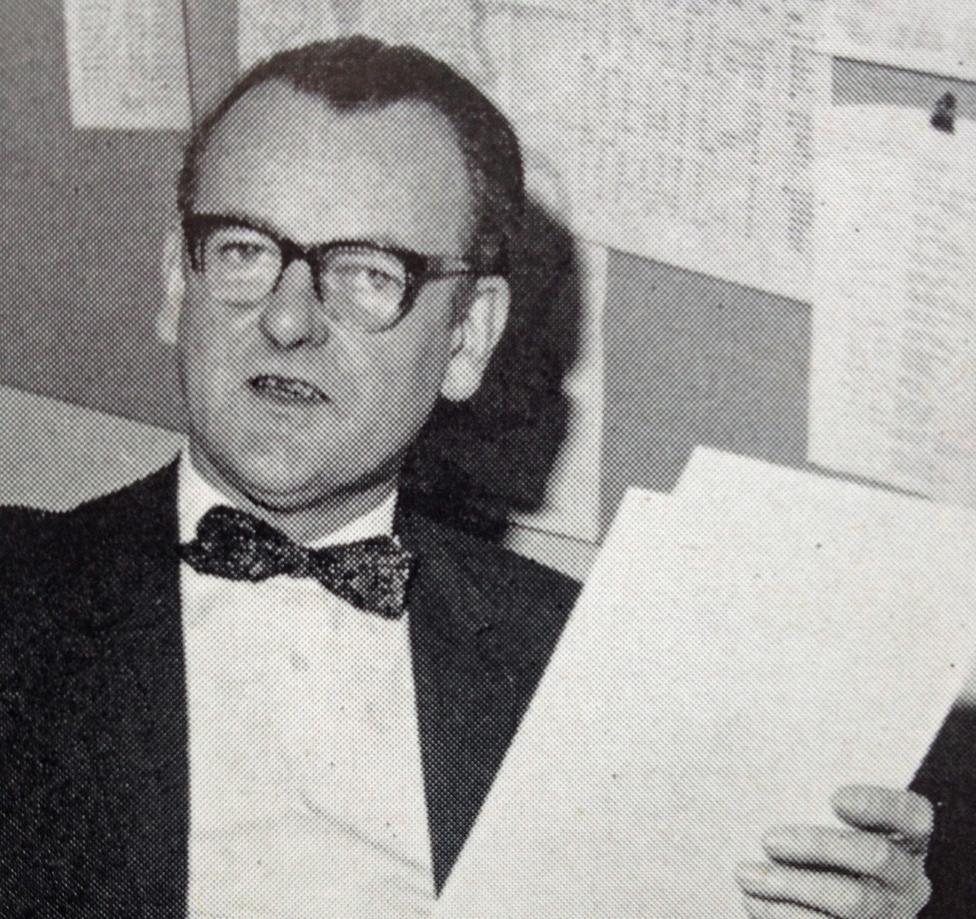

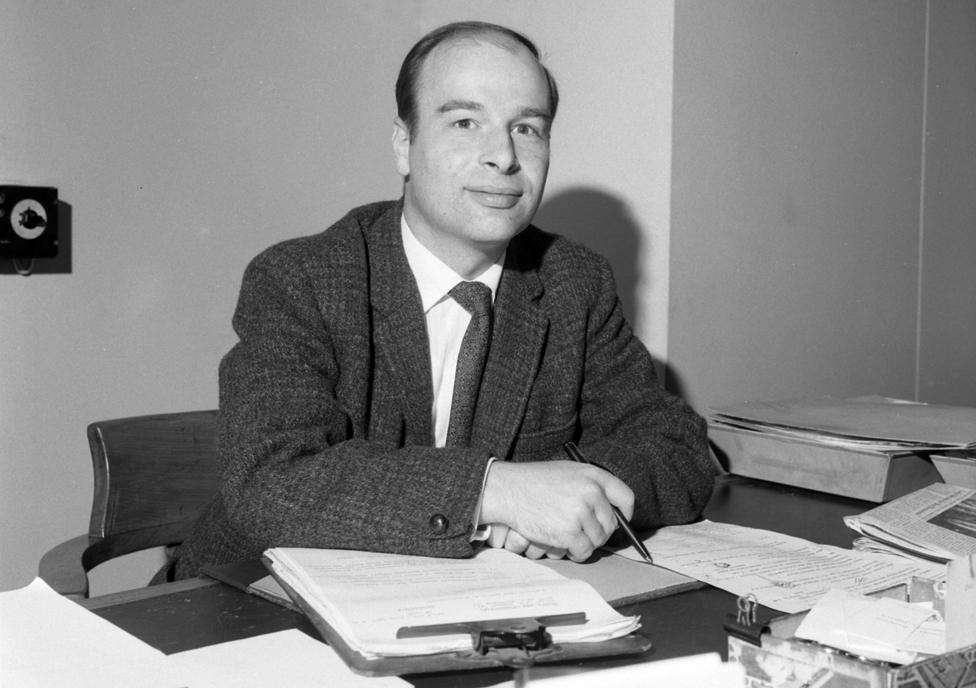

Austin Harrison

"It was like coming up for air," says Borchardt - a form of release for a young, curious mind locked in the suffocating atmosphere of the communist state.

