Police racism inquiries in the UK: Do they change how things work?

- Published

Do the police racially discriminate against people from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities?

That's what a new investigation is going to ask in the wake of George Floyd's death and anti-racism protests.

It's being done by the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) - which handles complaints about officers' behaviour in England and Wales.

Some of the more controversial parts of policing, like stop and search tactics, are going to be looked at.

It's the latest in a long line of reports focusing on racism.

There's sometimes criticism these reviews don't change things - and can be used to give the impression of taking action while ignoring real problems.

We've looked at some of the biggest ones focused on policing.

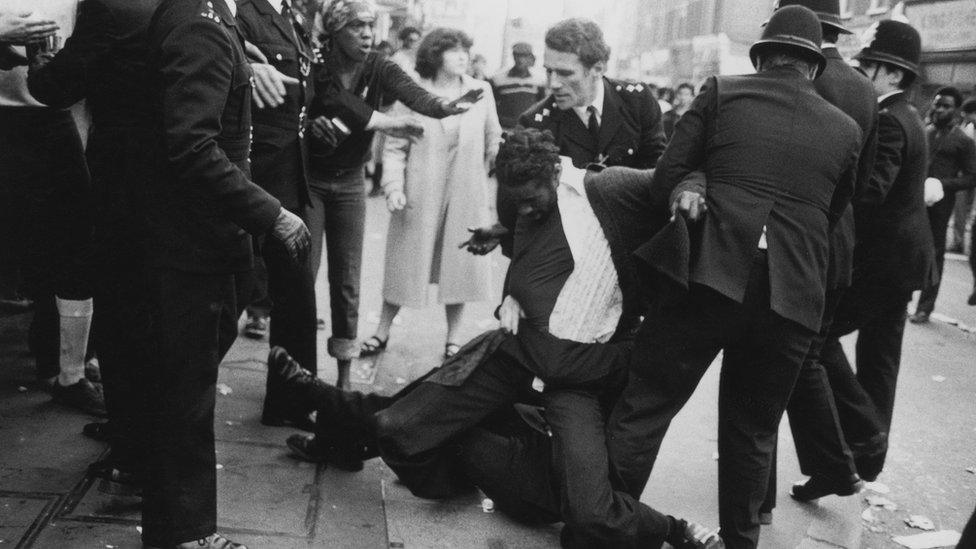

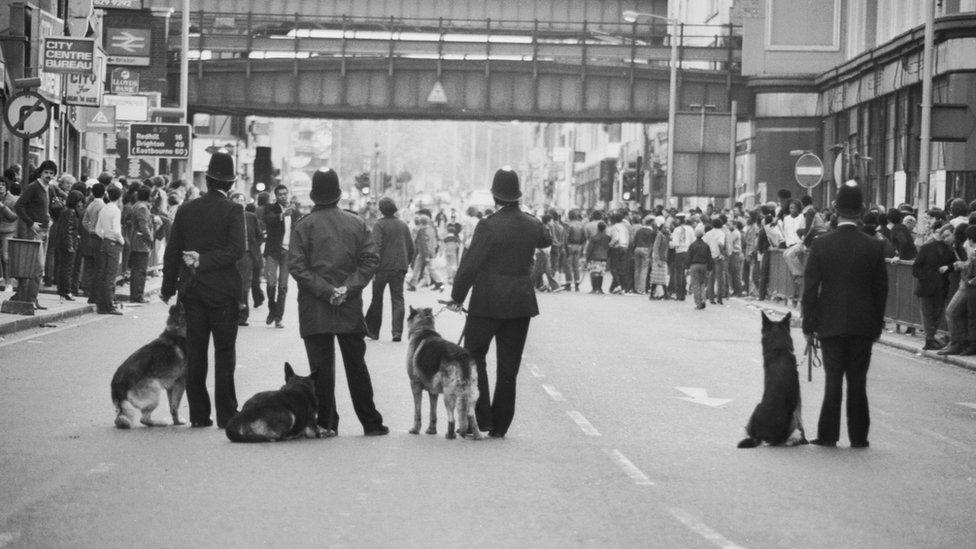

The Brixton riots

About £7.5m of damage was caused in Brixton over three days

In April 1981, violence broke out over three days in Brixton in south London. Around 300 officers and 65 members of the public were injured.

The trouble started after unproven rumours about a young black man being badly treated by the police - which came at a time when tensions were already high.

Days before, a plan to cut street crime in the area had led to a thousand people being stopped by officers in less than a week.

Police only needed to suspect someone might be planning a crime to stop and search them.

Nearly 300 arrests were made during the trouble

The Scarman report

The investigation into what happened in Brixton was written by Lord Scarman. It found the riots weren't planned - but happened after "a loss of confidence" in the police.

It said resentment had built up over the search tactics used - which wasn't helped by unemployment levels.

Batons raised during the Brixton riots

Scarman found there was "racially prejudiced conduct by some officers".

