Manned flight around Moon considered

- Published

It was on the Apollo 8 mission that the famous "Earthrise" image was acquired

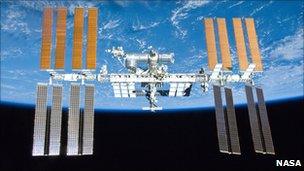

The possibility of using the space station as a launching point to fly a manned mission around the Moon is to be studied by the station partners.

Letters discussing the concept have been exchanged between the Russian, European and US space agencies.

The Moon flight would be reminiscent of the 1968 Apollo 8 mission which snapped the famous "Earthrise" photograph.

The agencies want the station to become more than just a high-flying platform for doing experiments in microgravity.

They would like also to see it become a testbed for the technologies and techniques that will be needed by humans when they push out beyond low-Earth orbit to explore destinations such as asteroids and Mars.

Using the station as the spaceport, or base-camp, from where the astronauts set off on their journey is part of the new philosophy being considered.

"We need the courage of starting a new era," Europe's director of human spaceflight, Simonetta Di Pippo, told BBC News.

"The idea is to ascend to the space station the various elements of the mission, and then try to assemble the spacecraft at the ISS, and go from the orbit of the space station to the Moon.

"What we are thinking about right now - but again we need more technical work to address this - [is] it should be a small spacecraft that goes around the Moon."

This vehicle would then likely return straight to Earth, rather than returning to the ISS.

Earth departure

Frank Borman, James Lovell and William Anders made history when they undertook the first lunar mission, testing the Command/Service Module (CSM) and its life-support systems in preparation for the later Apollo 11 landing. Their craft actually made 10 orbits of the Moon before returning home.

Just as with Apollo, any modern venture would need some kind of CSM element for the astronauts, together with a departure stage - a propulsion unit that could accelerate the astronauts' vehicle out of low-Earth orbit, putting it on a path to the Moon.

The new study will assess what precise elements are needed, and how many can be adapted from the spacecraft systems already in existence.

It should be stressed, however, that the idea is just that at the moment - an idea. It is a long way from becoming reality; just because the concept is being examined does not guarantee it will fly.

It should be noted also that the agencies, their industrial partners and a number of "space tourism" advocates have all previously thought about repeating the Apollo 8 Moon mission, if only to do one simple loop around the back.

What may be different this time is the new thinking about how the ISS should be exploited in the coming years.

All five station partners - the US, Russia, Europe, Japan and Canada - have indicated their desire to keep flying the platform until at least 2020. And engineers believe many of its modules will be serviceable even in the late 2020s.

Earth-orientated sciences in a zero-g environment will always be its priority, and with six individuals living permanently on the station the amount of astronaut time dedicated to experimentation has now been raised to something like 70 hours a week.

But with many laboratory tasks being automated, there should also be scope to begin new activities, and the partners believe one key role for the ISS going forward will be as a development platform for deep space exploration.

Can the ISS be used as a stepping stone to go beyond low-Earth orbit?

These activities could include demonstrations of new robots, inflatable modules in which to live or grow food ("greenhouses"), new life-support technologies, radiation protection systems, communications and sensor technologies, novel telemedicine approaches - anything that would be needed by astronauts on a self-sufficient mission far from Earth.

Learning how to assemble exploration vehicles at the ISS would also be part of this new vision.

If humans ever do go to asteroids or Mars, the scale of the infrastructure needed to complete a safe round trip could not possibly be launched on a single rocket from Earth. It will have to be sent up on multiple flights and joined together in orbit.

Doing this assembly at the ISS means it can be overseen by astronauts with ready access to tools if needed.

And if the crew assigned to man the deep-space mission travels up separately to the station, it would also mean all the elements for their long-duration flight could be launched without the complications of ultra-safe abort systems that complicate manned rockets.

The crew could instead ride to orbit in a simple, tried and tested rocket, such as a Soyuz, and then transfer across to their deep-space vehicle already waiting for them at the ISS.

- Published16 September 2010

- Published13 August 2010

- Published14 June 2010