"Freedom of speech didn't exist in east Germany, so they did a detour via London," says Susanne Schädlich, herself a child of the GDR and the author of Briefe ohne Unterschrift (German for Letters without Signatures) a detailed analysis of the BBC programme.

Susanne Schädlich grew up in the GDR and has written a book about the programme

"I felt like I was unearthing treasures," says Schädlich. "The letters are authentic and unfiltered. The writers knew there was no censorship here and they spoke from their hearts."

Many wrote in desperation, appealing to the outside world not to be forgotten as the Berlin Wall was going up.

Others grumbled about shortages of butter, onions and soap and then offered creative substitutes.

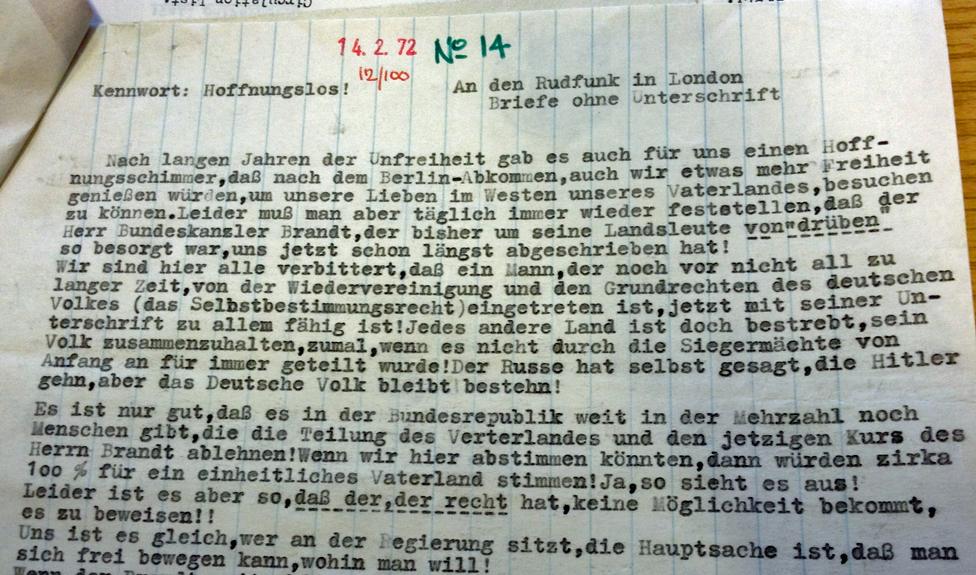

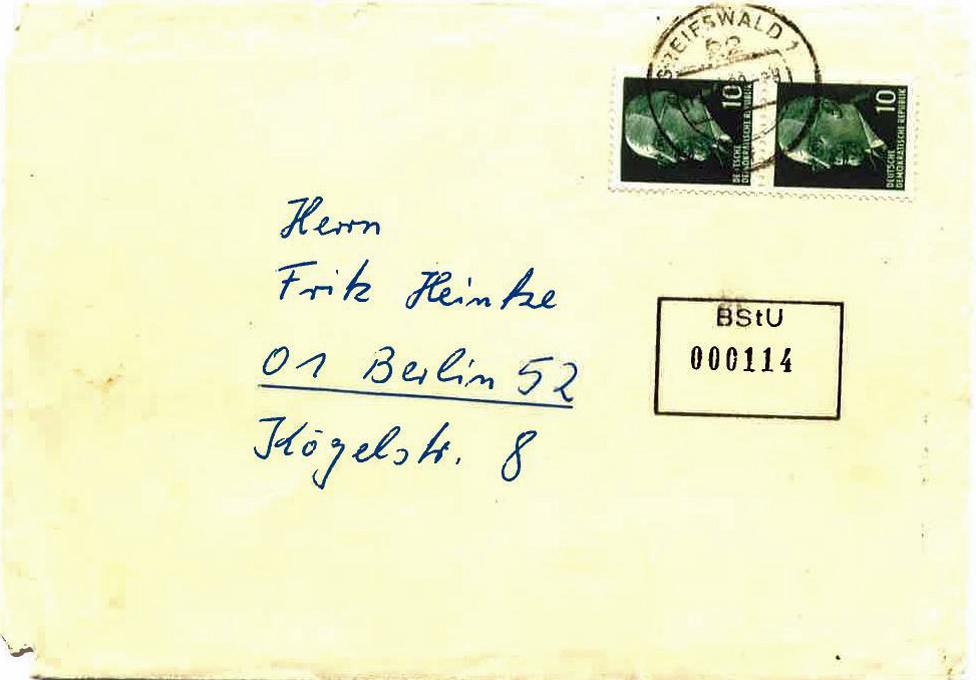

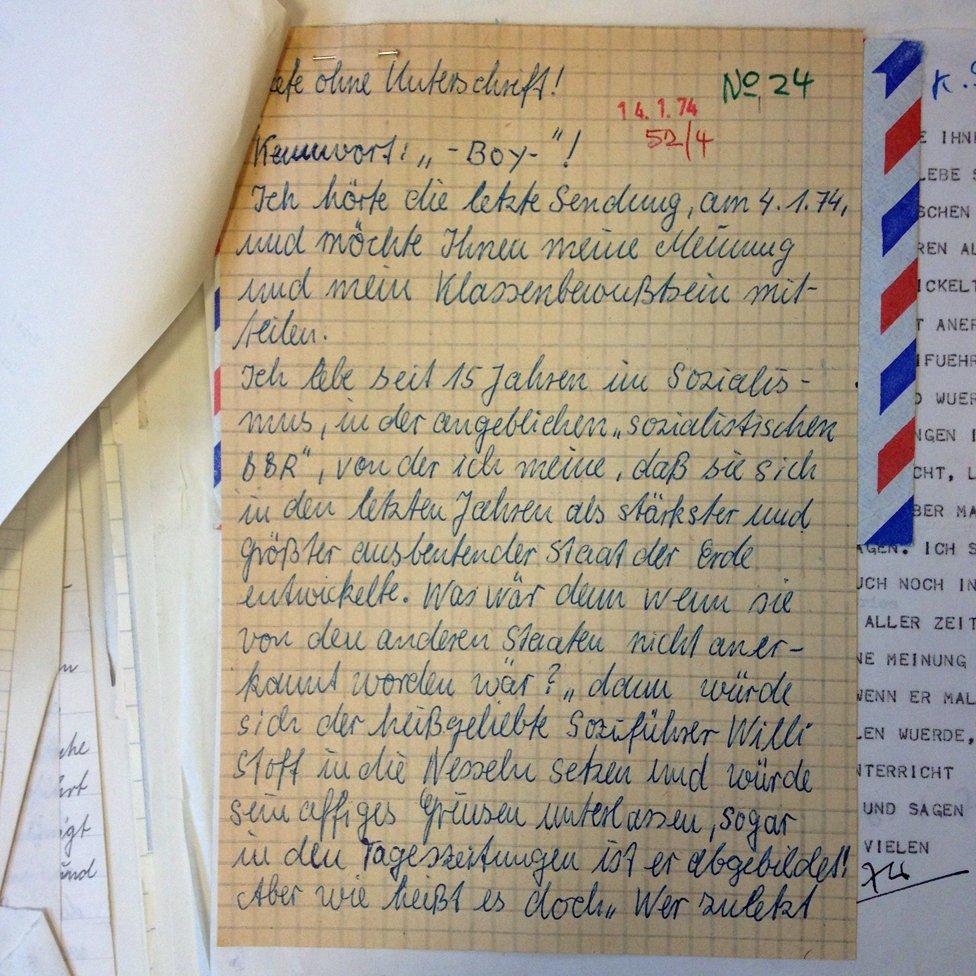

A sample letter from the BBC archives

There was widespread despondency and the fear of being trapped in a repeating cycle of history.

We're being held in a huge concentration camp. There's no escape. We vote for who we're told to. We're simply a herd of cattle which must obey.

(Anonymous letter)

Teachers wrote in, as did farmers, doctors, shopkeepers, even soldiers. An astonishing number of disillusioned children also put pen to paper.

We're being educated in lies. I can't tell truth and lies apart any more. The whole world is dishonest. Politics is just a lying contest. What's the point of life?

(Anonymous letter)

Find out more

Listen to Witness: The German Schoolboy Arrested for Writing a Letter on the BBC World Service

In its own way, the programme offered a small piece of democracy, crafting debate between the opposing views of its varied listeners.

"Some people wrote practically weekly," says Günter Burkart, right-hand man to the presenter, who recalls many years of fascinating work with a group of brilliant and eccentric characters.