But he said there wasn't evidence of "institutional racism", where racist behaviour becomes "part of the normal behaviour of people within an organisation".

What was recommended?

The report called for building better trust with the local population, including recording all stops made by officers.

It also wanted to see more BAME people working in the police and new approaches to how recruits were trained.

It's thought about 5000 people were involved in the riots

What happened?

Three years after the riots, some changes were made in the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984.

Officers then did have to record all stops and searches under new powers.

Guidance on what justified stopping someone was made stricter, and in 1991 another change meant the ethnicity of who was being stopped also had to be logged.

The Scarman report warned about inequalities building up in inner city areas

The next decade saw a small rise in BAME officers. At the time of the riots, only 143 officers in the Metropolitan Police were from those backgrounds - that was 0.6% of the force, external.

By 1991, it had gone up to 556 officers - or 1.6% of the total.

That was still not in line with how many black, Asian and minority ethnic people lived in London. That year they made up 20% of the capital's overall population.

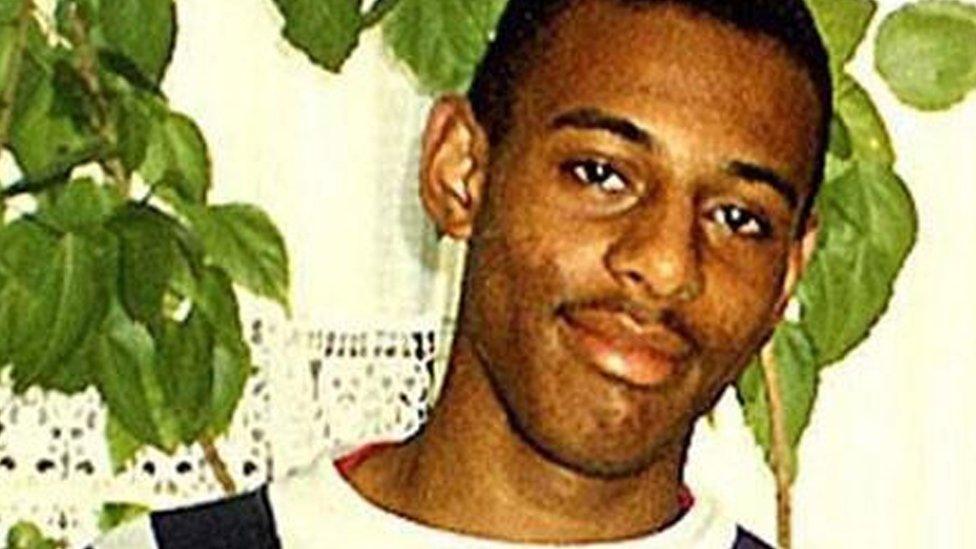

Stephen Lawrence's murder

In 1993 black teenager Stephen Lawrence was stabbed to death by a gang in south east London in a racist attack.

Two white suspects were charged - but the case was eventually dropped, with prosecutors saying the evidence wasn't reliable.

Stephen Lawrence was waiting at a bus stop when he was attacked

No-one else was put on trial and it reignited debates around policing and racial discrimination.

The 18-year-old's family began campaigning to have his killers convicted and locked up.

The Macpherson report

Four years after Stephen Lawrence's murder an investigation started into how his case was handled - and why no-one had yet been jailed.

The Macpherson report was published in 1999, saying there was "institutional racism" in London's Metropolitan Police.

It highlighted a "failure of leadership" and suggested wide-ranging changes.

In 1995, a memorial to Stephen was put on the pavement at the spot where he was stabbed

What was recommended?

The Macpherson report wanted police to show "zero tolerance" for racism in society.

It said there still weren't enough BAME people working as officers.

The report said stop and search tactics were useful when used the right way - but it wanted the police to actively review the ethnicity of people being stopped, to look out for patterns that might suggest discrimination.

Macpherson also wanted something called "double jeopardy" laws scrapped.

They prevented people from being put on trial for the same thing twice, and were significant because of the failed case into Stephen's murder.

What happened?

Double jeopardy rules were ditched in 2005. That eventually led to Stephen Lawrence's killers being jailed - nearly 20 years after his death.

Stephen's mum Doreen after meeting with the Met Police in 2013

In 1999 - when the report came out - 4.4% of officers were from BAME backgrounds and by 2011 that had gone up to nearly 10%.

But it was still well short of comparability with the 40% BAME proportion of people living in London.

Stop and search statistics then began being regularly published.

A report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission in 2010 suggested that a black person was six times more likely to be stopped, external than a white person in England and Wales. An Asian person was around twice as likely.

The authors said more research was needed into why that rate changed so much from one police force to another.

When it comes to statistics based on population averages though, there's a warning from an expert team in government that gathers detail on ethnic groups.

The Race Disparity Unit says we shouldn't read too much into stop and search information covering the whole of England and Wales.

It says that's because the tactic isn't used evenly from force to force, and a high number of stops in one place involving a specific ethnic group can skew the overall stats.

