From start-ups to grown ups: Social networks face facts

- Published

Facebook has updated its rules but warns users "that something that may be disagreeable or disturbing to you may not violate our Community Standards."

So now we know. Facebook has decided to reveal exactly what it does or does not allow its users to post.

Breastfeeding is ok but buttocks are not, it seems.

Facebook has updated its community standards, external and given users the detail they have long wanted.

It is a sign that times have changed, and Facebook has had to grow up.

Although the social network has recently opened up about how it deals with content reported by users, it has always shied away from detail.

It preferred to talk about guidelines and procedures rather than hard and fast rules.

But that doesn't play well in the media, and it can be frustrating for users left in the dark.

And so slowly and sometimes painfully, Facebook and its competitors have had to face their responsibilities.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said the updated community standards "provides greater clarity around the rules and limits of what you can share in our community."

Now, for example, Facebook has told users that "fully exposed buttocks" and "images of female breasts if they include the nipple" are among images not allowed.

The company is also being more candid about how quickly it deals with reports, and which take priority.

Monika Bicket, Facebook's global head of content policy said: "If somebody reports something for self-harm or for bullying or a terrorism-related report or a threat of physical harm - that sort of report goes to the front of the queue and we try and turn it around very quickly."

Another watershed moment for social media came in February when Twitter CEO Dick Costolo said what many people may have been thinking.

"We suck at dealing with abuse and trolls," he told staff in a leaked memo.

"It's no secret that the rest of the world talks about it every day. We lose core user after core user by not addressing simple trolling issues that they face every day."

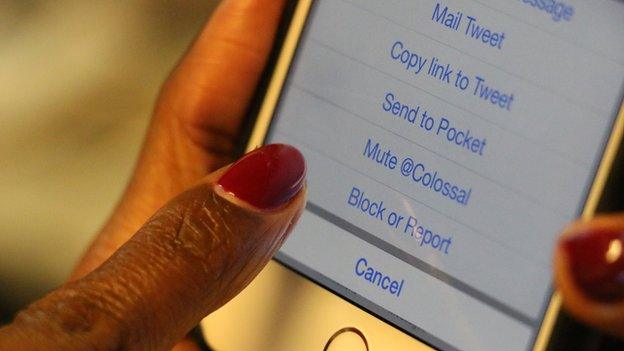

The social network has since made good on a promise to give users more controls and improve the way abusive accounts are dealt with.

Petitions, public pressure and the occasional court case have shone a spotlight on the uglier consequences of Twitter's commitment to freedom of expression.

Twitter has introduced new ways for users to report content and block users on its mobile apps.

A storm of criticism around abuse targeted towards feminist campaigners in 2013 prompted the company to introduce a 'report abuse' button on its mobile apps.

And soon after revenge porn became a specific offence in England and Wales, Twitter updated its rules to ban posting "intimate photos or videos that were taken or distributed without the subject's consent."

Of all the major social networks, Instagram has perhaps had the least unwanted attention.

But even in the relatively tame surroundings of cat photos and #foodporn, there is unsavoury content to be found.

In 2013, Instagram blocked searches for certain terms associated with the suspected illegal sale of drugs.

Images of self-harm and sexually explicit content have also prompted the company to step up its moderation.

In a recent BBC interview, CEO Kevin Systrom admitted the company cannot rely on reports from users alone to police its community.

"It's a balance of relying on the community and also being proactive, to understand what we should do to develop our policies," he said.

Ask.fm launched new resources to help users stay safe in response to criticism of a lack of moderation and support

One company which knows more than most about growing up fast is Ask.fm.

The anonymous question and answer site came close to being shut down when it was bought by Ask.com from its Latvian co-founders in August 2014.

Having attempted to ride out a storm of criticism linked to teen suicides, the company eventually admitted that allowing users to stay anonymous could cause "issues" for some.

Now, the social network presents itself as a model of responsibility, appointing a safety board and providing extensive resources for users to find help.

All this though, has meant it has lost users. Whether it can recover enough to grow again is yet to be proved.

A scandal is some sort is almost guaranteed for any new social network; some ride it out, others disappear without a trace.

YikYak employed geo-blocking technology to stop high school students using its anonymous messaging app

Anonymous chat app YikYak was never designed to be used in schools, but when teenagers in the US started spreading gossip about classmates on the service, the company used geo-blocking technology to stop it.

The outcry in reaction to the "fappening" - which saw nude photos of celebrities stolen and posted online - saw even the relatively loosely moderated 4chan tighten its rules.

The imageboard site added a policy stating that it would remove content when notified of a "bona fide infringement" of US law.

Social networks have disrupted and redefined the way we communicate, they have re-written the rules.

In a post, external on Facebook on Monday, CEO Mark Zuckerburg said "In an ideal world, we would all feel empowered to express everything we want, freely and safely."

In an ideal world, there would be no rules. But as he knows, this is the real world.