The Letters without Signatures team in the studio

Austin Harrison was the only presenter on the show for its 25-year run and he developed a real bond with his listeners, Burkart remembers.

"He thought it was very important that it was always him, that they always wrote to Harrison.

"He talked about 'us'. The family. He and his listeners. It was quite fantastic."

Burkart kept the letters under lock and key in the London office, fearful of spies.

Producer Günter Burkart kept the letters under lock and key

The Stasi not only viewed the BBC as an enemy broadcaster, they specifically saw this programme as a form of psychological warfare aimed to destabilise the regime and incite resistance. They were convinced Harrison was an undercover spy, wooing agents in East Germany.

In the end it was the letter writers they really knuckled down on, and the Stasi were extraordinarily fastidious in their pursuit.

They took saliva samples from the licked envelopes to identify blood groups which they cross-checked with doctor's records. They traced fingerprints on the paper, sourced the ink and collated an extensive archive of handwriting samples.

The Stasi took saliva samples from the licked envelopes

It was his handwriting that caught out Borchardt.

"It just seemed like an ordinary piece of homework," he says, when the pupils in his class were asked to write an essay describing themselves and their later goals in life.

"The thing is, my father thought I had such terrible handwriting he wanted my sister to write it up for me. He nearly got his way."

As ordered, the school passed the essays on to a Stasi agent. Documents show a painstaking analysis of every curve and stroke of Borchardt's pen, comparing it to the intercepted letters from the anonymous schoolboy.

Borchardt wrote to the BBC three more times and with each letter he revealed bolder political convictions.

Dear Mr. Harrison!

I am 17 years old, I grew up in this country (..) but don't think it's fun, always having to say the opposite of what you think. (...)

My honest opinion is that only violence will help us. (...) If Hitler had been overthrown by the people, millions of lives would have been saved.

Warm regards, a schoolboy.

Six months later he was alone in the car with the Stasi. Not a word was spoken.

On arrival at Rostock Stasi prison, he was stripped and searched and put in isolation.

"I was still thinking, I need to get to school tomorrow," he says. "It took me a while to understand what was going on."

Alone in his cell, Borchardt had endless hours to fill. He counted the squares on his blanket, made chess moves in his head, recited maths tables and poetry. Soon he started to long for the interrogations.

After eight months he was convicted for "attempted subversive activities" in conjunction with an enemy broadcaster.

He was sentenced to two years in a youth prison in Dessau.

"You should be happy to live under socialism," were the words of welcome from a young officer as he arrived at the prison.

"Under the Nazis we'd have had you up in smoke a long time ago."

Those words have stuck in his head. The identification with the Nazis.

"The Stasi terminated biographies," says Susanne Schädlich, also drawing links with the methods and terminology of the Third Reich. "The way they went after people, for example, and shut them up."

A sample letter from the BBC archives

And so it was for Borchardt.

School and university were replaced by the daily violence and hard physical labour typical of a GDR youth prison.

He was put on a production line, assembling gas appliances. Safety regulations were unheard of and none of the prisoners really knew how the machines worked.

"I saw bits of machinery flying through the air, fast as a gunshot," he says. "I was lucky, but there were a lot of injuries."

Towards the end of his sentence, Borchardt was offered a golden ticket to West Germany. Brokered by Amnesty International, the West German government had agreed to buy his freedom.

But he refused the offer.

He so desperately wanted to get back to his family and friends, he went on a hunger strike. The GDR relented and he was allowed to stay.

