Accessibility in gaming: 'When we all play, we all win'

- Published

Sightless Kombat is an avid gamer who regularly streams his achievements to his followers

"How do you play video games?" is a question Ben gets asked a lot.

The answer isn't as simple as you might think, because he can't see.

Ben - who prefers to be known as Sightless Kombat, or SK - is a gamer without sight who regularly streams on Twitch.

As you might expect, he gets lots of questions from followers, and has set up a chatbot to answer some of the common ones.

"Even using the term gamer without sight, as much as you might think it clears things up, it doesn't always make it absolutely crystal clear for some people," he says.

To play his favourite titles, SK relies on audio cues, tweaks to in-game options and "occasionally, a fair amount of practice".

And SK likes a challenge - on his YouTube channel you can see him tackling God of War Ragnarök on the hardest difficulty, taking down "the two hardest optional bosses in the game".

"I've had a lot of people come in and just be very friendly, very curious, very interested, watching me and saying 'wait, you can't see and you're better than I am at this'.

"So that's always a fun compliment to have paid, regardless of how true or not it may be," he says.

As well as building up a following, he's become an advocate for gamers without sight, working with the RNIB (Royal National Institute of Blind People), and he also provides advice to developers on ways to make their titles more accessible.

Sightless Kombat has been streaming his progress in God of War Ragnarök

Since SK first got into gaming - "pressing buttons at random and nosediving planes" - he says there's been a lot of progress in the industry, but there's still work to do.

One problem he often sees is accessibility features implemented in one area of a game, but not in another, and that's somewhere he'd like to see improvements.

He says a good example is a failure to combine menu narration - where a voice reads out text in settings screens - and navigation assist, where the game will automatically guide your character through a level.

Without menu narration, SK needs assistance from a sighted person to set it up, and without navigation assist, it's hard to progress.

"So those two almost go hand in hand in a way that a lot of people might not think of initially," he says.

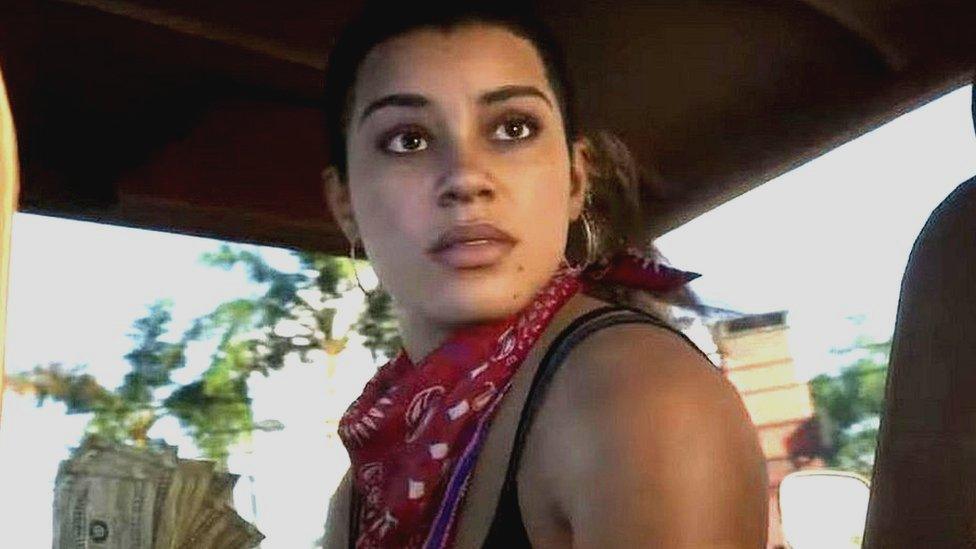

Getting people to think about accessibility is Cari Watterton's job.

She's the senior accessibility designer at Rebellion - the UK studio behind the popular Sniper Elite and Evil Genius series.

Cari and SK have been working together on a prototype called Project BlackKat - a stealth game that replaces a visual radar with "auditory vision cones" that reveal an enemy's location through sound.

But Cari's role is also about catering to the "massive spectrum of capabilities" in the world, which includes everything from motor impairments to cognitive issues.

Cari Watterton, from developer Rebellion, is in charge of making the studio's games as accessible as possible

Both her and SK agree the industry's approach to accessibility is inconsistent, and one of the big misconceptions is that it costs a lot to implement.