Its website points to the fact 79% of all searches of black people in 2018-19 were in London alone.

England riots

Mark Duggan's death quickly saw trouble spread across London

In August 2011, violence broke out in north London after 29-year-old Mark Duggan was controversially shot dead by police.

Officers said he was a known gangster reaching for a gun, but other accounts challenged this and questioned the circumstances of how a gun was eventually found.

In the end, the inquest into his death said that he had been lawfully killed.

Trouble spread from London to Birmingham, Bristol, Liverpool and Manchester.

More than 3,000 people were arrested - with shops looted, businesses set on fire and houses broken into.

Five deaths were linked to the violence.

The 'After the riots' report

The Riots, Communities and Victims' Panel found "no specific cause" for the trouble, but said it wouldn't have spread if police had acted more "robustly" in London.

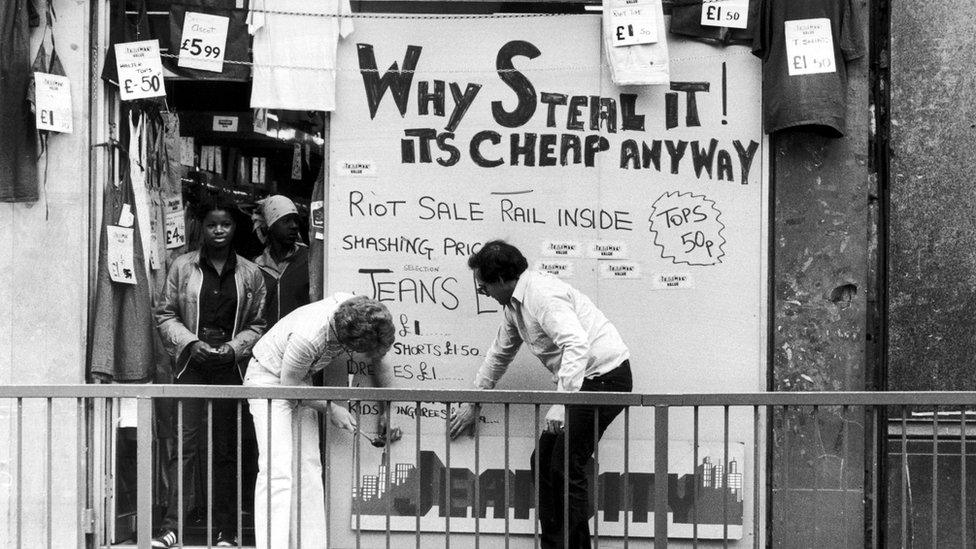

Its report - called "After the riots" - said the people who got involved wanted anything from stolen new trainers to the chance to "attack society".

It took five days for the trouble to be brought under control

What was recommended?

It said stop and search tactics were a big reason behind resentment among young black and Asian men - and police forces needed to focus on better relationships.

Specifically, it wanted to see higher police satisfaction levels among black, Asian and minority ethnic communities.

Rioters set up road blocks in some areas

What happened?

Trust in the police has gone up since the riots, according to the latest official statistics.

The most recent Crime Survey, published in 2019, says 70% of black people said they had confidence in their local force - up from 65% in 2011-12.

The figure for Asian people is 78% - up from 76%.

For white people it's stayed steady - at 75% in both 2011-12 and 2018-19.

The report into the riots said some people used it as an opportunity to steal things like clothes, shoes and TVs

The number of stops has come down significantly for all ethnicities in the time since the report.

In 2011, there were 113 stops for every 1,000 black people. In 2018-19, it was 38 stops.

The same statistic for Asian people in England and Wales went from 37 to 11 stops.

For every thousand white people, there were four stops in 2018-19 - compared to 17 stops in 2010-11.

The government says stop and search powers are needed by police

You might also like:

Does policing change after racism enquiries?

Changes happen, whether they are the right changes, fast enough or go far enough will always be up for debate.

In 2019 England and Wales had the highest number of BAME police staff ever recorded.

But it's still a significantly lower proportion than the number of BAME people in the overall population.

Some see a link between the recurring themes of recruitment problems and stop and search.

Last year the government said it was giving police more powers to use stop and search - reversing some of the changes that had come before.

It said it was aimed at tackling rising knife crime, which is at the highest-ever recorded level in England and Wales.

In early July, Sir Thomas Winsor - Her Majesty's chief inspector of constabulary - said disproportionate use of stop and search on black men especially was making it harder to make police forces more diverse.

He blames the resentment it can build up towards officers.

There's no clear deadline on when the latest review will come back with recommendations.

But the Independent Office for Police Conduct says it's about "identifying where we are seeing good and bad practice, and where there are then opportunities to drive real learning and change."

Follow Newsbeat on Instagram, external, Facebook, external, Twitter, external and YouTube, external.

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 weekdays - or listen back here.

- Published27 July 2020

- Published30 July 2020