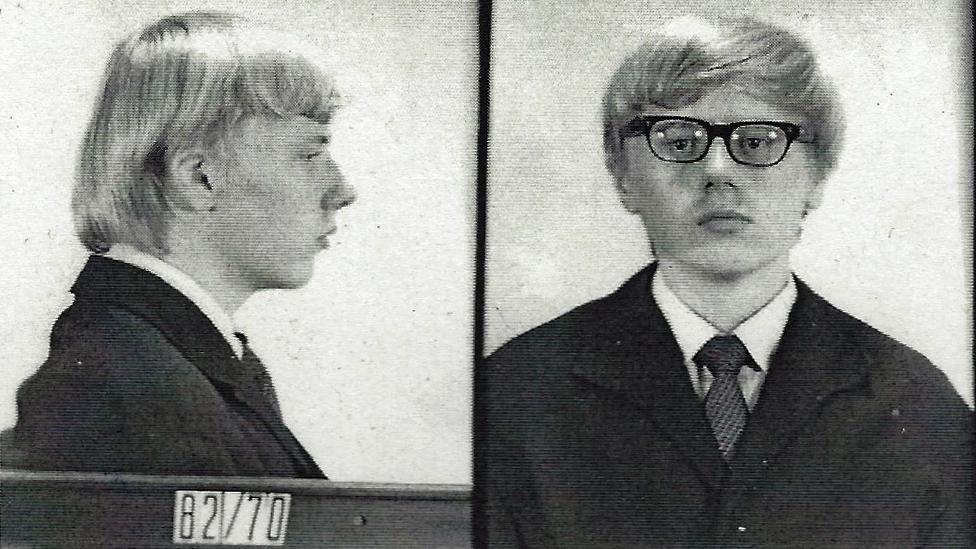

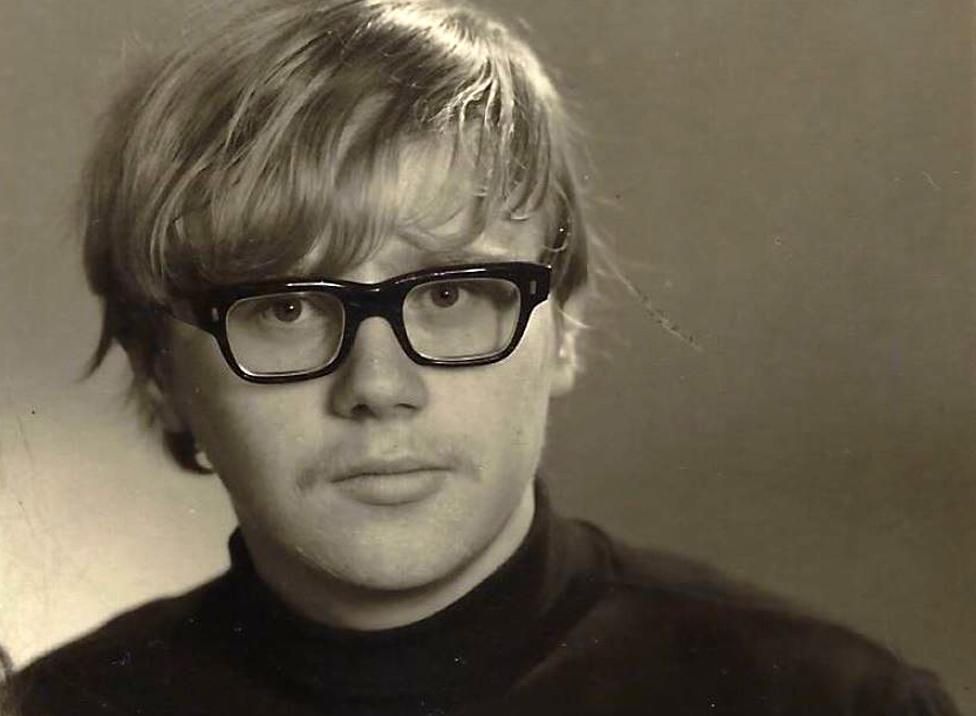

Karl-Heinz Borchardt after his release

"There have been moments when I've regretted that," he says now.

"I overestimated a lot of my friends. When I was walking around town, they would look right through me. They feared for their future, most of them were at university."

Yet his family welcomed him back and he tuned into all the old Western stations he had missed inside. The Stasi hadn't stifled the rebel in him.

Then quite abruptly, in 1974, "Letters without Signatures" was taken off the air by the BBC.

The number of letters had reduced, according to former producer Günter Burkart. Maybe because more were intercepted by the Stasi, but he suggests the foreign office may have had a hand in it.

"Perhaps it was thought with diplomatic relations coming up and recognition of the GDR, it was time to end it," he says.

For many listeners it was a bitter disappointment. The letters kept coming.

"I could just cry. Where is the England which in recent history fought so honourably and bravely against suppression, slavery and injustice? Good night. It feels like 1939 all over again. The lights went out for years."

(Anonymous letter)

With the end of the show Borchardt stopped listening to the BBC altogether.

For the next 15 years he worked as an electronics engineer, and against all the odds studied and got a PhD in East German literature.

Still, he could only get a low-status university job. He was a glorified ticket-seller, he says.

It was only after the collapse of communism and the reunification of Germany in 1989, that he was able to start working as an academic at the University of Greifswald.

He is still lecturing in German literature there today.

More from the BBC

Die Toten Hosen in 1989

When music captures the spirit of freedom it can cross any border. In 1961, Communist East Germany built a wall across Berlin, and tried to seal itself off from the West. But new research shows how concrete, barbed wire and a huge effort by the secret police, the Stasi, failed to silence the seductive beat of rock and roll and punk.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.