Nuclear waste plans hang on trust

- Published

Sellafield - will the heart of the nuclear industry also be its final resting place?

The key to disposing of high-level nuclear waste appears to be not technology, or terrain - but trust.

In Eurajoki in Finland, where the local council decided seven years ago that it would like to see the waste from the country's nuclear reactors buried in its backyard, the T-word is everywhere, nestling alongside its spiritual siblings openness, honesty and transparency.

"We have had confidence on the operation of nuclear power, we have seen the safety culture," says Altti Lucander, a member of Eurajoki council at the time of that crucial vote in 2003.

"The basis for the people to accept something is that they must have confidence that everything is done honestly, open to the public."

In the UK, it is doubtful whether the image of nuclear power is quite as glossy.

This is an industry that - for all the electricity it has generated, for all the people it has trained and employed, for all the carbon emissions its operation has saved - has at various times used civilian reactors to make plutonium for weapons, sent barrels of radioactive waste to the ocean floor, sought to cover up leaks and accidents, and cost the taxpayer billions of pounds in overruns and cleanup operations and corporate collapses.

Now, the industry and the government are asking for trust once more. Specifically, they are asking for communities around the UK to volunteer to host the country's high-level waste, in the ground beneath their feet.

Presuming consent?

Asking people to have the stuff proved a workable strategy at Eurajoki, and at Forsmark in Sweden; in fact, in both countries several communities volunteered, leading to a kind of contest between rival bidders.

Given the UK's rather less comfortable nuclear history, you might presume that "not in my backyard!" would be the general answer here.

Altti Lucander: trust is a key commodity

And you would be right; only one community has so far said it might be interested.

Unsurprisingly, given its history as the national testbed of a pioneering nuclear nation, that place is West Cumbria - specifically, Copeland Borough Council (which includes Sellafield), neighbouring Allerdale Borough Council, and Cumbria County Council, which encompasses both of the others.

They have formed an alliance called the West Cumbria Managing Radioactive Waste Safely (WCMRWS) Partnership, whose key remit is to advise the councils as they decide whether to move to the next phase - entering formal discussions with the government and its agency, the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority.

"It is a unique experiment in the UK in governance - normally we're told what to do by the centre and not given much option, and this is the opposite of that," says Cumbria councillor and partnership chairman Tim Knowles, a former senior manager with British Nuclear Fuels Ltd (BNFL).

"The benefits of moving forward to develop a repository - and that's a long way away, many years, and a lot of decisions to be made before that happens if it happens - the benefits would clearly be in financial and employment terms. I wouldn't give a list because that would just be guesswork on my part, but the area wouldn't do it for nothing."

On the Eurajoki wish-list, intriguingly, was a new nuclear reactor. In fact, it is going to get two.

Command failure

The historical contrast between the UK and Finland is as stark as can be.

While the UK debated and hid and ignored its waste problem, while ownership of reactors went from public to private and back again at huge impact to the public purse, Finland quietly set up a fund to pay for disposal of its waste, located a site, and began digging.

Twenty years ago, while the now defunct Nuclear Industry Radioactive Waste Executive (Nirex) was telling people where it was going to site its repository (within spitting distance of Sellafield, rather conveniently), its Finnish counterparts were asking communities whether they might like to host the facility.

For Nirex - and now for the proposed US repository at Yucca Mountain - the centralised, directed approach ended in failure.

"It was an approach that was very common in the 80s and 90s - a lot of countries went down the same road - it's the 'decide, announce and defend' approach," says Barbara Pastina, a nuclear engineer who has worked on repositories in the US and now in Finland.

"In a repository programme there are technical challenges; but the societal challenges are at least in my mind much bigger."

Tunnel opening

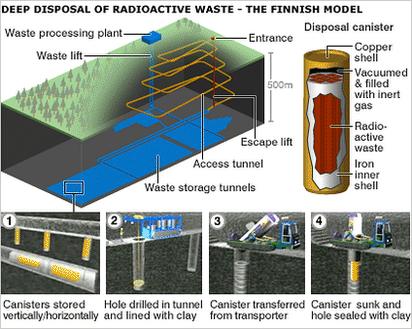

The result of Finnish authorities not deciding, announcing and defending is the Onkalo facility - a tunnel that spirals down into the ground, with the bottom levels now more than 400 metres under the surface

The waste itself would be stored at about this depth, so long as the rock turns out to be as stable and dry as the geologists think it is.

Unlike the UK, Finland does not re-process spent fuel. Instead the rods will be placed intact into steel canisters inside a copper casing.

Each canister will nestle inside a bed of bentonite clay, intended to protect it against any water that should trickle through the rock, and against movements of the rock itself.

These could be quite major, given that another Ice Age is likely to materialise well before the fuel rods' radioactivity has quietened to near background levels.

None of this would be happening, however, without the trust of those above ground.

Backyard bonuses

Back in Cumbria, the WCMRWS Partnership has sent early feelers out into the community; and for proponents of the repository, the results are not entirely discouraging.

Just over half of the people surveyed knew something about the proposal. And half are already in favour of pursuing talks, with a quarter opposed.

If those numbers persist, having the waste in their backyard seems a possibility.

Among those lined up against the scheme is Martin Forwood, a long-time campaigner with the organisation Cumbrians Opposed to a Radioactive Environment (Core).

"Firstly it's a very unfair thing now to ask a community to volunteer simply because the industry has been producing waste for 50 years with little thought for its after-management," he says.

"And now, because they're getting in a pickle - they've got too much waste, they don't know what to do with it - they want to offload it onto the general public with some bribery from government.

"I don't think, quite honestly, from the evidence of past efforts like this, that public opinion carries very much weight at all; if they want to have this nuclear dump, they'll press ahead with it whatever public opinion is."

Which brings us back to trust…

Hole truth

The problem confronting everyone who looks at the problem is this: if you do not select a site, build a repository and put the waste in it, then you are signing up to keeping the stuff above ground in warehouses for tens of thousands of years, with all the costs and risks that bequeaths to future generations, until and unless some new magical technology comes along that can lick it into safer shape.

Most of the UK's high-level waste is currently stored at Sellafield - and without a repository, it will remain

That is why the government wants a repository.

But even if West Cumbria goes ahead, the first consignments of waste would not be sent down the shaft until about 2040.

Having built the first commercial-scale nuclear power station in the world, the UK looks like being one of the last nuclear countries in the world to implement a lasting solution for the waste.

Without a greater degree of trust than currently pertains, however - without a willingness to say "yes, in my backyard" - the repository might not happen at all.

If Copeland and Allerdale decide not to enter talks - a decision due next year - the country will effectively not have a strategy for disposing of its most dangerous waste.

When asked, the government's only declared Plan B, inherited from its Labour predecessors, is to make Plan A work. If there proves not to be enough trust, one might ask - how can it work?

Richard.Black-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk

You can hear more about the UK's nuclear waste disposal plans - how they were drawn up, and where the waste comes from - in Nuclear Waste - Not In My Backyard, on BBC Radio Four at 2000 BST on Tuesday

- Published7 July 2010