Mother's Day: How migration changed our families

- Published

Priscilla Ng'ethe, Zara Rashid and I all have something in common: our mothers are all immigrants.

Our grandmas still live in their home countries of Kenya, Pakistan and Guyana, but we all grew up in the UK.

Our mums made the journey abroad to England and by doing so they changed our lives forever.

Were they happy with the decision to leave - and was it even their choice? On Mother's Day, this is their story.

'I can't hug them'

Growing up in a predominately white town, I struggled at times. I didn't 'look' like all the other kids.

My nose and lips were significantly bigger and my mum didn't sound like all the other mums.

That's because my mum Maureen Dasilva Peers was born in Guyana, South America.

She came to the UK aged just 17.

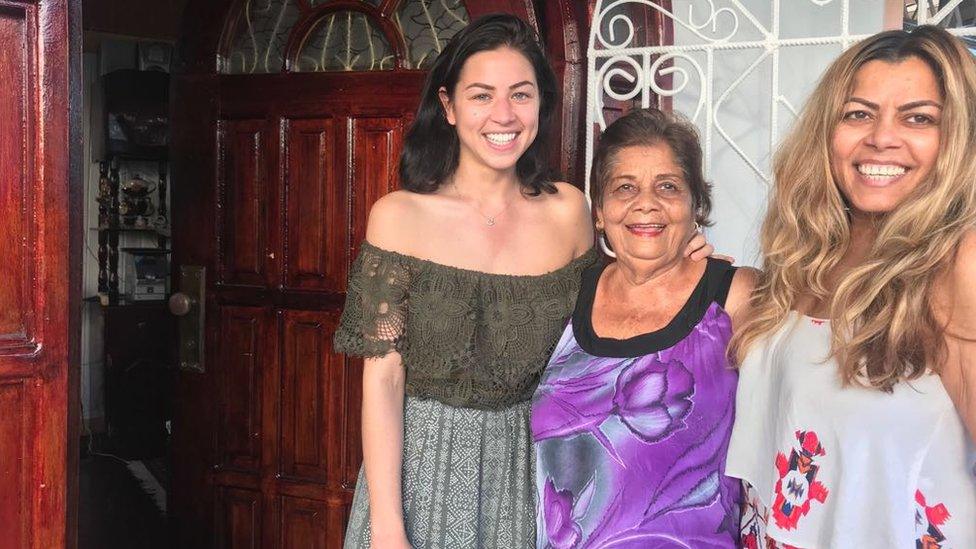

Mum is one of eight children. Her mother, 81-year-old Habula Karamat, still lives in Guyana. All eight of her children emigrated, searching for a better life overseas.

I visited my Nanny in Guyana recently. She got emotional when I asked her about her children being so far away.

"Many days, when I lie in my bed, I miss my kids," she told me tearfully.

"It's a hard thing. It's a painful thing, when I think they're miles away from me. I can't touch them. I can't hug them."

'Girls pay for big lips like mine'

When you're young all you want is to fit in. At my school, all the mixed race girls grouped together. Maybe it was because we all looked similar or we could just relate.

We knew our mums were different and because of that we were always seen that way.

It is only now at the age of 27 that I have finally started to embrace and love who I really am.

As my mum reminds me, 'girls pay for big lips like mine'. It may sound silly, but these were the issues I battled.

'You need to go to England'

You might assume my mum wanted to come to England for a better life. That couldn't be further from the truth.

My mum didn't want to leave Guyana at all.

"It was never my decision to leave, I was happy in Guyana," she says.

"I had friends, all my brothers and sisters around me, it was home.

"One day my dad just said: 'You need to go to England, get on a plane and go.'"

He said she'd have "a better life, better healthcare and better prospects".

But mum quickly realised England wasn't the utopia she was promised.

One of her most vivid memories was after first moving here, having the option to go on benefits.

She says she was adamant not to do that.

She chose to collect money for the Red Cross, and would go knocking on doors. One day still resonates with her.

"I knocked on this elderly lady's door and she said: 'Go away, I don't give money to foreigners!'

"I went home and cried and I thought: 'How can people be so rude?!'"

'Abroad is like home'

Priscilla Ng'ethe moved to London from Kenya with her mum Lucy when she was just a baby.

Priscilla and her mum Lucy

Lucy followed her partner, who had come to England as an asylum seeker in 1995.

"Everybody is a family back in Kenya. You know all your neighbours and you are a community," Lucy says.

She now considers England her home: "I have the same rights. Access to healthcare, food, shops. If there is discrimination it is hidden. I've never experienced direct racism."

The thing that makes people move can be entirely different for different families.

But what does the word "family" mean for Priscilla?

"Family means a unit. When I think of family I think of home," she says.

"I can be going through the worst time and I can just go talk to my mum and I feel at peace and calm. She is my mother. She knows exactly how I feel. There is that bond, that connection."

The 24-year-old recently visited Kenya to celebrate her great grandmother's 117th birthday.

Left to right: Priscilla's mum, grandmother, maternal great grandmother and Priscilla

Elizabeth Gathoni Koinange was one of the oldest people alive.

"For my children, abroad is like home. All of my children have gone abroad," Elizabeth said before she died in November last year.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The only Asian in the village

Zara Rashid's mum left Pakistan 27 years ago for Moore, Warrington, which she's now happy to call home.

Zara and her mum Gulshan

But coming here with no language and no family was a difficult process.

When Zara's mum Gulshan Rashid arrived she couldn't speak any English.

"Not only could I not communicate but I didn't know my way around.

"My husband was working abroad. I had no relatives, no friends, no one to help."

Zara's mum was the only Asian in the village. She couldn't drive so her only option was to wait for the hourly bus.

Hearing Zara's story there are many similarities her and my mum faced.

The cultural difference is what all the mothers had to face. I believe this is why they have had to be incredibly strong.

For about five years Zara's mum worked as a dinner lady in her primary school. Since then she has been a full-time housewife.

Zara and her family

For Zara family means: "Being able to come back from the outside world and not have to feel judged about your actions.

"It's where there should be support and love as well as guidance.

"There's laughter, happiness, and from my experience, arguments."

Part of being a mother is about making sacrifices. Something all our mums know too well.

Learning about all their stories has made me realise one thing. Packing up their entire lives and moving abroad? Leaving everyone and everything they knew behind?

I couldn't do what our mums did. Could you?

You can listen to Grandma, Guyana and Me the documentary on BBC World Service on 13 March at 1.30pm.

Follow Newsbeat on Instagram, external, Facebook, external and Twitter, external.

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 every weekday on BBC Radio 1 and 1Xtra - if you miss us you can listen back here.