Greece in crisis: How European debt problems affect you

- Published

Greece has been in recession for five years, almost a quarter of adults are out of work and the situation in the country isn't improving.

In the latest efforts to turn things around, EU finance ministers have reached a deal on cutting Greek debt and given the green light for the country to receive the next pot of bailout money.

It's been waiting since June for the cash and it means the government there will be able to pay workers' wages and pensions in December.

Greek debts will be cut by 40bn euros (£32bn) and the country will get another 44bn euros (£35bn) of bailout loans.

What is the eurozone?

This is the name given to 17 European countries which use the euro, including France, Germany, Spain and Ireland.

What is the problem?

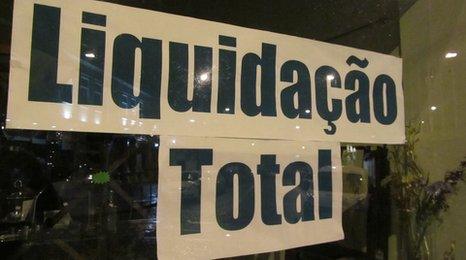

Several countries in the eurozone have borrowed and spent too much since the global recession, losing control of their finances.

Greece was the first to take a multi-billion pound bailout from other European countries, followed by Portugal and Ireland.

Their governments had to agree to spending cuts before the loans were approved.

Greece is still in trouble though and needs more money.

What's going on in Greece?

Many Greek people don't want any more tax rises and job losses, but tough spending plans have been pushed through so the government can receive its bailout cash.

There have been angry protests on the streets and strikes at power stations.

The Greek government is relieved at the latest deal, but the main opposition party, Syriza, doesn't think it goes far enough and called it a "half-baked compromise".

What is the fear?

If Greece is unable or unwilling to keep paying what it owes, the country will effectively go bankrupt and probably become the first country to leave the euro currency.

There are worries that other countries could do the same, threatening the strength of Europe.

Life would also become even tougher for Greek people, who would feel much poorer as their money wouldn't be worth as much.

Governments in other eurozone countries like Ireland and Portugal would have to pay more to borrow money and might have to raise taxes and cut spending to balance the books.

Where does the UK come into this?

As the UK doesn't have the euro, it hasn't contributed to the bailout except through its membership of the International Monetary Fund, which lends to countries around the world.

But some British banks have lent money to Greece and would lose billions if the country went bankrupt.

They would lose even more if the problems spread to other countries like Spain and Italy.

If the banks are hit hard there could be another credit crunch, making it much harder for British people and businesses to borrow cash for loans and mortgages.

Companies in the UK also do many of their trade deals with firms in Europe, so financial problems overseas would affect British business too.

- Published17 November 2010

- Published17 November 2010