Good Friday Agreement: Growing up after the peace deal

- Published

(L-R) Isabel, Ollie and Rachel Hume are proud about the role their grandad John Hume played in the Good Friday Agreement

You might have photos of your grandparents on your walls at home. But they're probably not like Ollie's.

"Some of my friends were over here the other day and they saw the photo with Bill Clinton and the Nobel Prize," he says.

"And they think it's crazy."

The picture Ollie's talking about shows his grandad, John Hume, posing with the former US president after being awarded the prestigious award in 1998.

In that same year John, the leader of Northern Ireland's Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), had signed the Good Friday Agreement.

The peace deal ended almost 30 years of violent conflict in Northern Ireland known as the Troubles.

Thousands of people died as a result of bombings and shootings carried out by loyalists- who wanted Northern Ireland to stay in the UK - and republicans - who wanted Ireland to become one country.

Since the 1960s growing up or living in Northern Ireland had meant having to worry about being caught up in attacks.

The Good Friday Agreement also created a new generation - those born after it was signed, who've come to be known as "peace babies".

So what does it feel like to know your grandad played a key part in ending the worst of the violence?

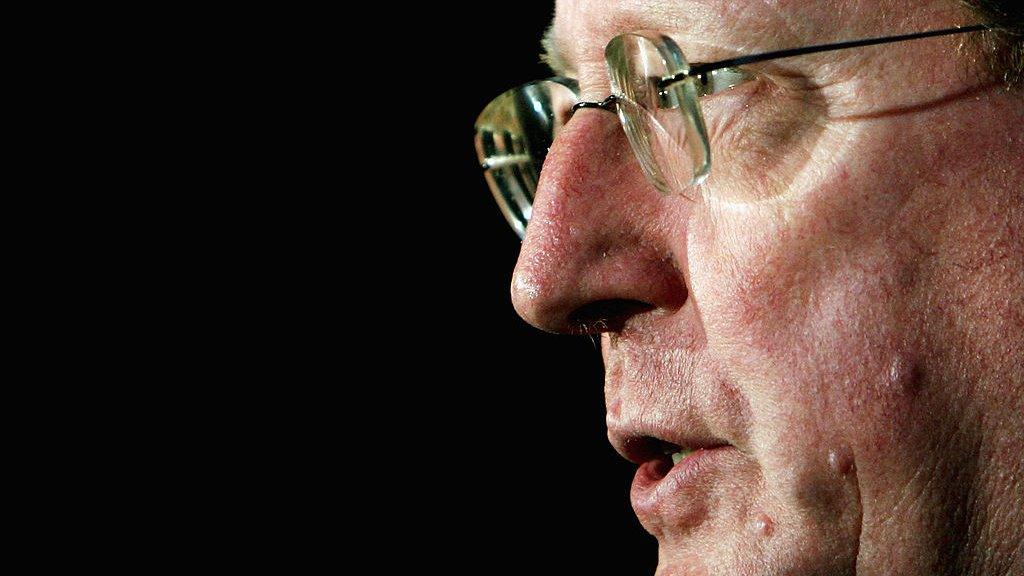

John Hume with his wife Pat after his election in 1998

John Hume's three grandchildren, who've never spoken to the media before, say his legacy is "weird" for them.

"Because to me he's also just my grandad," says 17-year-old Ollie.

"I'm obviously proud of him and to say 'that's my grandad', that's pretty cool. It just shows that people who are in some ways different, that they can get along.

"And that it doesn't have to be just this endless conflict for something that there's no real end result to."

"I don't think I really realised how important he really was to the country until he died. And he was on the news for like five days straight," says 14-year-old Rachel.

Isabel agrees, and says she remembers her grandad as someone who would "always have the crossword out" and loved stealing sweet treats.

"I think my granny had to hide all the chocolates and sweets and yoghurts, and basically anything with sugar in it because he'd hunt them down," the 19-year-old says.

Looking to the future, Isabel says she hopes "there will be steps forward rather than steps backwards".

"I guess in terms of peace and creating more of everyone getting along, and religion or nationality aren't as much of a difference and aren't as much of a dividing factor," she says.

John Hume's grandchildren were all born after 1998, so are all part of the peace baby generation.

Kerrie Patterson was born in 1998 - literally minutes after the Good Friday Agreement was signed - making her the first peace baby.

The 25-year-old, from Lisburn, in Northern Ireland, now lives across the border in Dublin.

Kerrie says her parents gave her the middle name "Hope" to signify a more positive future for the younger generations.

But does she think they'd be happy with how things have changed 25 years on?

Kerrie's parents gave her the middle name "Hope" because of the Good Friday Agreement

"We've had so many opportunities in my generation and the community's a lot more integrated than it was back then," she says.

"I think they they would still like to see more progress in terms of the government and getting Stormont back up and running.

"But for the most part they're really proud of how I've been able to have such a happy and healthy childhood and that that's been echoed throughout Northern Ireland for my generation for the most part."

Kerrie is someone who's grown up in the shadow of the Good Friday Agreement her whole life, but what does it mean to a slightly younger generation?

We asked a group of 16 to 18-year-olds at the high school in Dromore, a town of about 6,000 people that's 20 minutes outside Belfast.

They were quite honest and said being a "peace baby" meant a bit less to them because of how much things have changed in the last 25 years.

Teenagers at a high school in Dromore are aware of how much has changed since 1998

"I feel like for our generation it doesn't mean much because we're very ignorant to the pain and the suffering that our parents and grandparents went through," says Shauna, 17.

"As a generation, we will never understand that."

Charis, 16, agrees, telling me: "I really haven't heard much about it but I suppose it's something I always take for granted.

"My mum just brought up a story about how she had to go through an Army checkpoint. I really did not think that that would have happened in her time, it took me by surprise."

If you ask the four teenagers what they think of if they hear "the Troubles", straight away the reply is "Derry Girls".

The hit Channel 4 sitcom was inspired by writer Lisa McGee's experiences growing up in Northern Ireland in the 1990s.

David, 16, is quick to reference a scene in the first episode where British soldiers search the main characters' school bus at a military checkpoint.

"It does just seem [like] a completely different world what they're describing, compared to what we have now," he says.

Derry Girls is set in Northern Ireland in the final years of the Troubles

And it's clear the show's opened this generation's eyes to what things were like for their parents two decades ago.

"I think we never worry about violence," Shauna says.

"We don't get on the school bus and fear for our lives like people did. I think we're very separate from that, and it feels like ages ago for us."

Agreeing with her schoolfriends, Toni, 18, says: "I mean, I'm glad I have peace.

"I would not want to have lived the life that my parents have told me that they've had to live."

Follow Newsbeat on Twitter, external and YouTube, external.

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 weekdays - or listen back here.

- Published3 April 2023

- Published4 May 2022

- Published12 April 2023

- Published11 April 2023

- Published10 April 2023

- Published7 April 2023