Space is the final frontier for evolution, study claims

- Published

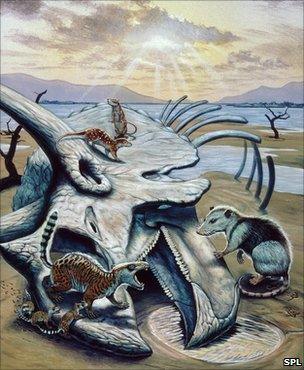

Mammals had plenty of space in which to thrive after the extinction of the dinosaurs

Charles Darwin may have been wrong when he argued that competition was the major driving force of evolution.

He imagined a world in which organisms battled for supremacy and only the fittest survived.

But new research identifies the availability of "living space", rather than competition, as being of key importance for evolution.

Findings question the old adage of "nature red in tooth and claw".

The study conducted by PhD student Sarda Sahney and colleagues at the University of Bristol is published in Biology Letters.

The research team used fossils to study evolutionary patterns over 400 million years of history.

Focusing on land animals - amphibians, reptiles, mammals and birds - the scientists showed that the amount of biodiversity closely matched the availability of "living space" through time.

Living space - more formally known as the "ecological niche concept" by biologists - refers to the particular requirements of an organism to thrive. It includes factors like the availability of food and a favourable habitat.

'Lucky break'

The new study proposes that really big evolutionary changes happen when animals move into empty areas of living space, not occupied by other animals.

For example, when birds evolved the ability to fly, that opened up a vast range of new possibilities not available to other animals. Suddenly the skies were quite literally the limit, triggering a new evolutionary burst.

Similarly, the extinction of the dinosaurs left areas of living space wide open, giving mammals their lucky break.

This concept challenges the idea that intense competition for resources in overcrowded habitats is the major driving force of evolution.

Professor Mike Benton, a co-author on the study, explained that "competition did not play a big role in the overall pattern of evolution".

"For example, even though mammals lived beside dinosaurs for 60 million years, they were not able to out-compete the dominant reptiles. But when the dinosaurs went extinct, mammals quickly filled the empty niches they left and today mammals dominate the land," he told BBC News.

Alternative view

However, Professor Stephen Stearns, an evolutionary biologist at Yale University, US, told BBC News he "found the patterns interesting, but the interpretation problematic".

He explained: "To give one example, if the reptiles had not been competitively superior to the mammals during the Mesozoic (era), then why did the mammals only expand after the large reptiles went extinct at the end of the Mesozoic?"

"And in general, what is the impetus to occupy new portions of ecological space if not to avoid competition with the species in the space already occupied?"