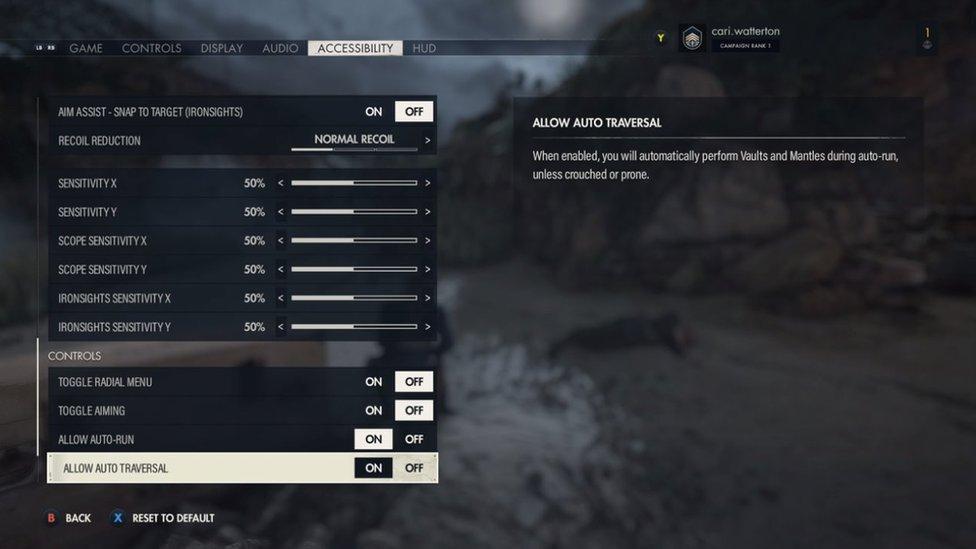

Cari says this doesn't have to be the case, and she was able to get two "high-impact" features into Rebellion's Sniper Elite 5 when she joined the studio a month before its release.

Despite limited time and budget, she says the game launched with automatic forward movement and automatic traversal - interactions that usually require holding down buttons for extended periods.

Cari says this can make make a big difference for people with dexterity issues.

"The fact we were able to get that in and have people be able to come in and have more energy saved for the actual sniping side of the game was fantastic," she says.

Cari says other tweaks, like making sure visual feedback is always paired with audio feedback, can be relatively cheap to do, especially if accessibility is baked into the development process from the start.

She says the other misconception is "people thinking that they need to do everything at once", but says it's a case of developers "working step by step" within the limits of what they can achieve.

"Even putting the smallest thing in, even if it's super late in the process, it helps and it's a step forward," she says.

Sniper Elite 5 has a dedicated accessibility menu allowing players to tweak options according to their needs

Accessibility is a hot topic in gaming at the moment.

The upcoming Game Awards has a category dedicated to it, gaming giant Electronic Arts recently opened up some of its development tools to other companies, and Sony has just capped things off by releasing its adaptive controller for disabled gamers.

But sites like Game Accessibility Nexus, external and Can I Play That?, external - which review games based on their assistance features - often find big releases lacking.

Cari admits "there are big goals and there are big things that are going to take more time", but says 2023 has been a "really, really good year for accessibility" in the industry.

She says there have been more games to celebrate this year, and more studios are recruiting into accessibility roles - and she hopes there will be more roles for people with lived experience of disability.

For her, for now, it's one of the best jobs in gaming.

"Seeing it reach more people, seeing it reach a wider audience, hearing people being like 'thank you so much for putting this in here, I can play this now'.

"It's so rewarding, because you don't want anybody to be left out," she says.

SK is also optimistic about the future.

"It helps far more people than most would actually think is even possible in terms of having accessibility features in a game," he says.

"Everybody should be able to play, whatever your your situation is, because when everybody plays, we all win.

"So get your accessibility consultants involved worldwide, get people testing your game from all walks of life with all sorts of challenges, and you will find barriers that need to be sorted out.

"And as you sort those things out, you'll be helping so so many people in your wider audience, you may not even know it."

- Published6 December 2023

- Published5 December 2023

- Published1 December 2023

- Published20 November 2023

- Published19 October 2023

- Published15 October 2023