Fuel prices: A really simple guide to why they go up and down

- Published

When you pull up at the pumps, you're probably not thinking about the knife-edge, geo-political tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

You're thinking about how much it's going to cost to fill up and which bag of sweets to get for the glove box.

But what's happening thousands of miles away in the Middle East has an impact.

So here's a really simple guide on what causes the price of fuel to go up and down.

Tax is the big one

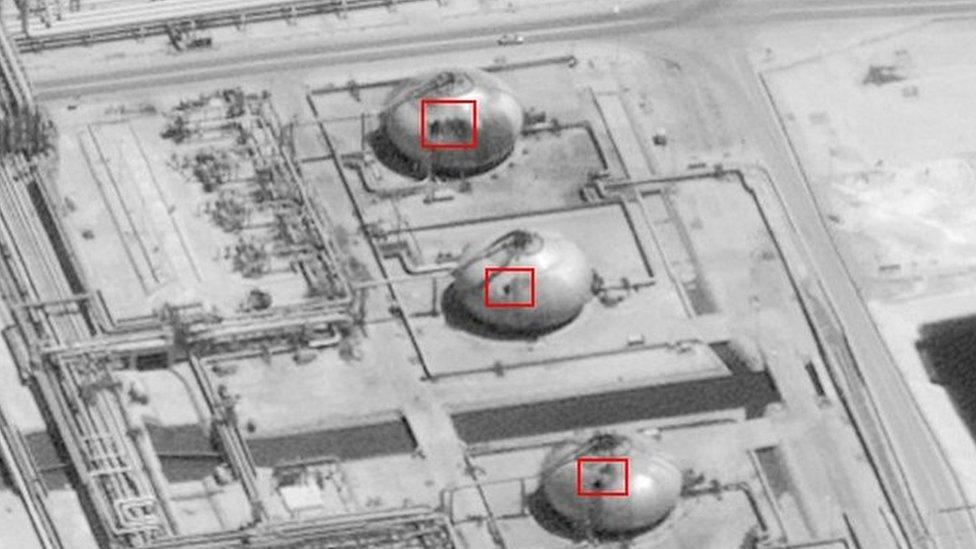

An attack on Saudi oil facilities has knocked out 5% of the world's oil supply.

It's got people worried we're about to see a big jump in the price of petrol and diesel.

Not necessarily.

"The biggest thing isn't what's going on in Saudi or Iran, it's the Chancellor of the Exchequer," says Phillip Gomm from the RAC Foundation.

That's because around 60% of the price you pay for fuel is tax - a mixture of fuel duty and VAT. So just because the price of oil doubles, that doesn't mean we'll see the same jump at the pumps.

It's too soon to say how much the price will go up

The wholesale price is how much the oil costs when it leaves the refinery - that's the price retailers pay for it.

When supply is disrupted - such as an attack on an oilfield - wholesale prices go up.

Abqaiq has the world's largest oil processing plant

"We'll see the wholesale price go up quite quickly but then it takes a couple of weeks for that to get passed on to drivers," says Philip.

But because we don't know how long the supply will be disrupted, it's impossible to predict how much fuel costs will increase, or for how long.

The exchange rate is important

Oil is priced and traded in dollars. So if you have a weak exchange rate - how many dollars you can buy with sterling - it's going to cost more in pounds to buy that fuel.

Instability doesn't always mean big price rises

"If other suppliers think there's a chance to sell more fuel because the Saudi supply has been interrupted, they will flood the market with more of their stock. If they've got spare oil, they'll try and shift a bit more," says Philip.

He says there isn't a shortage of oil across the globe, it just depends what's going on.

"The market has adjusted without blinking over the last two years to the loss for political reasons of over two millions barrels a day of production from Venezuela and Iran," says Prof Nick Butler, who's an expert in international energy policy.

Of course, if tensions in the Middle East spill over into conflict, it's a different story.

Production facilities, trading routes and pipelines which thread through the region could all be vulnerable to future attacks - which could push up prices long-term.

The cost of a barrel of oil is soaring since the Saudi attack - roughly $65 (£52.20) a barrel, depending on when you read this.

But, according to Philip Gomm, "we're miles off the $143 (£114) a barrel in 2008 - so we're a long way from historic highs.

"It's a brave person who'll predict how much prices will go up."

- Published16 September 2019

- Published17 September 2019